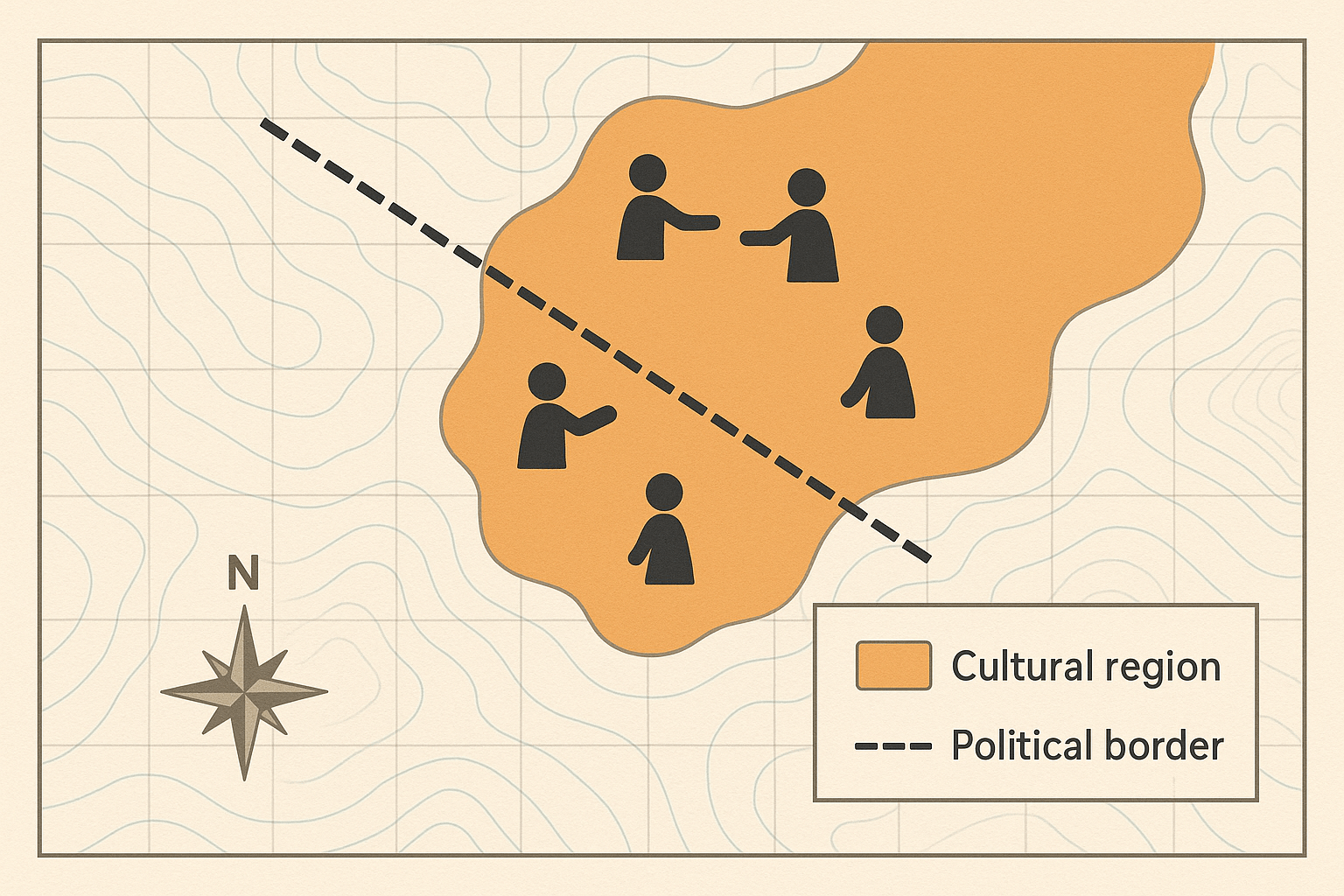

Look at a political map of the world. It’s a mosaic of neatly defined countries, their borders drawn with crisp, confident lines. But these lines, often forged in distant colonial offices or at the stroke of a post-war pen, tell a deceptively simple story. On the ground, they frequently slice through ancient homelands, bisecting communities that share a common language, culture, and history. This is the geography of divided nations—a world where the political map clashes with the human map, creating zones of persistent tension, identity crisis, and conflict.

The Durand Line: A Scar Across the Hindu Kush

Perhaps no border better illustrates this phenomenon than the Durand Line. Established in 1893 between British India and Afghanistan, this 2,670-kilometer (1,660-mile) boundary was intended to create a buffer zone against Russian expansion. The problem? It was drawn directly through the heart of Pashtunistan, the traditional homeland of the Pashtun people.

The physical geography of this border is formidable. It snakes through the towering, inhospitable peaks of the Hindu Kush and the Sulaiman Mountains. This rugged terrain has always fostered a fierce independence among the Pashtun tribes, making the border nearly impossible to police. Today, it divides the Pashtun population between Afghanistan, where they are the largest ethnic group, and Pakistan, where they are a significant minority concentrated in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Cities like Peshawar in Pakistan and Kandahar and Jalalabad in Afghanistan remain vibrant centers of Pashtun culture, yet they lie on opposite sides of an international border.

The political consequences are profound. Afghanistan has never formally recognized the Durand Line as a legitimate border, viewing it as a colonial imposition. This has fueled Pashtun nationalism and created a deeply porous frontier, a geographical reality that has enabled the cross-border movement of refugees, smugglers, and militant groups for decades, profoundly shaping the geopolitics of the entire region.

The Kurds: A Nation Without a State in a Mountainous Citadel

While the Pashtuns are divided between two countries, the Kurds represent a nation scattered across four. “Kurdistan”, a term referring to their geo-cultural homeland, is not a sovereign state but a vast region sprawling across the mountainous interiors of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria.

The geography of Kurdistan is central to their identity. It is a land dominated by imposing mountain ranges like the Zagros and Taurus Mountains. This terrain has served as both a sanctuary and a fortress, allowing the Kurds to maintain their distinct culture and language against centuries of pressure from larger, surrounding empires. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire following World War I, the victorious Allied powers initially promised the Kurds a state in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres. This promise was broken just three years later with the Treaty of Lausanne, which solidified the modern borders of Turkey and left the estimated 35-40 million Kurds as minority populations in newly formed states.

The result is a map of persistent struggle:

- In Turkey, the largest Kurdish population faces assimilation policies, with major cultural centers in cities like Diyarbakır.

- In Iraq, the Kurds have achieved a significant degree of autonomy in the Kurdistan Region, with its capital at Erbil, a testament to their political resilience.

- In Syria, the chaos of the civil war allowed Syrian Kurds to carve out a self-governing region known as Rojava.

- In Iran, the Kurdish population in the country’s west, around cities like Mahabad, continues to face repression.

The division of Kurdistan is a textbook example of how border-drawing without regard for ethnic geography creates a permanent state of political instability and a heart-wrenching quest for self-determination.

Africa’s Colonial Borders: A Legacy of Division

The “Scramble for Africa” in the late 19th century saw European powers carve up the continent with rulers on maps, paying little heed to the thousands of distinct ethnic and linguistic groups on the ground. The legacy of these arbitrary lines is felt across Africa today.

Consider the Maasai, a semi-nomadic pastoralist people whose traditional lands straddle the border between Kenya and Tanzania. Their entire way of life is based on seasonal migration with their cattle, following the rains and fresh grass across the vast plains of the Serengeti and Maasai Mara. The international border, an invisible line across the savanna, disrupts these ancient migratory routes, restricts access to water and grazing resources, and complicates issues of citizenship and belonging for a people who have always been connected to the land, not the state.

Similarly, the Ewe people of West Africa find themselves split among Ghana, Togo, and Benin, while the Tohono O’odham Nation’s sovereign lands in the Sonoran Desert are bisected by the US-Mexico border, with a border wall now physically severing communities and sacred sites.

Lines on a Map, Realities on the Ground

From the rugged mountains of Kurdistan to the vast savannas of East Africa, the story is the same: political borders are often a poor reflection of human geography. They can create minority populations where none existed, sever economic and social ties, and sow the seeds of conflict that can last for generations.

Understanding the geography of these divided populations is essential to understanding modern geopolitics. It reminds us that maps are not just neutral representations of the world; they are documents of power. The lines they contain may define states, but they do not erase the deeper, more enduring connections of people to their culture, their kin, and their land.