The Dust of Ages: What is Loess?

To understand the Loess Plateau, you must first understand loess itself. It is not ordinary soil. Loess is a sediment, a vast deposit of silt blown by wind over millennia. During the last Ice Age, massive glaciers ground rocks into a fine, flour-like powder. As the ice sheets retreated, powerful winds picked up this dust from the deserts of Central Asia, particularly the Gobi, and carried it eastward. Over thousands of years, this dust settled, blanketing the north-central plains of China in layers that can be over 300 meters deep.

This wind-deposited silt has several unique properties:

- Fertility: Loess is rich in minerals like quartz, feldspar, and calcite, making it incredibly fertile and easy to till, even with simple tools.

- Porosity: The fine particles create a porous structure that can hold water, making it ideal for agriculture in a semi-arid climate.

- Vertical Cleavage: When dry, loess is surprisingly strong and has a tendency to cleave, or split, in vertical planes. This allows for the carving of stable cliffs and underground dwellings.

- Extreme Erodibility: When saturated with water, loess loses all its structural integrity. It dissolves like sugar, making it extraordinarily vulnerable to erosion by rainfall.

This last property is responsible for the region’s most famous feature: the Yellow River (黄河, Huáng Hé). The river carves its way through the plateau, picking up immense quantities of yellow silt, which gives the river its distinctive color and its name. The Yellow River is, in fact, the world’s muddiest major river, a direct consequence of the land it flows through.

Cradle of a Civilization Carved from Earth

The fertile, easily-worked soil of the Loess Plateau was the perfect catalyst for the Neolithic revolution in China. Around 7,000 years ago, early peoples began cultivating millet here, a hardy grain well-suited to the climate. This reliable food source allowed for the transition from nomadic life to settled agricultural communities, laying the groundwork for the first Chinese dynasties, including the Shang and Zhou.

The human geography of the plateau is just as unique as its physical geography. For centuries, residents have used the loess’s vertical cleavage to their advantage by carving their homes directly into the earth. These cave dwellings, known as yáodòng (窑洞), are a brilliant example of human adaptation. Dug into the sides of cliffs and hills, they are naturally insulated—cool in the blistering summer heat and warm during the freezing winters. They required few building materials and were remarkably stable. In provinces like Shaanxi and Shanxi, millions of people still live in modernized versions of these ancient homes.

A Landscape Scarred by “China’s Sorrow”

For millennia, a delicate balance existed. But as China’s population grew, the demand for food and fuel intensified. Forests that once stabilized the loess soil were cleared for farmland and firewood. Grasslands were overgrazed by livestock. Without the anchoring roots of vegetation, the fragile loess was left exposed to the elements.

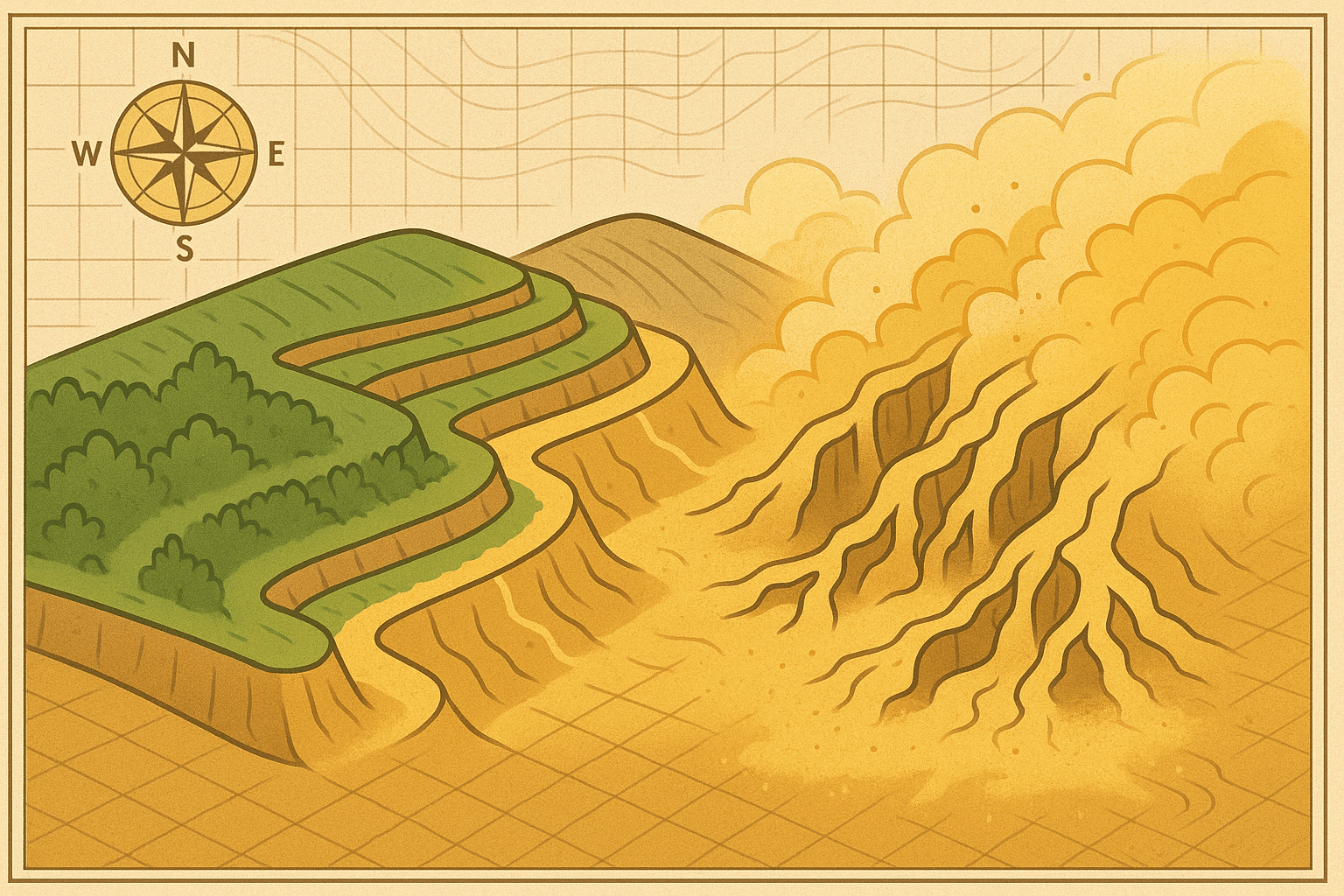

The consequences were catastrophic. The intense summer monsoon rains, instead of being absorbed by plants, tore through the bare earth, carving immense, branching gullies and ravines into the landscape. This process of water erosion, known as gullying, transformed smooth plateaus into a fractured and scarred terrain. Each year, billions of tons of topsoil were washed away—soil that had taken thousands of years to accumulate.

This sediment choked the Yellow River, causing its riverbed to rise. To contain the river, people built higher and higher levees. Eventually, the riverbed in the lower plains became elevated several meters above the surrounding countryside, creating a “suspended river.” When the levees inevitably broke, the resulting floods were devastating, drowning agricultural land and entire cities. The river earned the tragic nickname “China’s Sorrow.”

The Great Green Wall: A Modern Battle for Restoration

By the late 20th century, the Loess Plateau was an ecological disaster zone. Desertification was rampant, poverty was entrenched, and the constant threat of floods loomed downstream. In 1994, the Chinese government, in partnership with the World Bank, launched one of the most ambitious ecological restoration projects in human history: the Loess Plateau Watershed Rehabilitation Project.

The strategy was not just to plant trees, but to fundamentally rethink the relationship between people and the land. The approach was multi-faceted and targeted the root causes of the erosion:

- Terracing: Steep, erosion-prone slopes were converted into level terraces. This dramatically slows the flow of rainwater, allowing it to soak into the soil instead of running off and carrying silt away.

- Revegetation: Farmers were paid to stop cultivating on the steepest slopes. These areas were then replanted with a mix of native trees, shrubs, and grasses chosen for their ability to thrive and hold the soil.

- Grazing Bans: Free-range grazing by goats and sheep, which had stripped hillsides bare, was banned in critical areas. Farmers were encouraged to switch to pen-feeding livestock.

- Check Dams: Thousands of small dams were built in the gullies. These dams trap sediment, creating new, flat, and fertile farmland while also holding back water.

A Green Miracle and a Hopeful Future

The results have been nothing short of miraculous. In just over two decades, a vast area of the plateau has been transformed. Hills that were once barren and brown are now covered in green. The amount of sediment flowing into the Yellow River has been reduced by over one billion tons per year. Water tables have risen, and the local climate has become more humid.

For the people of the plateau, the project has been a lifeline. The new terraced fields and sediment-filled dam lands are far more productive. Incomes have more than doubled as farmers diversify their crops and benefit from the restored ecosystem. The Loess Plateau, once a symbol of environmental despair, is now hailed globally as a blueprint for how to reverse desertification and heal a broken landscape.

The journey of the Loess Plateau is a powerful testament to the profound connection between land and people. It shows how a landscape can shape a civilization, how human activity can push it to the brink of collapse, and, most importantly, how dedicated, science-based effort can bring it back to life.