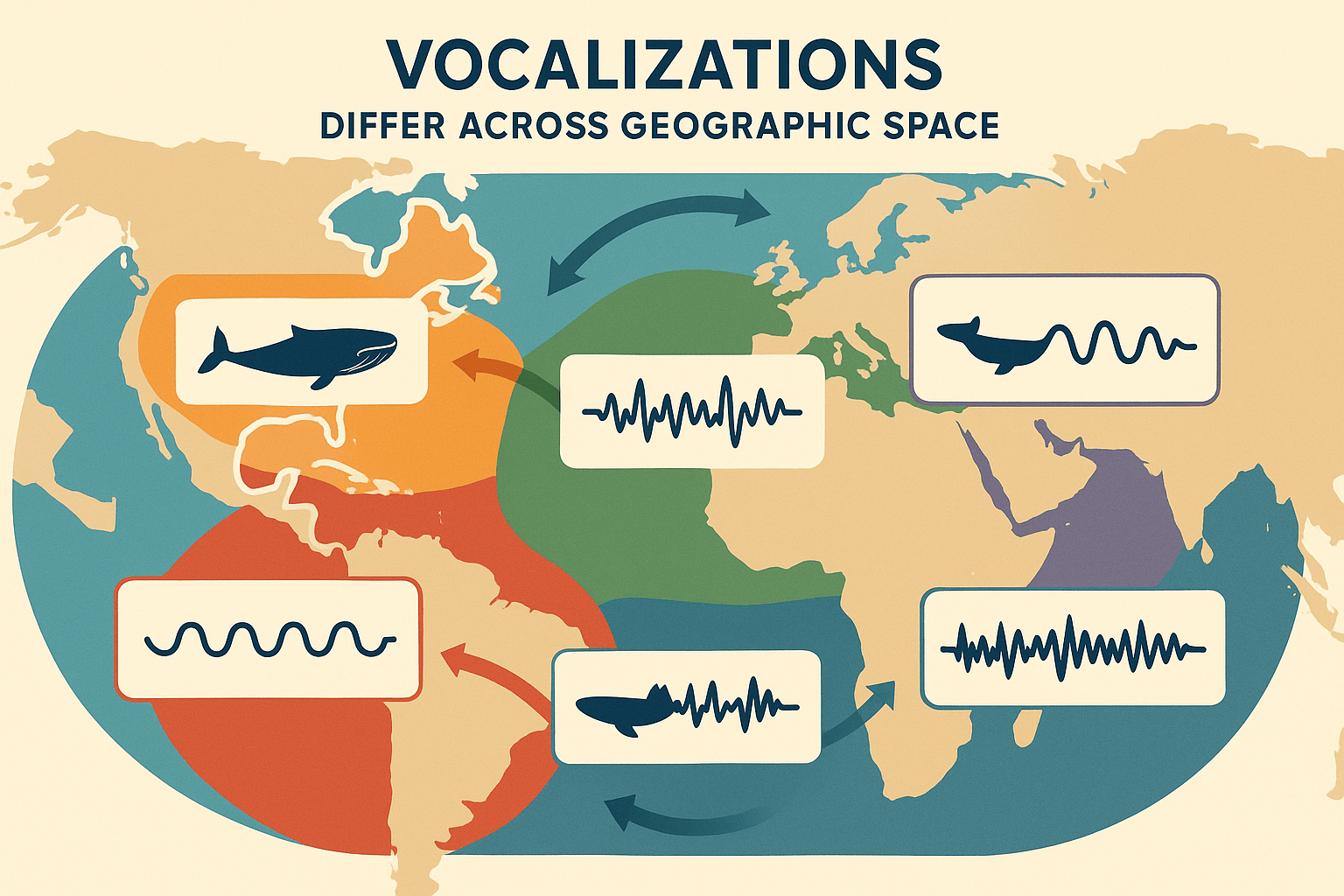

Bioacoustics is the study of how animals produce, receive, and interpret sound. And one of its most compelling discoveries is that many species, particularly those that learn their vocalizations, develop distinct “dialects.” Just as human languages evolve in isolated communities, animal calls can drift and change over generations when populations are separated. A physical barrier, no matter how small, can be the catalyst for a new acoustic culture.

The Ocean’s Echo Chambers: Whale Songs Across the Seas

The ocean is a perfect laboratory for bioacoustic geography. It’s a vast, connected environment, but it’s also partitioned by continents, temperature zones, and complex currents. For a species like the humpback whale, these partitions are everything.

Humpback males are famous for their complex, haunting songs, which are culturally transmitted—young males learn them from their elders. Astonishingly, all the males in a single breeding population, like those in the waters off Hawaii, will sing the same evolving song. But that song is completely different from the one being sung by humpbacks in the Caribbean Sea. The North Pacific and North Atlantic are, for a whale, two separate worlds. The continents of North and South America form an impassable barrier, creating two distinct bioacoustic regions.

Even within a single ocean, geography carves out dialects. The songs of humpbacks off the east coast of Australia are different from those off the west coast. Why? Because they belong to different breeding stocks that follow separate migration routes along the coastline, effectively behaving as separate cultural groups. The map of whale songs is a map of oceanography itself.

It’s not just humpbacks. Consider the orca, or killer whale, in the Salish Sea stretching from Seattle, USA, to Vancouver, Canada. Here, different pods have their own unique sets of calls, passed down through matriarchal lines. The “Southern Resident” orcas, which primarily eat Chinook salmon, have a dialect entirely different from the “Transient” (or Bigg’s) killer whales that roam the same waters but hunt marine mammals. Their dialects are tied to their social structure and foraging culture, which in turn are shaped by the geography of their food sources within this complex coastal ecosystem of islands and inlets.

A Chorus Divided: Birds on Different Sides of the Barrier

If oceans are grand stages for dialects, then terrestrial landscapes are mosaics of acoustic diversity. For birds, a barrier doesn’t need to be an ocean; a single mountain range or a dense, sprawling city is more than enough to create a new accent.

One of the most well-studied examples is the white-crowned sparrow of California. Ornithologists in the 1970s made a remarkable discovery around the San Francisco Bay Area. Sparrows in Marin County, just north of the Golden Gate Bridge, had a measurably different “song” than those in Berkeley, just across the bay. These birds can fly, but they tend to be non-migratory and stick to their local territories. Over time, the geographic separation created by the bay was enough to foster distinct dialects. A sparrow from Marin would sound like a foreigner to a sparrow from Berkeley.

This “vocal geography” scales up dramatically:

- Mountain Ranges: The Rocky Mountains in North America or the Andes in South America act as colossal dividers. Bird populations on the eastern slopes can have completely different calls from their counterparts on the western slopes, despite being the same species. For a small songbird, a 14,000-foot peak is as impassable as an ocean.

- Human Geography: Urbanization is creating new, artificial barriers. A vast city like Phoenix, Arizona, can become a “heat island” desert in the middle of a natural desert, isolating populations of cactus wrens in a way that didn’t exist a century ago. Researchers are now finding that the calls of wrens in one suburban patch are diverging from those in another, separated by highways and concrete.

Primate Parlance in Fragmented Forests

Primates, our closest relatives, also showcase a clear link between geography and vocalization. Their calls—used for warning of predators, defending territory, and maintaining social bonds—are highly susceptible to geographic influence.

In West Africa’s Taï National Park in Ivory Coast, researchers studying Campbell’s monkeys found that their alarm calls could vary subtly between groups separated by a major river. The river acts as a porous, but significant, barrier to social interaction, allowing communication styles to slowly diverge.

Perhaps the most powerful geographic force shaping primate dialects today is deforestation. This is a stark example of human geography’s impact. As rainforests in places like the Amazon Basin or Borneo are carved into smaller, isolated fragments, the primate populations within them become trapped. A group of gibbons in one forest patch can no longer interact with a group just a few kilometers away across a palm oil plantation. This forced isolation accelerates the formation of new dialects, creating a fragmented acoustic landscape that mirrors the fragmented physical one. Each forest patch becomes an island, and on each island, a unique vocal culture begins to form.

Mapping the Unseen World of Sound

When we look at a map, we see borders, mountains, and rivers. But bioacousticians are learning to hear a different kind of map overlaid on top of it—a map of sound. This acoustic map is essential for conservation. By listening to the dialects of a whale or bird population, scientists can track their movements, understand their social health, and identify distinct populations that need protection.

If a regional dialect vanishes, it means more than just a few quiet animals. It could signify the loss of an entire, genetically distinct population—a unique culture that was sculpted over millennia by the geography of our planet. The next time you’re outdoors, listen closely. The chirps, howls, and songs you hear aren’t just noise; they’re a declaration of identity, a story of an animal’s deep and unbreakable connection to its place on Earth.