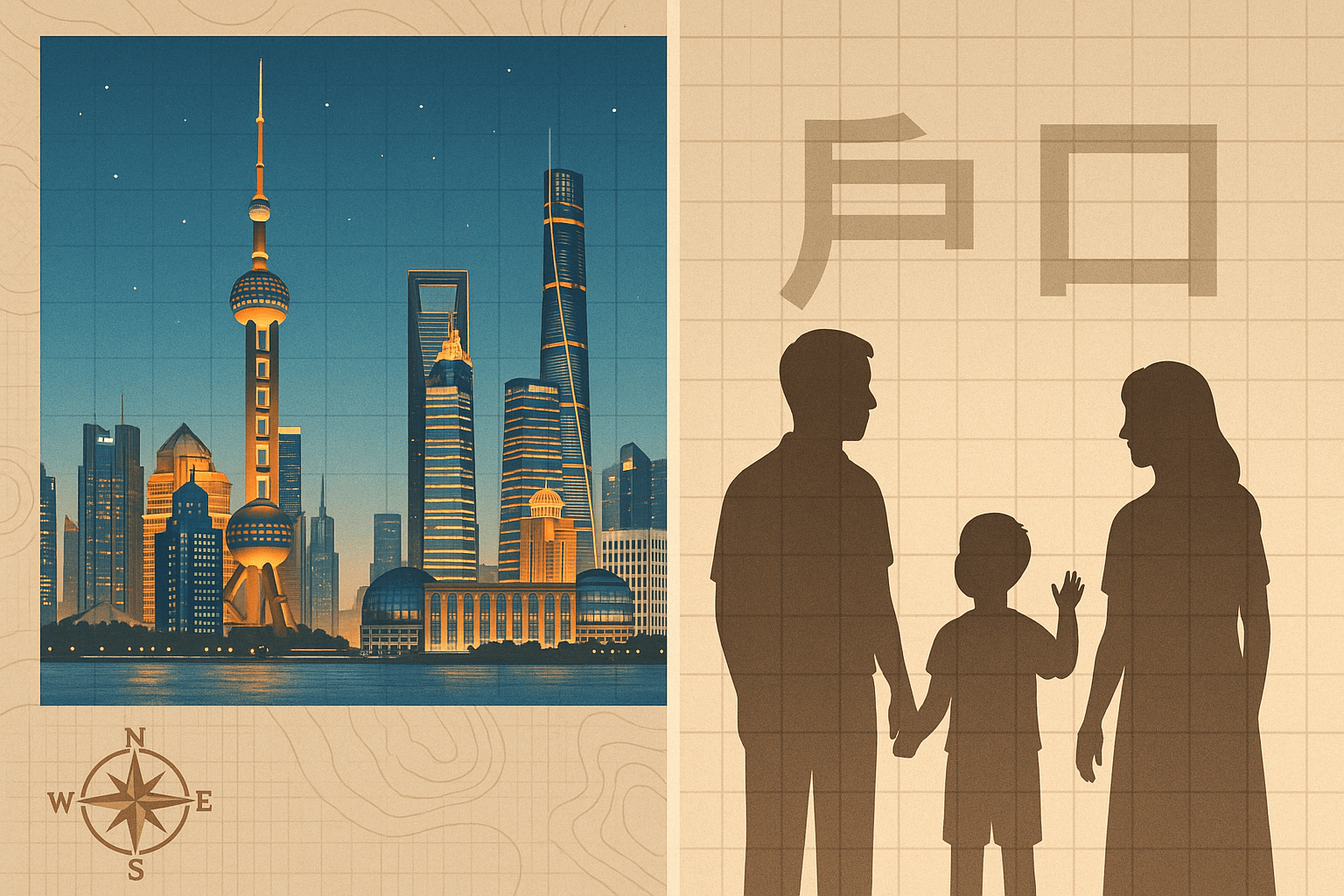

Walk through the dazzling financial district of Shanghai or the sprawling tech campuses of Shenzhen, and you are witnessing the engine of modern China. Gleaming skyscrapers pierce the clouds, and high-speed trains weave through landscapes of immense prosperity. But look closer, beyond the gleaming façade, and you’ll find a parallel reality. It’s the world of the construction workers who build those towers, the delivery drivers who fuel the e-commerce boom, and the cleaners who maintain the city’s shine. These individuals are the lifeblood of urban China, yet for many, they are outsiders in their own country, separated from the city’s full privileges by an invisible, yet formidable, barrier: the hukou system.

This system, a household registration policy, acts as a kind of internal passport, creating a “paper wall” that has profound geographical consequences, shaping the very map of inequality across the nation.

What is the Hukou? A Geographical Anchor

Established in 1958, the hukou (户口) system was designed to control internal migration, manage resource distribution, and maintain social order. Every citizen is registered at birth in a specific location, typically their family’s ancestral home. Critically, this registration is not just a line in a government ledger; it geographically anchors a citizen’s access to a whole suite of social welfare rights, including:

- Public education for children

- Subsidized healthcare and health insurance

- Pensions and unemployment benefits

- The right to buy property in certain cities

Historically, the most significant division was between an agricultural (rural) hukou and a non-agricultural (urban) hukou. An urban hukou was the golden ticket, granting access to the state-cradled “iron rice bowl” of guaranteed employment, housing, and social services. A rural hukou, by contrast, tied individuals to farming collectives with far fewer benefits. While reforms have blurred these lines, the fundamental principle remains: your rights are tied to your place of registration, not your place of residence.

The Great Migration and the “Floating Population”

China’s economic miracle, which kicked off in the late 1970s, created an insatiable demand for labor in newly established Special Economic Zones and coastal manufacturing hubs. This sparked one of the largest migrations in human history. Tens, and then hundreds, of millions of people left their rural villages in provinces like Sichuan, Henan, and Anhui, flocking to the booming megacities of the Pearl River Delta (like Guangzhou and Shenzhen) and the Yangtze River Delta (like Shanghai).

However, they couldn’t simply move and become a citizen of their new city. Their hukou remained in their home village. This created a massive demographic phenomenon known as the “floating population” (流动人口, liúdòng rénkǒu). Today, this group numbers over 370 million people—a population larger than that of the United States—living and working outside their official registered home. They are urban residents in practice, but rural citizens on paper.

The Urban Geography of Segregation

The hukou system carves invisible, yet deeply felt, borders within China’s cities, creating a unique geography of internal segregation.

Education: A Tale of Two Childhoods

Perhaps the most punishing aspect of the hukou system is its impact on children. A child’s access to the local public school system is tied to their parent’s hukou. For migrant workers, this means their children are often barred from the well-funded public schools that the children of registered urbanites attend. Their options are grim:

- Return to the village: This has created the heart-wrenching phenomenon of “left-behind children”, an estimated 60 million children who grow up in rural villages raised by grandparents while their parents work hundreds of miles away in the cities. This bifurcates the geography of the family itself.

- Attend migrant schools: In the cities, a patchwork of private, often unaccredited, and under-resourced schools have sprung up to serve the migrant community. These schools are frequently located on the urban periphery and face the constant threat of being shut down by authorities.

Healthcare and Housing: Life on the Margins

This segregation extends to health and housing. Without a local hukou, migrant workers are often excluded from urban health insurance schemes, forcing them to pay for expensive medical care out-of-pocket or make the long journey back to their registered village for treatment. This creates a geography of healthcare access where the quality of care one receives can depend on a document, not a diagnosis.

In terms of physical space, the hukou system shapes the very layout of the city. Unable to afford or legally purchase homes in the formal market, many migrants are concentrated in specific areas. They cluster in “urban villages” (城中村, chéngzhōngcūn)—pockets of old village land that have been swallowed by urban expansion but retain a different administrative status. These are dense, low-rent enclaves with poor infrastructure, existing as islands of informality amidst the modern metropolis. Other workers live in crowded, factory-provided dormitories, their entire existence confined to a separate geographical circuit of work and rest.

The Hollowed-Out Countryside

The geographical impact isn’t limited to the cities. As waves of working-age adults leave the countryside, they leave behind what geographers call a “hollowed-out” landscape. Villages populated mainly by the elderly and children face a slow collapse of their social and economic fabric. Fields may lie fallow, local businesses close, and the community’s vitality drains away, creating vast regions of demographic and economic stagnation that stand in stark contrast to the hyper-dynamism of the coastal cities.

Are There Cracks in the Paper Wall?

The Chinese government is aware of the problems the hukou system creates. In recent years, reforms have attempted to chip away at the wall. Many small and medium-sized cities have completely dropped hukou restrictions to attract talent and labor. Even larger cities have introduced “points systems”, allowing highly educated and high-earning migrants to slowly earn eligibility for a coveted local hukou.

However, for the vast majority of low-skilled migrant workers, the wall remains firmly in place, especially in top-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai, where a local hukou is more valuable than ever. The wall has become less of a solid barrier and more of a highly selective filter, allowing the “best and brightest” to integrate while keeping the manual laborers who power the city at arm’s length.

The hukou system is far more than a bureaucratic tool. It is a fundamental force that has sculpted China’s modern geography, directing the largest migration in history while simultaneously drawing sharp lines of inequality across the urban and rural landscape. As China moves into the future, its greatest challenge may not be building more skyscrapers, but figuring out how to finally tear down this paper wall and create one, truly integrated nation.