Mapping an Empire: The Colonial Imprint

To understand the significance of the changes, we must first look at the map the new government inherited. The colonial map of Rhodesia was an atlas of conquest. Places were not named; they were claimed. The names imposed by British settlers served two purposes: to honor the architects of empire and to erase the indigenous presence from the landscape.

The capital, Salisbury, was named for the British Prime Minister at the time of the colony’s founding, Lord Salisbury. Other towns like Fort Victoria and Fort Charter bore names that evoked military conquest and control. Even the country’s most spectacular natural wonder, known for centuries to the local Lozi and Tonga people as Mosi-oa-Tunya (“The Smoke That Thunders”), was unilaterally renamed Victoria Falls by David Livingstone in honor of the British queen. The geography of Rhodesia was a ledger of British heroes, administrators, and royalty, effectively overwriting thousands of years of local history and connection to the land.

This cartographic dominance was a key tool of colonialism. By controlling the names on the map, the settler regime controlled the narrative, rendering the African population invisible in the official geography of their own ancestral home.

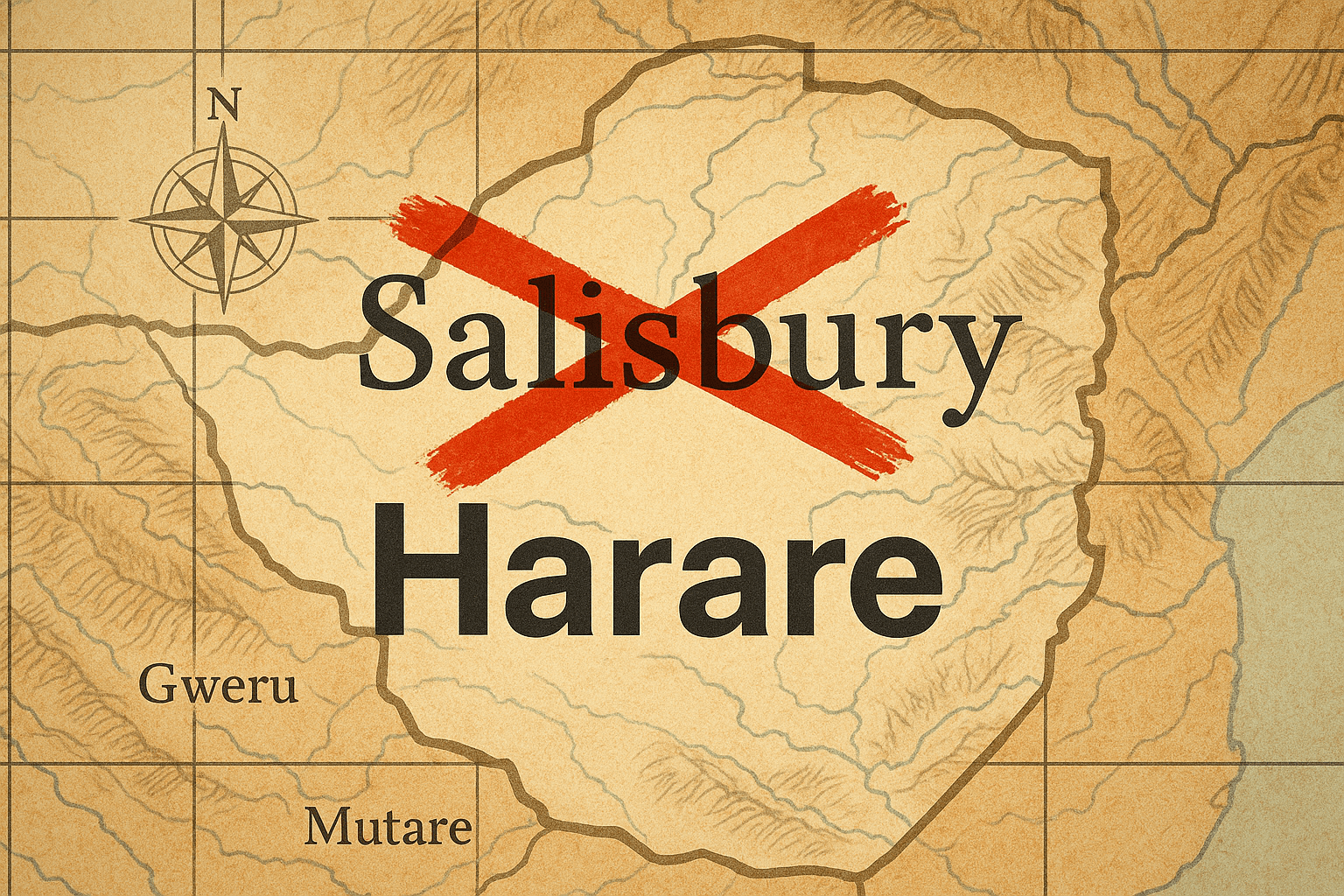

Rewriting the Atlas: From Salisbury to Harare

The new government of Zimbabwe, led by Robert Mugabe, immediately recognized the power held in place names. In 1982, two years after independence, it initiated a sweeping program of name changes for cities, towns, and streets. This wasn’t merely cosmetic; it was a deliberate act of nation-building and psychological liberation.

The changes followed a clear and symbolic logic, aiming to restore African heritage to the landscape. The capital, Salisbury, became Harare, named after the Shona chief Neharawa, who had ruled the area before the settlers arrived. The project was comprehensive, with major towns across the country reverting to indigenous names, many of which were simply corrected spellings of the original names that had been anglicized or mispronounced by colonists.

A Journey Across the New Map

The list of primary changes illustrates the scale of this geographical reclamation:

- Country: Rhodesia → Zimbabwe

- Capital: Salisbury → Harare

- Fort Victoria: → Masvingo (A Shona word for “fort” or “walled city”, linking it directly to nearby Great Zimbabwe)

- Umtali: → Mutare

- Gwelo: → Gweru

- Wankie: → Hwange

- Marandellas: → Marondera

- Sinoia: → Chinhoyi

- Gatooma: → Kadoma

Each change re-anchored a place in its local context. Masvingo, for example, not only shed its colonial military name (“Fort Victoria”) but adopted one that celebrated the very pre-colonial ingenuity the settlers had often tried to deny.

Beyond the Cities: A Deeper Reclamation

The decolonization of the map extended beyond major urban centers, seeping into the physical and human geography of the nation in more subtle ways.

Street names, the everyday geography of a city’s residents, were a primary target. In Harare, roads named for colonial figures like Cecil Rhodes, Starr Jameson, and Alfred Beit were renamed to honor heroes of the Chimurenga (the liberation struggle). Streets now bear the names of figures like Josiah Tongogara, Herbert Chitepo, and Jason Moyo. This renaming also embraced a wider Pan-African identity, with major avenues dedicated to leaders like Samora Machel of Mozambique and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, geographically cementing Zimbabwe’s place within the story of a liberated continent.

In the realm of physical geography, the changes were sometimes more nuanced. While the global name Victoria Falls has persisted due to its international tourism recognition, the Zimbabwean government and its people actively promote and use its indigenous name, Mosi-oa-Tunya. Similarly, rivers like the Lundi and Nuanetsi were officially restored to their original Shona names, Runde and Mwenezi.

An Unfinished Map: Politics, Memory, and Place

This process of toponymic reform, however, is rarely simple or complete. The act of renaming is inherently political, and it involves choosing which history to commemorate. In Zimbabwe, the names chosen overwhelmingly celebrated heroes from the ZANU party’s military wing, ZANLA, sometimes at the expense of figures from the rival ZAPU/ZIPRA liberation movement. The new map, therefore, reflected not only a break from a colonial past but also the power dynamics of the new political era.

Furthermore, the process is unfinished. Many smaller towns, commercial farms, and suburbs retain their colonial-era names, either due to the sheer logistical cost of changing them or a lingering sense of local identity. The map of Zimbabwe is thus a palimpsest, a document on which new text has been written, but where traces of the old are still visible.

More controversially, later name changes under Mugabe’s rule, such as the renaming of Harare International Airport to Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport, shifted the focus from collective liberation heritage to the legacy of a single leader, illustrating how the political power of naming can be used for different ends.

The Power of a Name

The transformation of Rhodesia’s map into Zimbabwe’s is a powerful lesson in human geography. It demonstrates that maps are not static, objective representations of the world. They are social constructions—documents of power, identity, and memory.

For Zimbabwe, rewriting the map was a necessary act of defiant self-definition. It was a way to speak back to the empire and declare that the land, its history, and its future belonged to its people. While the names on the signs changed overnight, the deeper change was in the “mental map” of the nation, providing a new geographical vocabulary for a new Zimbabwe. The country’s atlas today tells a richer, more complex story—one of ancient kingdoms, colonial conquest, liberation, and the ongoing struggle to define a nation’s soul, one place name at a time.