Faced with a devastating combination of rapid urbanization and the escalating impacts of climate change, Chinese cities have been battling increasingly severe and frequent urban floods. The traditional approach—a “grey infrastructure” of concrete, pipes, and pumps designed to funnel water away as quickly as possible—has proven inadequate. The Sponge City plan flips this paradigm on its head. It aims to work with nature, not against it, by transforming cities into giant, porous sponges that can absorb, filter, and reuse rainwater.

The Geographical Imperative: Why China Needs Sponges

To understand the urgency behind this initiative, one must look at China’s unique geography. It’s a story written on the landscape itself, a convergence of physical and human factors that created a perfect storm for urban flooding.

Physical Geography: A Land of Extremes

Much of China’s densely populated eastern half is dominated by a powerful monsoon climate. This means a vast majority of the annual rainfall occurs during a few intense summer months. Rivers like the mighty Yangtze and Yellow River, which have nourished Chinese civilization for millennia, swell dramatically, and their vast floodplains are natural targets for inundation. As climate change intensifies weather patterns, these annual downpours are becoming more extreme and less predictable, turning what were once manageable seasonal floods into catastrophic events.

Human Geography: The Concrete Transformation

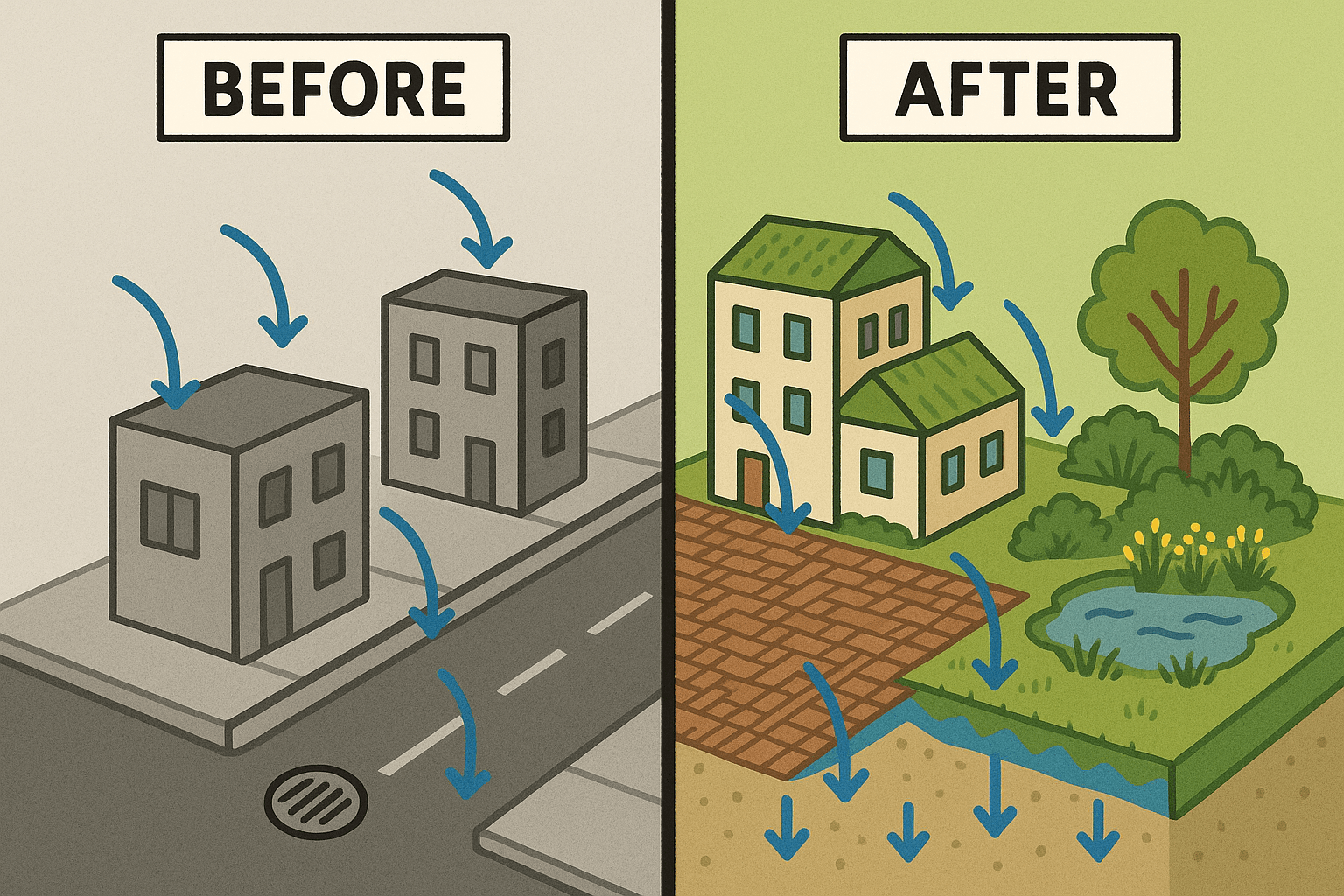

Over the past four decades, China has undergone the largest and fastest urbanization process in world history. Hundreds of millions of people have migrated from rural areas to burgeoning megacities. To accommodate this growth, vast swathes of naturally permeable landscapes—farmland, forests, and wetlands—have been paved over with impervious concrete and asphalt. These “grey” surfaces prevent rainwater from infiltrating the ground, forcing it to run off at high speeds into drainage systems that were never designed for such volumes. The result is a double-edged sword: crippling urban floods during the rainy season and severe water shortages during the dry season, as groundwater is not being replenished.

How a Sponge City Works: The Toolkit

The goal of the Sponge City initiative is ambitious: by 2030, the government wants 80% of urban areas to absorb and reuse at least 70% of their rainwater. Achieving this requires a multi-layered approach that integrates “blue” (water bodies), “green” (plants and parks), and “grey” (traditional drainage) infrastructure.

- Permeable Pavements: The foundation of the sponge. These special pavements, made from porous concrete or paving stones with gaps filled with gravel, allow rainwater to seep directly into the ground below, recharging aquifers and reducing surface runoff. They are being installed on sidewalks, in public squares, and even on low-traffic roads.

- Green Roofs and Vertical Gardens: Rooftops make up a significant portion of a city’s impervious surface area. By covering them with soil and vegetation, they are transformed into living sponges. Green roofs absorb rainwater, reduce stormwater runoff, insulate buildings (lowering energy costs), and combat the urban heat island effect.

- Bioswales and Rain Gardens: These are engineered depressions in the landscape, often found along roadways and in parking lots. Filled with native plants and specific soil layers, they are designed to slow down, collect, and filter runoff from nearby surfaces, naturally removing pollutants before the water enters the groundwater or drainage system.

- Constructed Wetlands and Retention Ponds: On a larger scale, cities are creating and restoring wetlands, lakes, and ponds. These act as the city’s kidneys and reservoirs. They can hold massive volumes of water during a storm, releasing it slowly and preventing downstream flooding. The vegetation in these wetlands also provides a powerful, natural water purification service.

From Blueprint to Reality: Sponge Cities in Action

The Sponge City concept is not just a theory. Since the initiative launched in 2015, dozens of pilot cities have been implementing these strategies with tangible results.

Wuhan: Reclaiming a Watery Heritage

Located on the flood-prone plains of the central Yangtze River, Wuhan is historically known as the “City of 100 Lakes.” Decades of development had filled in many of these natural sponges. As a pilot city, Wuhan has invested heavily in restoring lakes and creating new green spaces. The Sino-French Eco-City demonstration project in Wuhan features extensive rain gardens and a large lakeside park that doubles as a flood basin, showcasing how new developments can be built in harmony with water.

Xiamen: A Coastal Defence

This coastal city in southeast China faces the dual threats of typhoon-driven rainfall and freshwater scarcity. Xiamen’s sponge projects are designed not only to manage floods but also to capture precious rainwater to supplement its water supply and push back against saltwater intrusion into its aquifers. Its transformation of a former landfill into the beautiful Xiang’an Park, complete with a constructed wetland and permeable pathways, serves as a prime example of urban renewal through sponge principles.

Lingang, Shanghai: A City Built as a Sponge

While retrofitting old cities is a massive challenge, Lingang, a new district on the coast near Shanghai, offers a glimpse into the future. It was designed from the ground up with Sponge City principles. A massive, star-shaped lake sits at its center, connected by a web of canals and green corridors. Nearly all public spaces are designed to manage rainwater, making the entire urban fabric an integrated system for flood resilience.

Challenges and the Global Lesson

The path to a fully “spongified” China is not without obstacles. The cost of retrofitting vast, established cities is astronomical. Maintaining these green infrastructure projects requires new skills and ongoing investment. Furthermore, as the devastating floods in Zhengzhou in 2021 showed, even Sponge City infrastructure can be overwhelmed by once-in-a-thousand-year weather events. The initiative is a tool for resilience, not a magic bullet for immunity.

Despite the challenges, China’s Sponge City initiative represents a profound and necessary shift in our relationship with the urban environment. It’s a move away from the 20th-century mindset of conquering nature towards a 21st-century philosophy of co-existence. As cities across the globe—from Houston to Copenhagen to Mumbai—grapple with their own water-related crises, the lessons being learned in China’s urban laboratories offer a vital blueprint for a more sustainable, resilient, and livable future.