Imagine standing in a desert, the sun beating down on a vast, cracked-earth plain that stretches to the horizon. Now, picture massive, rusted fishing trawlers sitting stranded in the sand, their hulls listing like the skeletons of beached whales. This isn’t a surrealist painting; it’s the haunting reality of Moynaq in Uzbekistan, a former port city now dozens of kilometers from the nearest shore. This is the Aral Sea, or what’s left of it—a chilling monument to one of the most catastrophic man-made environmental disasters in history.

A Blue Jewel in the Central Asian Steppe

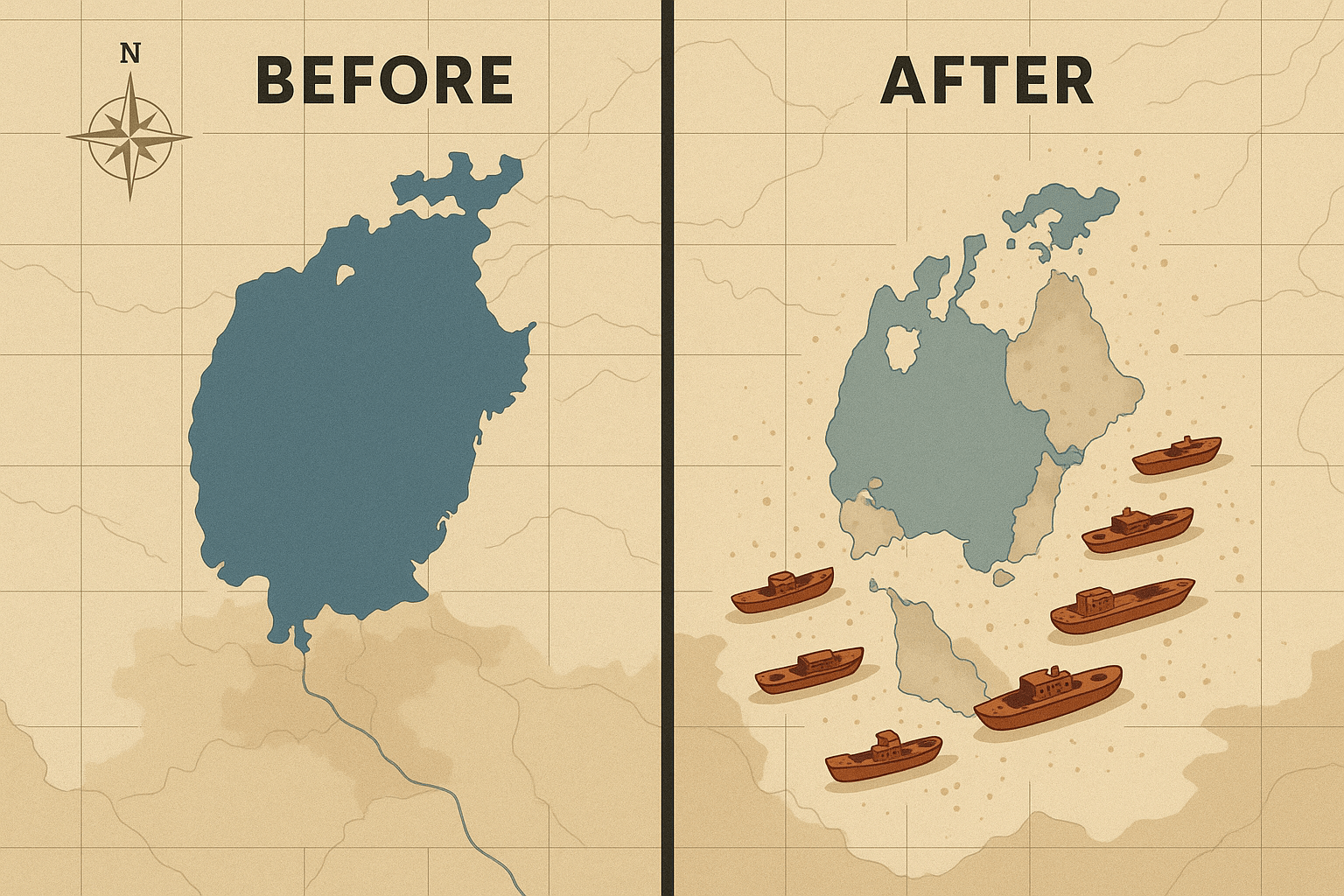

To understand the tragedy, we must first appreciate the sea that was. Until the mid-20th century, the Aral Sea was the fourth-largest inland body of water on Earth, a sprawling, slightly saline lake covering some 68,000 square kilometers. Nestled in the heart of Central Asia, it straddled the modern-day borders of Kazakhstan to the north and Uzbekistan to the south.

The Aral was a classic example of an endorheic basin—a closed geographical system with no outlet to the ocean. Its existence was a delicate balancing act, maintained by the inflow from two of Asia’s great rivers: the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. These rivers, born from the snowmelt of the distant Pamir and Tian Shan mountains, snaked across the arid steppes and deserts to replenish the sea, balancing the high rates of evaporation under the desert sun. For millennia, this equilibrium sustained a vibrant ecosystem, supporting a thriving fishing industry that produced a sixth of the Soviet Union’s entire fish catch.

Sowing the Seeds of Destruction

The fate of the Aral Sea was sealed not by a natural cataclysm, but by a geopolitical ambition. In the 1940s and 50s, Soviet planners in Moscow devised a monumental scheme to transform the Central Asian desert into a productive agricultural heartland. The goal was to achieve self-sufficiency in cotton, a crop dubbed “white gold”, alongside other water-intensive crops like rice and melons.

To realize this vision, the state orchestrated one of the most extensive water diversion projects ever undertaken. An immense network of unlined, leaky canals—including the colossal Karakum Canal in Turkmenistan—was dug to divert colossal volumes of water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. This water was siphoned off to irrigate millions of hectares of arid land.

The planners were not ignorant of the consequences; they were indifferent. In their calculus, the economic output of cotton and grain far outweighed the value of a “useless evaporator” like the Aral Sea. The sea was deemed a worthy sacrifice for the progress of the Soviet state. The lifeblood of the Aral was systematically choked off at its source.

The Vanishing Water: A Geographical Transformation

The impact was as swift as it was devastating. By the 1960s, the sea began to shrink noticeably. By 1987, the receding waters had become so shallow that the sea split into two separate bodies: the smaller North Aral Sea in Kazakhstan and the larger, crescent-shaped South Aral Sea in Uzbekistan. The decline accelerated. The South Aral itself later split into eastern and western lobes, with the eastern basin drying up completely by 2009.

In less than a human lifetime, the Aral Sea lost over 90% of its volume. A new, terrifying geographical feature was born on the exposed seabed: the Aralkum Desert. Covering over 60,000 square kilometers, it is the world’s youngest desert, a barren wasteland of salt and sand.

A Toxic Legacy: The Poisoned Land

The Aralkum is no ordinary desert. For decades, the rivers that fed the Aral Sea had carried not just water, but also a toxic slurry of agricultural runoff from the cotton fields. Pesticides (including DDT), herbicides, defoliants, and chemical fertilizers accumulated in the sea’s sediment. As the water evaporated, these toxins were left behind, concentrated in the dust and salt of the new desert.

Today, powerful dust storms whip across the exposed seabed, picking up millions of tons of this toxic salt-dust and carrying it for hundreds of kilometers. These “salt-sand storms” have contaminated surrounding farmland, destroyed pastures, and created a public health emergency for the half-million people living in the disaster zone.

The Human Cost: Ghost Ships and Broken Lives

The human geography of the region was shattered. Cities like Aralsk (Kazakhstan) and Moynaq (Uzbekistan) saw their identities and economies evaporate with the water. The fishing industry, which once employed over 40,000 people and supported a network of canneries, collapsed entirely. The iconic “ship graveyard” at Moynaq, where rusting trawlers lie marooned in the sand, is a powerful symbol of this economic death.

The health consequences have been dire. Local populations suffer from staggering rates of respiratory illnesses, esophageal and throat cancers, anemia, and kidney disease, directly linked to inhaling the toxic dust and drinking contaminated groundwater. Infant mortality rates in the region were once among the highest in the world.

A Changed Climate

The disappearance of such a massive body of water fundamentally altered the regional climate. The Aral Sea once acted as a climate moderator, softening the harsh continental climate. Without its regulating influence, winters have become colder and longer, and summers hotter and drier. The growing season has shortened, further crippling any remaining agricultural prospects and compounding the environmental catastrophe.

Can a Dead Sea Be Revived?

While the overall picture is bleak, there is a flicker of hope in the northern part of the old sea. In 2005, the government of Kazakhstan, with funding from the World Bank, completed the 13-kilometer-long Kokaral Dam. This structure was designed to separate the North Aral Sea from the terminally ill South Aral, concentrating the limited inflow from the Syr Darya into the smaller northern basin.

The results have been remarkable. The water level in the North Aral has risen by several meters, salinity has dropped significantly, and fish stocks have begun to rebound. The water, once 100 km away, is now just 25 km from the port of Aralsk, bringing with it the return of fishing and a fragile sense of optimism. The fate of the much larger South Aral Sea, however, remains grim; it is widely considered beyond saving.

A Lesson Etched in Salt and Dust

The story of the Aral Sea is more than a regional disaster; it is a global cautionary tale. It is a stark lesson in the law of unintended—or, in this case, ignored—consequences. It demonstrates with brutal clarity how quickly a vast ecosystem can be annihilated by large-scale, centrally planned projects that disregard the intricate connections of the natural world. The ships in the desert are a permanent warning, a geographical scar that reminds us of the profound and lasting price of sacrificing nature for human ambition.