The Last Great Wilderness

Before we delve into the politics, we must appreciate the physical geography that makes Antarctica so unique. It is a continent of superlatives. The Antarctic Ice Sheet, in places nearly three miles (4.8 km) thick, blankets almost 98% of the land. This immense weight depresses the continental bedrock, with some areas lying more than 1.5 miles (2.5 km) below sea level. Beneath this ice lie mountain ranges, like the Gamburtsev Mountains, which are as large as the European Alps but have never been seen by human eyes.

This extreme environment makes the continent a pristine natural laboratory. Ice cores drilled from deep within the sheet act as time capsules, providing an invaluable record of Earth’s climate history stretching back hundreds of thousands of years. The surrounding Southern Ocean is a unique and fragile ecosystem, teeming with life from microscopic krill to colossal blue whales.

A Race for the Bottom of the World

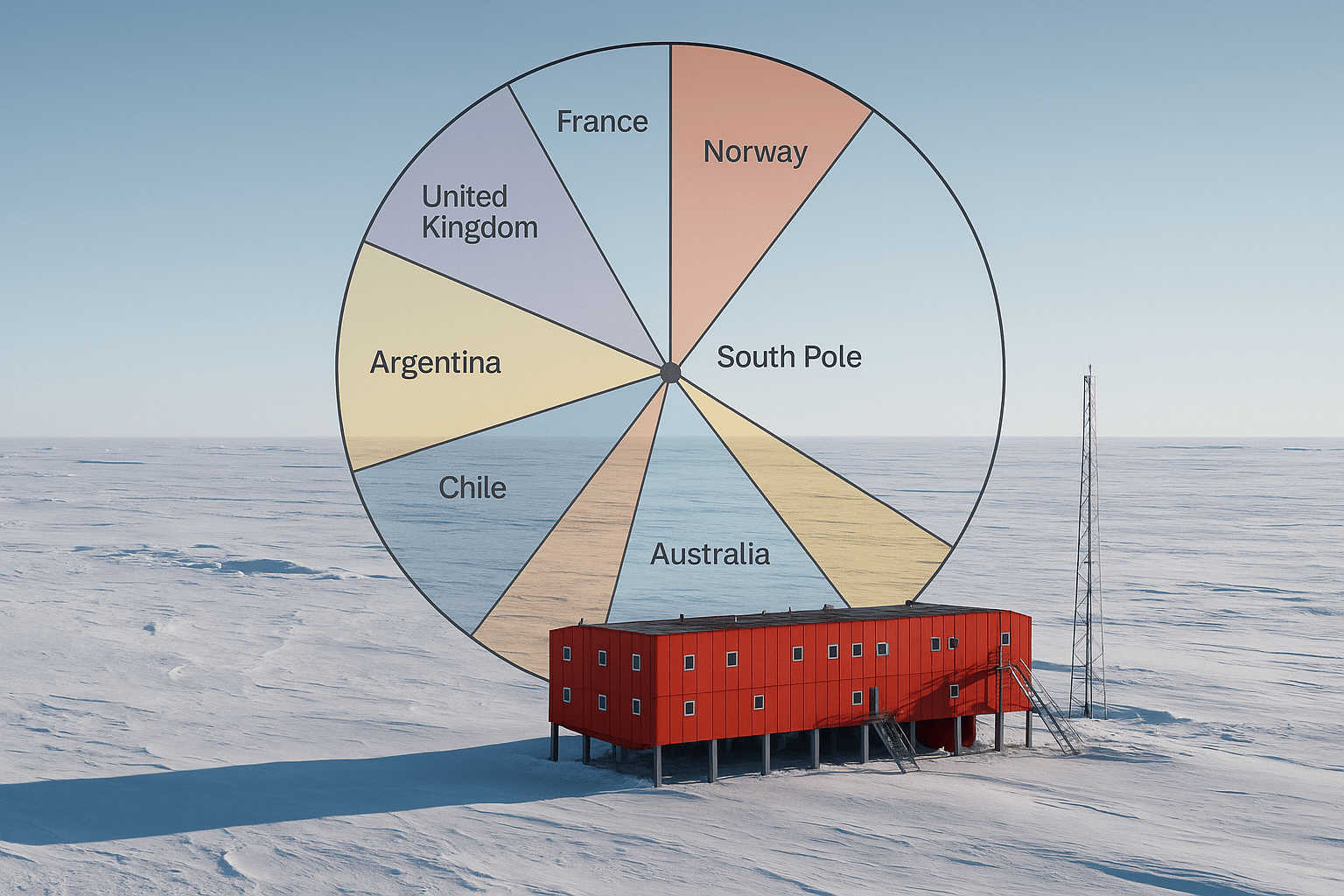

For centuries, Antarctica was Terra Australis Incognita—the unknown southern land. But as exploration ramped up in the early 20th century, so did national ambition. Nations began to stake claims, often in wedge-shaped sectors extending from the coast to the South Pole. This led to a messy and potentially explosive geopolitical map.

By the 1940s, seven nations had laid formal territorial claims:

- Argentina (25°W to 74°W)

- Australia (45°E to 136°E and 142°E to 160°E)

- Chile (53°W to 90°W)

- France (136°E to 142°E)

- New Zealand (150°W to 160°E)

- Norway (20°W to 45°E)

- United Kingdom (20°W to 80°W)

A quick look at the longitude lines reveals a major problem: the claims of the UK, Argentina, and Chile overlapped significantly, creating a hotbed of diplomatic tension in the world’s coldest place. Furthermore, global powers like the United States and the Soviet Union refused to recognize any of these claims, reserving their right to make claims of their own in the future.

A Diplomatic Deep Freeze: The Antarctic Treaty

Amidst the Cold War, the world came together for a remarkable act of foresight. The International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-58 saw unprecedented scientific collaboration in Antarctica. Building on this success, the 12 nations active on the continent at the time—the seven claimants plus Belgium, Japan, South Africa, the USA, and the USSR—negotiated the Antarctic Treaty, which was signed in 1959 and entered into force in 1961.

The treaty is a masterpiece of diplomacy, effectively putting the entire continent’s political status on ice. Its core principles are simple but profound:

- For Peace Only: Antarctica shall be used exclusively for peaceful purposes. All military measures, including weapons testing and military bases, are prohibited. It is the world’s largest demilitarized zone.

- Freedom of Science: The treaty guarantees the freedom of scientific investigation and promotes international cooperation to that end.

- Open Exchange: Scientific observations and results from Antarctica shall be exchanged and made freely available.

- The Diplomatic Freeze: This is the treaty’s genius, found in Article IV. It does not recognize, dispute, or establish territorial claims. No new claims can be made while the treaty is in force. In essence, it “freezes” the issue of sovereignty, allowing countries with conflicting claims to work alongside each other peacefully.

Today, the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) has grown to include 56 signatory nations, representing over 80% of the world’s population. It’s a testament to the idea that a place can be governed for science and peace, beyond the grasp of national ownership.

Science as Sovereignty: Life on the Ice

So, who lives in Antarctica? The answer is no one, permanently. The continent’s human geography is one of temporary residents—a rotating population of scientists and support staff from around 30 different countries, housed in over 70 research stations scattered across the ice.

These stations are the physical embodiment of a nation’s presence. In a land where military might and territorial markers are forbidden, a country’s influence is measured by its scientific footprint. The American McMurdo Station is the largest, a sprawling logistical hub that can feel like a small town. Russia’s Vostok Station, located near the Southern Pole of Cold, famously recorded the lowest natural temperature ever on Earth (-89.2 °C / -128.6 °F). China has rapidly expanded its presence, now operating five stations.

Operating a research station in Antarctica is a statement of commitment and a ticket to the decision-making table. The nations with “Consultative Party” status—those conducting substantial scientific research—are the ones who vote on the rules that govern the continent.

Cracks in the Ice? Rising Tensions

For over 60 years, the treaty has been a resounding success. But the 21st century is bringing new pressures that are testing its resilience.

The Lure of Resources

Geological surveys suggest Antarctica may hold significant deposits of oil, gas, and valuable minerals. A 1991 addition to the treaty, the Madrid Protocol, designated Antarctica as a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science” and banned all mineral resource activities. However, this protocol is up for review in 2048. As global resources dwindle and technology advances, the pressure to exploit the continent’s potential wealth may become immense.

A New Cold War?

Geopolitical maneuvering is on the rise. China’s growing investment is viewed by some as a long-term strategic play for future resource rights and influence. Russia has been accused of surveying for oil and gas reserves, potentially in violation of the spirit, if not the letter, of the protocol. Climate change is also a factor; as ice melts and access becomes easier, the continent becomes a more tangible prize in the great game of global power.

Life in the Southern Ocean

The waters surrounding Antarctica are not immune. The fishing industry, particularly for krill—a tiny crustacean vital to the entire Antarctic food web—is a multi-million dollar business. While regulated by a commission (CCAMLR), there are fears that expanding industrial fishing could destabilize the fragile ecosystem. A new frontier is “bioprospecting”, the search for unique microorganisms in Antarctica’s extreme environments that could be used for pharmaceuticals or industrial applications—a commercial activity the original treaty never envisioned.

A Continent at a Crossroads

Antarctica remains the greatest example of peaceful international governance on the planet. The treaty has preserved a continent for science, prevented conflict, and fostered collaboration among historic rivals. But it is not untouchable.

The coming decades will be a critical test. Will the spirit of 1959 prevail, or will the pressures of a resource-hungry, geopolitically competitive world finally crack the ice? The future of the last continent rests on our ability to continue choosing cooperation over conflict, and preservation over profit.