Look at a map. Any map. A world atlas, a city street guide, or the GPS on your phone. What do you see? You probably see a neutral, scientific representation of the world—a tool for getting from Point A to Point B. But what if a map is more than that? What if it’s a story, a declaration, or even an act of rebellion?

For centuries, the power to draw the map has been the power to define reality. Colonial powers drew lines across continents, creating countries while erasing entire cultures. Corporations map out resources for extraction, ignoring the sacred groves and ancestral hunting grounds that lie in their path. The official map, the one printed in textbooks and hung in government offices, often tells a story of power, ownership, and control—a story that renders many people invisible. But a powerful movement is redrawing the lines. This is counter-mapping, and it’s one of the most vital frontiers in the fight for spatial justice.

The Map as a Weapon

Before we can understand counter-mapping, we must first deconstruct the traditional map. Far from being objective, maps are inherently political. The choices a cartographer makes—what to include, what to exclude, what to name, and what to leave nameless—are acts of power. For example, the common Mercator projection, while useful for navigation, famously distorts the planet, enlarging Europe and North America while shrinking Africa and South America. This visual distortion has subtly reinforced colonial-era hierarchies for centuries.

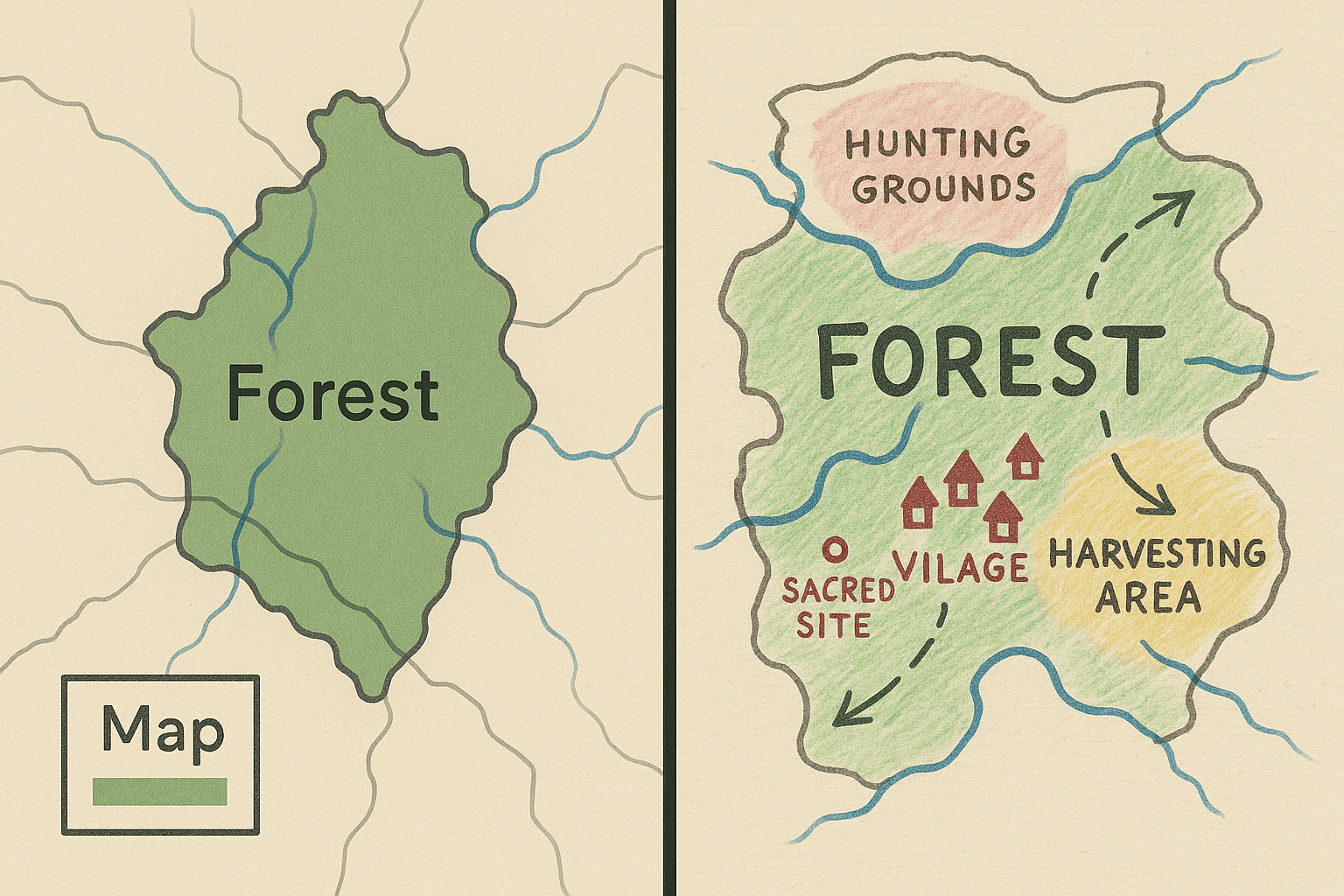

For indigenous communities and marginalized groups, this isn’t just an academic problem. Official maps often represent their ancestral lands as empty, a terra nullius (“nobody’s land”) ripe for development. They might show a forest, but not the complex web of human activity within it:

- Sacred burial grounds and ceremonial sites.

- Paths for hunting and migration passed down through generations.

- Areas rich with medicinal plants known only to local healers.

- Local place names that hold deep historical and cultural meaning.

When this knowledge is omitted, it’s a form of erasure. It makes it easier for governments and corporations to claim that “nothing is there”, justifying the construction of a dam, the clear-cutting of a forest, or the drilling of an oil well. The map becomes a weapon used to dispossess and displace.

Counter-Mapping: Taking Back the Narrative

Counter-mapping, also known as participatory mapping or ethnocartography, flips the script. It’s a process where communities reclaim the technology of cartography to tell their own story of place. Instead of a top-down map created by distant experts, it’s a bottom-up process rooted in local knowledge and lived experience.

“Counter-mapping is about communities taking the tools of the colonizer, the tools of the state, and using them to assert their own reality, their own rights, and their own vision for the future.”

The goal isn’t just to make a different-looking map. It’s to produce a tool for resistance, advocacy, and cultural survival. These maps serve as powerful evidence in courtrooms, as rallying points for political movements, and as invaluable archives for future generations.

Dispatches from the Front Lines of Cartography

The practice of counter-mapping is happening all over the globe, from the dense rainforests of the Amazon to the icy expanses of the Arctic and the concrete canyons of our biggest cities.

The Kayapó People of the Amazon

In the Brazilian Amazon, the Kayapó people have faced decades of pressure from illegal logging, gold mining, and agricultural encroachment. To protect their vast, forested territory, they embarked on a groundbreaking counter-mapping project. Combining the intricate knowledge of their elders with modern GPS technology, they meticulously mapped their 11 million-hectare territory. Their maps didn’t just show a border; they depicted a living landscape, detailing trails, fishing spots, ancient village sites, and areas rich in biodiversity. Armed with these maps, they successfully lobbied the Brazilian government for legal recognition of their land, creating one of the largest protected blocks of tropical rainforest in the world. Their map was not just a picture of the land; it was an irrefutable argument for its preservation.

The Inuit of Clyde River vs. Big Oil

In the Canadian Arctic, the Hamlet of Clyde River faced a threat from a consortium of energy companies planning to conduct seismic testing for oil and gas in Baffin Bay. This process involves firing powerful underwater airguns, which could devastate the marine mammals—narwhals, seals, and bowhead whales—that are central to Inuit subsistence and culture. The community fought back, and a key part of their strategy was mapping. They created detailed maps of the sea ice, showing traditional travel routes, hunting areas, and the precise locations where key species congregated. These maps made the invisible visible, translating their deep, intergenerational knowledge of the marine environment into a format the legal system could understand. In 2017, their fight went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in their favor, affirming that the community had not been properly consulted.

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP)

Counter-mapping is not confined to remote regions. In cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York, the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project uses data visualization and digital storytelling to fight displacement. They create interactive online maps that show where evictions are happening, who is being displaced, and which corporate landlords are responsible. But they go further, layering this data with oral histories, video interviews, and tenant testimonials. Their maps, like “(Dis)location”, don’t just show data points; they reveal the human stories of gentrification and the fabric of communities being torn apart. It is a powerful form of urban resistance, using cartography to expose the forces of spatial injustice in the modern city.

From Pen and Paper to Participatory GIS

The tools of counter-mapping are as diverse as the communities that use them. Some of the most powerful maps begin with simple conversations, sketched out on large sheets of paper on a community hall floor. But increasingly, activists are leveraging technology.

Participatory GIS (Geographic Information Systems) allows communities to layer different types of information onto a digital map. A base layer from a satellite image can be overlaid with GPS tracks of hunting trails, hand-drawn locations of sacred sites, and notes from community elders. This fusion of scientific data and traditional knowledge is what makes these maps so compelling and legally robust.

Redrawing a More Just World

Counter-mapping teaches us a profound lesson: a map is never just a map. It is an argument. It is a story. It is a claim to existence. By putting themselves back on the map, indigenous communities and activists are not just drawing lines on a page; they are charting a course toward a more equitable future. They are demonstrating that the world is far richer, more complex, and more human than any official map has ever dared to show.