Look up at the skyline of any major metropolis—New York, Chicago, London—and you’ll see a forest of steel and glass. Some towers rise straight and true, while others seem to defy physics, leaning out over their shorter neighbors in a stunning display of architectural acrobatics. This urban ballet isn’t just clever engineering; it’s the physical manifestation of an invisible, high-stakes real estate market. Welcome to the world of air rights, where developers don’t just buy land, they buy the sky.

What Exactly Are Air Rights?

The concept of owning the space above your land is rooted in an ancient legal principle: “Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos”, a Latin phrase meaning, “Whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to Heaven and down to Hell.” For centuries, this defined property ownership in two dimensions. But in the crowded vertical landscape of a modern city, owning a slice of heaven has become a bit more complicated—and a lot more valuable.

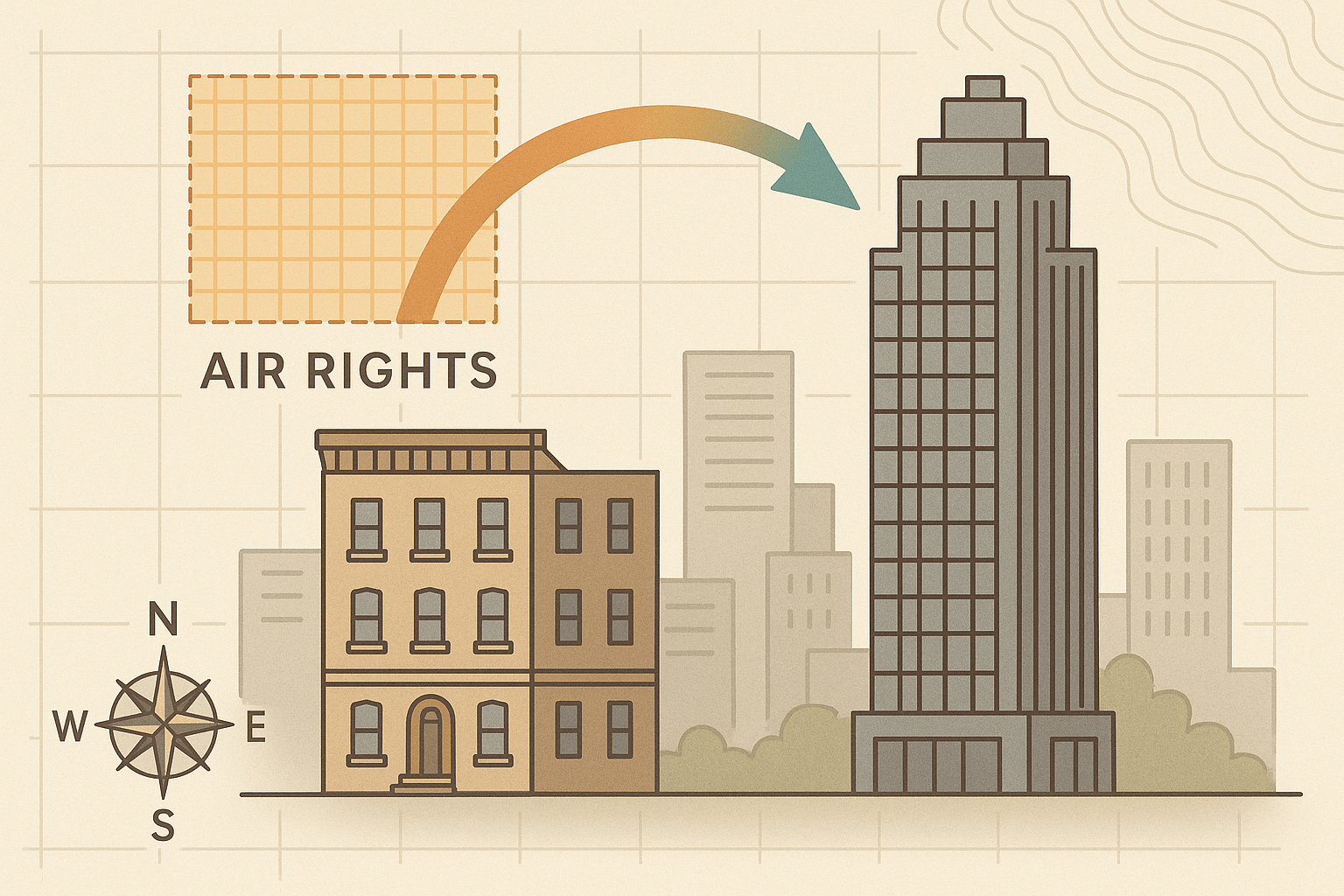

Today, air rights (also known in planning circles as Transferable Development Rights or TDRs) represent the unused development potential of a piece of property. Think of it as a development “budget” assigned to every plot of land by the city. If a building doesn’t use its full budget, it can sell the leftover potential to someone else. This isn’t just empty space; it’s a quantifiable, sellable asset that can be worth millions of dollars.

Zoning the Vertical City: The Role of FAR

To understand how this invisible market works, we need to talk about a key tool in human geography and urban planning: zoning. Cities create zoning codes to regulate what can be built where, controlling everything from a building’s use (commercial, residential) to its height and bulk.

The magic number that governs a building’s size is the Floor Area Ratio (FAR). It’s a simple but powerful formula:

FAR = Total Floor Area of a Building ÷ Total Area of the Lot

For example, imagine a 10,000-square-foot lot in a district with a FAR of 15. The developer has the right to build a structure with a total of 150,000 square feet of floor space (10,000 x 15). They could build a 15-story building covering the entire lot, or a 30-story building covering half of it.

Now, what if that same lot is occupied by a beautiful, historic three-story church with only 20,000 square feet of floor space? The church has 130,000 square feet (150,000 – 20,000) of unused, “buildable” area. These are its air rights, a phantom asset floating above its steeple. In a dense city, that unused space is a goldmine.

From Landmark to Skyscraper: A Tale of Two Lots

The transaction is a perfect symbiosis of urban needs. On one side, you have a “sending lot”—often a landmarked building, a theater, or a low-rise structure that cannot or does not wish to build any higher. These institutions are often cash-strapped and need funds for maintenance. On the other side is a “receiving lot”—a developer who wants to build a skyscraper taller and more profitable than their lot’s FAR allows. By purchasing the air rights from the landmark, the developer can add that square footage to their own project, allowing them to build higher and bigger. This transfer is typically limited to adjacent properties or within the same zoning district to prevent chaotic, unbalanced development.

Case Studies: Where the Sky is for Sale

Nowhere is the impact of air rights more visible than in New York City. The city’s 1961 Zoning Resolution pioneered the concept to encourage historic preservation. The most famous example is Grand Central Terminal. Facing demolition in the 1960s, the terminal’s owners instead sold its vast air rights, which helped fund its preservation and enabled the construction of neighboring skyscrapers, including the MetLife Building. More recently, the super-skinny supertalls of “Billionaires’ Row” south of Central Park, like 432 Park Avenue and Central Park Tower, were only made possible by assembling air rights from multiple smaller, adjacent buildings.

While New York is the epicenter, other cities have adopted similar systems. In Chicago, air rights transfers have allowed for the expansion of buildings along the Chicago River and helped preserve historic facades in the Loop. In London, a related but distinct concept known as “Rights of Light” guarantees long-standing buildings a reasonable level of natural light, forcing developers to design around their neighbors or negotiate multi-million-pound settlements to build in their “light space.”

Buildings That Reach Sideways: The Cantilever Effect

One of the most dramatic architectural consequences of the air rights market is the cantilever. When a developer buys air rights from an immediately adjacent, shorter building, they don’t just get to build taller—they can build over it. This is why you see so many new skyscrapers that start on a narrow base and then flare out dramatically several stories up.

Buildings like New York’s 111 West 57th Street or the gravity-defying 56 Leonard in Tribeca are prime examples. They literally occupy the airspace they purchased from their neighbors. This architectural maneuver is a direct geographical expression of a financial transaction, etching the invisible lines of property sales into the city skyline.

The Great Urban Debate: Progress or Problem?

The sale of the sky is not without controversy, sparking a heated debate about the future of urban density.

- The Pros: Proponents argue that air rights are a brilliant tool for smart growth. They provide a powerful financial incentive for historic preservation, saving beloved landmarks from the wrecking ball. They also allow cities to concentrate density in desired areas, such as near transit hubs, which can help combat suburban sprawl and create more walkable, efficient urban centers.

- The Cons: Critics, however, point to the downsides. The proliferation of supertall skyscrapers creates “concrete canyons” that cast long shadows, robbing public parks and smaller buildings of sunlight. There are also equity concerns; the immense profits are often concentrated in the hands of a few developers and wealthy property owners, while potentially making neighborhoods less affordable. Finally, some argue that it prioritizes financial engineering over thoughtful urban planning, leading to oddly shaped buildings and overwhelming density.

The Future of the Urban Sky

Air rights are an invisible but foundational force in the geography of our cities. They are a uniquely urban solution to the universal problem of limited space, turning empty air into a commodity that can save a historic church or birth a new skyscraper. As our world becomes increasingly urbanized and cities strive to house more people sustainably, the market for the sky will only become more important.

The next time you walk through a downtown core and crane your neck to see the top of a soaring tower, look at the smaller buildings at its base. You might just be looking at the foundation of a deal that allowed that skyscraper to reach for the clouds—a testament to the fact that in the modern city, even the sky has a price tag.