When you picture the Earth’s landscapes, what comes to mind? Perhaps the jagged peaks of the Himalayas, the sprawling Grand Canyon, or the rolling hills of Tuscany. We are drawn to topography, to the dramatic rise and fall of the land. Yet, the most common landscape on our planet is one that almost no human has ever seen, a place defined by its almost perfect, featureless expanse: the abyssal plain.

Stretching across more than 50% of the Earth’s surface, these vast, dark plains are, quite simply, the flattest places on the planet. They are the true face of our world, hidden beneath miles of water.

What Are Abyssal Plains?

Abyssal plains are immense, flat, sediment-covered areas of the deep ocean floor. They are typically found at depths between 3,000 and 6,000 meters (about 10,000 to 20,000 feet), nestled between the continental rise and the mid-ocean ridges. If you could drain the oceans, you would find these plains dominating the globe, making continents and mountain ranges look like mere islands and wrinkles in a vast, smooth landscape.

Their scale is difficult to comprehend. The Sohm Abyssal Plain in the North Atlantic, for example, covers an area of about 900,000 square kilometers (350,000 square miles)—larger than France and Spain combined. And it’s just one of many. These are not small, isolated features; they are the fundamental bedrock of the deep sea.

The Making of a Perfectly Flat World

The incredible flatness of abyssal plains is not how the seafloor starts out. The oceanic crust is actually born in fire and violence at mid-ocean ridges, creating a rugged, mountainous terrain of volcanic rock. So, how does this jagged landscape get transformed into something as level as a tabletop?

The answer lies in a slow, patient, and relentless process: the rain of sediment.

The Never-Ending Snowfall

For millions of years, a fine “snow” of particles has been drifting down from the sunlit waters above, blanketing the seafloor. This sediment comes from two main sources:

- Biogenous Ooze: This is the primary component. It consists of the microscopic shells and skeletons of countless marine organisms like plankton—foraminifera, diatoms, and coccolithophores. When these tiny creatures die in the upper ocean, their durable remains sink, accumulating on the bottom in thick layers of what is called “ooze.”

- Terrigenous Sediment: This includes fine-grained clays and silts that are washed from the continents by rivers, blown out to sea as dust, or carried by icebergs. This terrestrial dust travels thousands of miles before finally settling in the deep.

Over eons, this continuous rain of sediment, often accumulating at a rate of only a few centimeters per thousand years, acts like a thick blanket of freshly fallen snow. It buries the rugged volcanic topography, filling in the deepest valleys and smoothing over the jagged peaks until all that remains is a vast, uniform plain.

Underwater Avalanches

While the slow rain of sediment is the primary architect of flatness, another, more dramatic force is also at play: turbidity currents. These are powerful, fast-moving underwater avalanches of sediment, sand, and mud. Triggered by earthquakes or simple instability on the continental slope, they race down into the deep, carrying enormous loads of material. When these currents reach the abyssal plain, they slow down and spread out, depositing their sediment in broad, flat layers known as turbidites. A single turbidity current can lay down a thick layer of sediment over a massive area in just a few days, contributing significantly to the smoothing process.

Life in the Perpetual Night

The environment of an abyssal plain is one of the most extreme on Earth. There is:

- Total Darkness: Sunlight cannot penetrate these depths, meaning there is no photosynthesis.

- Crushing Pressure: The pressure can exceed 600 times that at sea level—equivalent to having a bus balanced on your thumb.

- Frigid Cold: Water temperatures hover just above freezing, typically between 0-4°C (32-39°F).

Given these conditions, you might expect the abyssal plains to be lifeless deserts. But while life is sparse, it is certainly not absent. The creatures that call this place home are masters of survival, adapted to a world of scarcity and pressure.

A World Fed by Crumbs

With no primary production, life in the abyss depends entirely on the “marine snow” that drifts down from above. This organic material is the base of the food web. Detritivores, or “waste-eaters”, crawl across the seafloor, consuming the nutrient-rich mud. Think of sea cucumbers as the earthworms of the deep, tirelessly processing sediment. They are joined by brittle stars, sea pigs, and various worms.

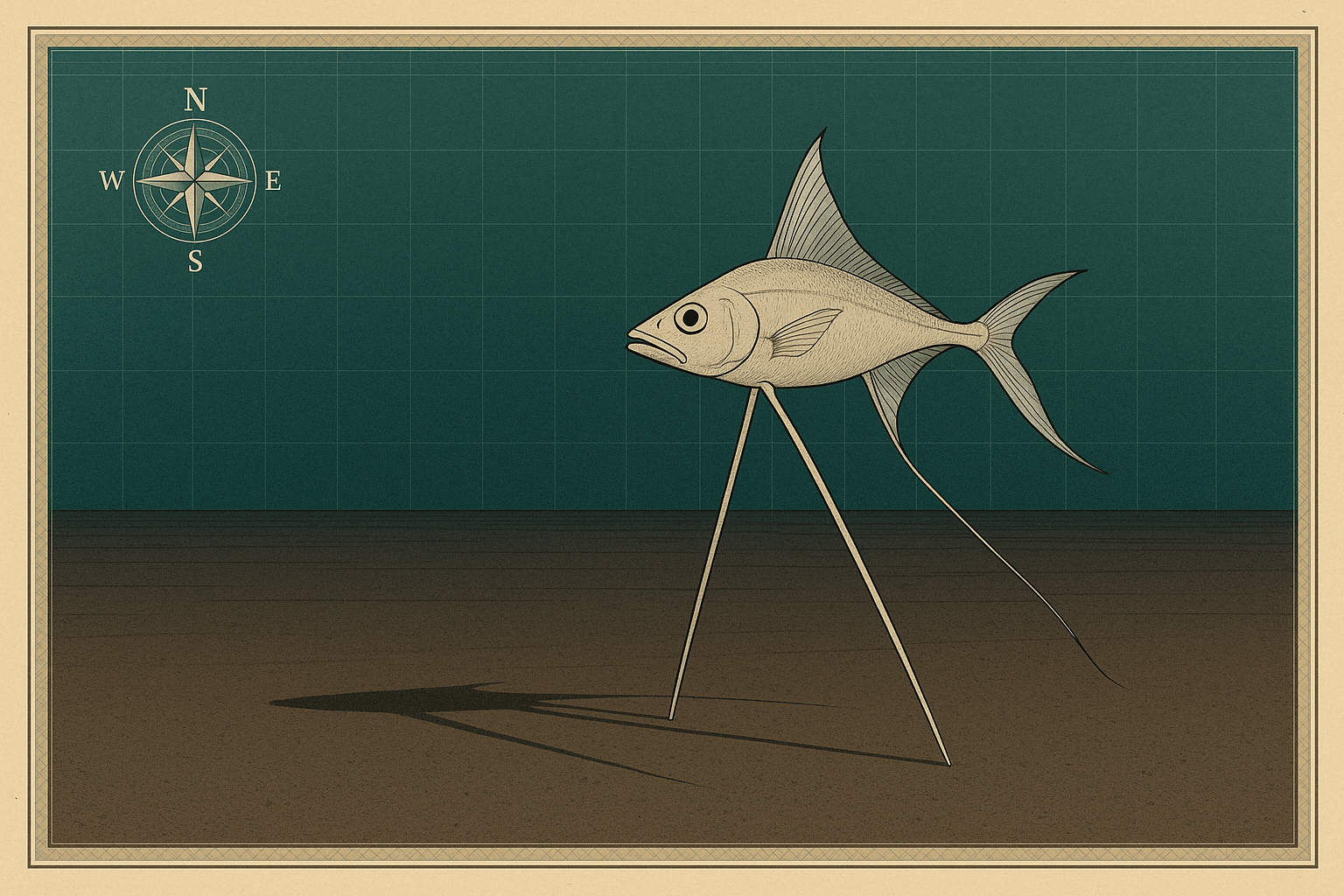

Life here is slow. With a limited food supply, animals have incredibly slow metabolisms to conserve energy. Fish like the tripod fish have adapted by perching on the seafloor on long, stilt-like fins, waiting patiently for a tiny crustacean to drift by.

Occasionally, a feast arrives. When a large animal like a whale dies in the upper ocean, its carcass can sink to the bottom. This “whale fall” becomes an oasis of life, providing a massive, concentrated source of food that can support a unique and complex ecosystem of scavengers—from sleeper sharks and hagfish to bone-eating “zombie worms”—for decades.

Our Connection to the Deep

For most of human history, the abyssal plains were a complete mystery. Today, thanks to sonar mapping, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and deep-sea submersibles, we are beginning to peel back the darkness and understand their significance.

These plains are not just empty spaces; they are critical to the health of our planet. The sediments act as a massive carbon sink, locking away carbon from the atmosphere for millions of years and playing a vital role in regulating global climate. They also hold vast, untapped reserves of minerals in the form of polymetallic nodules—potato-sized lumps of manganese, nickel, cobalt, and copper that have precipitated out of the seawater over eons. This has made the abyssal plains a new frontier for deep-sea mining, raising profound questions about how to balance resource extraction with the preservation of these unique, fragile ecosystems.

We have explored more of the surface of Mars than we have of our own planet’s abyssal plains. They represent the largest single habitat on Earth, yet we know less than 0.05% of it in any detail. As we continue to send our robotic eyes into the deep, we are sure to uncover more secrets from this dark, silent, and incredibly flat world that dominates our planet.