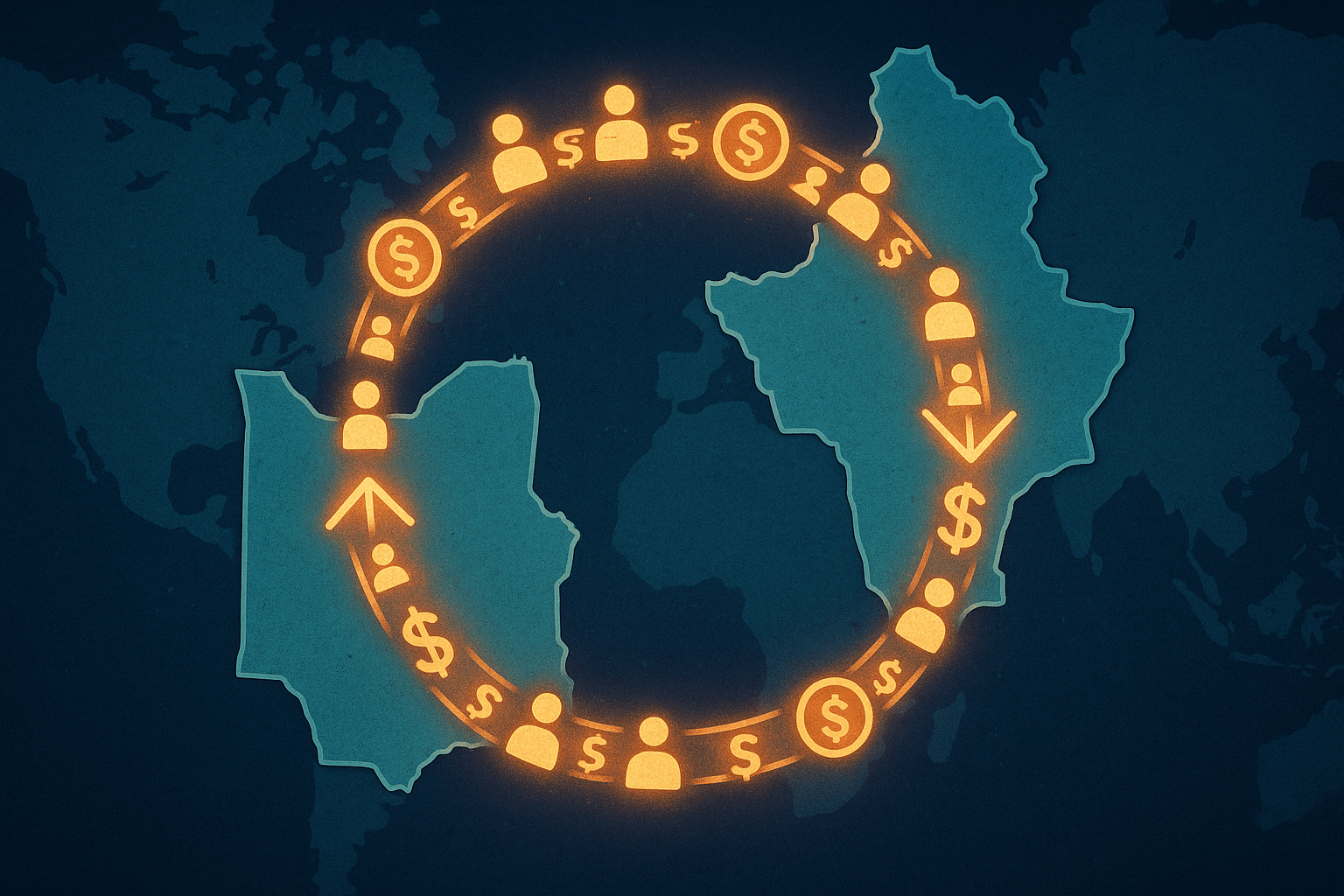

When we picture migration, we often imagine a one-way journey: a family packing their lives into suitcases, crossing a border, and starting anew in a foreign land, leaving the old one behind. While this narrative holds true for millions, it overlooks a more fluid, cyclical, and equally powerful human story. This is the world of circular migration—a repetitive, often seasonal movement of people between a home and host country, driven by the powerful forces of geography.

This isn’t tourism, nor is it permanent settlement. It’s a life lived on a rhythm, a pendulum swing between two or more places, creating unique transnational communities and economies that reshape the map in subtle but profound ways.

The Rhythms of the Earth: Physical Geography as a Driver

At its core, much of circular migration is dictated by the planet’s own cycles. The most classic example is tied to agriculture, a dance between climate, season, and labor.

- The Harvest Corridors: Consider the vast agricultural landscapes of North America. When grapes ripen in California’s Napa Valley, or apples are ready for picking in Washington’s orchards, a surge of labor is required. Many of these temporary workers come from Mexico and Central America, following the harvest seasons north. Their movement is a direct response to a geographical reality: different latitudes experience growing seasons at different times. A similar pattern unfolds across the Atlantic, where workers from Morocco and Tunisia cross the Strait of Gibraltar to harvest olives, oranges, and tomatoes in Spain and Italy. The Mediterranean Sea, a geographical barrier, becomes a conduit for seasonal labor.

- The Tourist Tides: Climate also drives tourism, another major engine of circular migration. The ski resorts of the French and Swiss Alps need instructors, hospitality staff, and maintenance workers for the winter season. Many of these positions are filled by people who, in the summer, might work in the coastal resorts of the French Riviera or Spain’s Costa del Sol. This creates a fascinating intra-European migration cycle, a human tide that ebbs and flows with the holiday seasons.

In these cases, physical geography—climate, seasons, and topography—creates temporary pockets of intense economic demand. Circular migration is the human response to that demand, a predictable flow of people moving to where the work is, fully intending to return when the season ends.

The Geography of Opportunity: Economics and Proximity

If physical geography sets the seasonal stage, human geography—specifically economics and proximity—writes the script. Circular migration thrives along gradients of economic disparity, especially where a wealthier region sits adjacent to a less affluent one.

The US-Mexico border is perhaps the world’s most prominent example. It’s not just a political line but a stark economic one. The wage differential for agricultural, construction, or service work can be immense. For a worker from a rural village in Oaxaca, a few months of work in the United States can support their family for an entire year. Proximity and established transportation networks make this repetitive journey feasible, if not always easy. Formalized systems like the H-2A (agricultural) and H-2B (non-agricultural) visa programs in the U.S. acknowledge and structure these flows.

We see similar dynamics elsewhere:

- Southeast Asia: A bustling hub of circular migration exists between Indonesia, the Philippines, and the more developed economies of Malaysia and Singapore. Laborers move for construction projects, and domestic workers take on contracts, often with the plan to return home with their savings.

- Europe: The expansion of the European Union radically redrew the map of labor mobility. Workers from Poland, Romania, and Lithuania began moving to the UK, Ireland, and Germany for higher-paying jobs in construction and services. While some stayed permanently, many adopted a circular pattern, working abroad for several months or years before returning home, often investing their earnings in a house or a small business.

Mapping Transnational Spaces: Where Two Worlds Meet

Circular migration does more than move people; it forges new kinds of places. It creates transnational communities, where a single community’s social and economic life is stretched across thousands of miles. The geography of both the home and host countries is permanently altered.

The Impact on “Home”

Walk through a village in Michoacán, Mexico, or a town in the Philippines, and you can often see the architectural signature of migration. You’ll find “remittance houses”—homes built or improved with money sent back from abroad, often larger and more modern than their neighbors. These remittances become the lifeblood of the local economy, funding small businesses, improving infrastructure, and changing the very landscape of the town. The community’s center of economic gravity is, in a sense, located hundreds or thousands of miles away.

The Footprint in the “Host”

In the host country, these flows leave their own mark. While temporary, migrant communities create demand for specific cultural goods. In cities like Los Angeles or Chicago, neighborhoods pulse with the life of these transnational ties. You’ll find shops selling phone cards for calling home, cargo companies specializing in sending boxes of goods back to Mexico or the Philippines, and restaurants that serve as social hubs for diasporic communities. These spaces are hybrid, a slice of a distant home embedded within a new urban fabric.

A Constantly Shifting Map

Circular migration is not a static phenomenon. Its pathways are constantly being rerouted by political, economic, and even environmental shifts. A change in visa policy can shut down a corridor that has existed for generations. An economic recession can reduce labor demand, causing the pendulum to stop swinging. Conversely, new free-trade agreements or transportation links can open up entirely new routes.

Looking forward, climate change is poised to become a major disruptor and driver. As traditional agricultural areas face drought or extreme weather, the seasonal labor patterns they support may falter. At the same time, new demands, such as for “green” construction or disaster recovery, could create entirely new reasons for people to move in cyclical patterns.

Understanding circular migration forces us to see the world map not as a fixed puzzle of nation-states, but as a dynamic web of human connection. It’s a geography defined by flows, rhythms, and the enduring human quest for a better livelihood—even if it means living a life perpetually between two worlds.