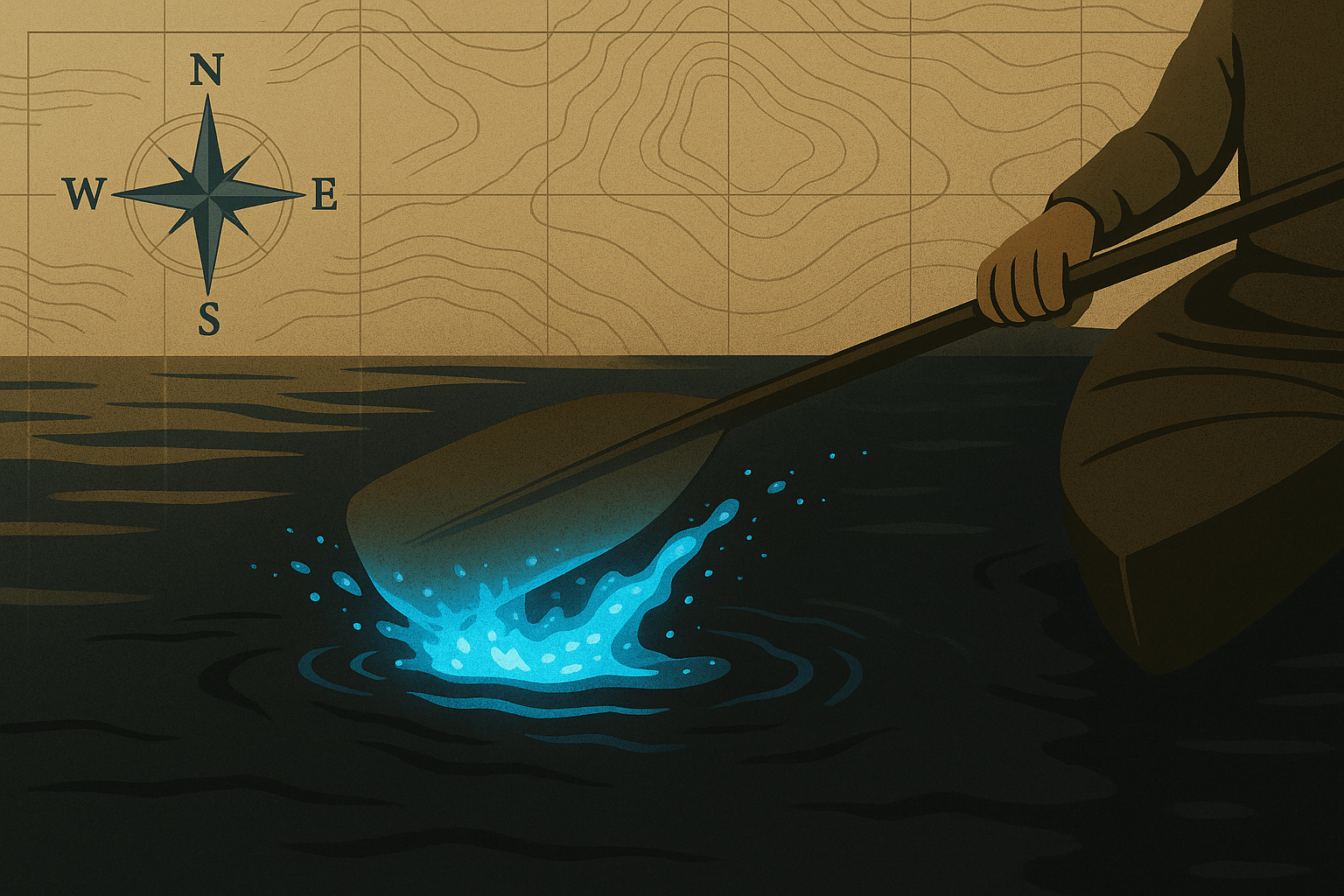

Imagine dipping a paddle into inky black water on a moonless night, only to see it erupt in a trail of shimmering, electric blue light. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the breathtaking reality of a bioluminescent bay. Scattered across the globe in a handful of precious locations, these “bio bays” are a testament to a perfect, fragile synergy between geography and biology, where the water itself comes alive with light.

At the heart of this mesmerizing phenomenon are microscopic, single-celled organisms called dinoflagellates. But for these tiny lifeforms to congregate in numbers dense enough to create a spectacle, they need a very specific stage. This is where geography becomes the director of the world’s most enchanting light show.

The Perfect Geographical Recipe

A true bioluminescent bay isn’t just any body of water that happens to have glowing plankton. It’s a rare ecosystem that requires a precise set of physical and environmental conditions to flourish. Think of it as a geographical recipe with several crucial ingredients.

Ingredient 1: A Sheltered Shape

The most important geographical feature of a bio bay is its shape. These bays are typically deep, but connected to the open ocean by a very narrow and often shallow channel, known in Spanish as a “boca” or mouth. This geography acts like a natural flask. The narrow opening limits the exchange of water with the sea, preventing the high concentration of dinoflagellates from being flushed out and dispersed by tides and currents. The calm, protected water inside the bay allows the organisms to thrive and multiply without disturbance.

Ingredient 2: The Mangrove Nursery

Look around the shoreline of the world’s brightest bio bays, and you will almost always find a dense forest of red mangroves. These trees are not just a scenic backdrop; they are a vital part of the ecological engine. The submerged roots of the red mangroves create a complex, sheltered habitat for countless marine species. More importantly for bioluminescence, as their leaves fall into the water and decay, they release tannins and, crucially, Vitamin B12. This particular vitamin is a superfood for the most common bioluminescent dinoflagellate, Pyrodinium bahamense, fueling its reproduction and allowing its population to reach the millions per gallon needed for a brilliant glow.

Ingredient 3: Warm, Salty, and Clear Waters

Dinoflagellates are sun-worshippers. They are a type of phytoplankton, meaning they photosynthesize to create energy. Therefore, they thrive in the warm, clear, tropical and subtropical waters found near the equator. Clear water allows sunlight to penetrate deep enough to power their photosynthesis during the day, charging them up for their light show at night. The high salinity of these bays also creates an environment where they can outcompete other types of plankton.

A Global Tour of Glowing Waters

While fleeting bioluminescence can be spotted in oceans all over the world, there are only five ecosystems consistently bright enough to be considered permanent bioluminescent bays. Geographically, they are clustered in the Caribbean, with a few notable cousins elsewhere.

Puerto Rico: The World Capital of Bioluminescence

The undisputed heartland of this phenomenon is the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, which is home to an astonishing three of the five permanent bays. This remarkable concentration speaks to the island’s ideal coastal geography.

- Mosquito Bay, Vieques: Officially certified by the Guinness World Records as the brightest bioluminescent bay in the world, Mosquito Bay is the gold standard. Located on the southern shore of the island of Vieques, its geography is textbook perfect: a narrow, curving channel, a deep basin, and a thick, pristine mangrove forest. Strict conservation efforts, including banning gas motors and swimming, have preserved its otherworldly glow.

- Laguna Grande, Fajardo: Located on the northeastern coast of the main island, this isn’t a true bay but a lagoon connected to the sea by a long, mangrove-lined canal. Kayaking through this dark, winding channel before emerging into the glowing lagoon is a truly magical experience.

- La Parguera, Lajas: Situated on the southwestern coast, La Parguera is the oldest-known bio bay in Puerto Rico. Its geography is slightly more open than the others, and it’s the only one that still permits motorboats and swimming, which has unfortunately diminished its glow compared to its protected counterparts.

Jamaica: The Luminous Lagoon

Near the port town of Falmouth on Jamaica’s north coast lies the Luminous Lagoon. Its unique geography is defined by the meeting of fresh water from the Martha Brae River and salt water from the Caribbean Sea. This brackish water creates a perfect nutrient trap, supporting an incredible density of dinoflagellates. Boat tours here offer visitors the chance to swim in the glowing water, their movements creating ethereal, glowing angel wings around them.

Vietnam: Ha Long Bay

While not a permanent “bio bay” in the same class as those in the Caribbean, Vietnam’s iconic Ha Long Bay is famous for its seasonal bioluminescence. Amidst the thousands of limestone karsts and isles, the sheltered waters can light up, particularly on dark nights with a new moon. The glow here is often more sporadic, but when conditions are right, kayaking or taking a night cruise can reveal shimmering trails of light in the wake of the boat.

The Human Geography: Tourism and Threats

The existence of these bays has profound implications for human geography. They are powerful economic drivers for the local communities in places like Vieques and Falmouth, creating jobs for tour guides, boat captains, and service industry workers. They are a source of immense local and national pride.

However, this very popularity poses the greatest threat. The delicate ecological balance is easily upset by human activity.

- Pollution: Chemical pollutants from sunscreen, insect repellent, and fuel runoff from motorboats can be toxic to dinoflagellates.

- Light Pollution: Increased coastal development brings artificial light, which diminishes the visibility of the natural glow and can disrupt the organisms’ circadian rhythms.

- Environmental Changes: Deforestation of the vital mangrove forests, dredging of channels, and the broader effects of climate change—like rising sea temperatures and increasingly powerful hurricanes—can permanently alter the bay’s chemistry and geography, extinguishing the light forever.

Witnessing a bioluminescent bay is to see geography, chemistry, and biology dance together in the dark. It is a powerful reminder of how intricate and fragile our planet’s ecosystems are. As travelers and custodians of the Earth, protecting these rare pockets of liquid light is a responsibility we must all share, ensuring that future generations can continue to dip their paddles into the water and watch the stars swim below.