The First Line of Defense: The Power of Place

Long before the first stone was ever laid for a wall, the most crucial defensive decision was made: where to build. The founders of ancient cities were master geographers, understanding that the landscape itself could be their greatest ally. The best defense was one nature had already provided.

- The Hilltop Stronghold: The most obvious strategic advantage is height. Building on a hill, a mesa, or an acropolis offered unparalleled command and control. Lookouts could spot an approaching enemy from miles away, and any attacking force would be exhausted and exposed as they struggled uphill. Athens’ Acropolis and Edinburgh’s Castle Rock are classic examples, founding settlements built upon dramatic, defensible rock formations that dominated the surrounding plains.

- The Water-Bound Fortress: Water is a formidable barrier. A city built on an island, like Paris’s original settlement on the Île de la Cité in the Seine, or nestled in the sharp bend of a river, like Bern, Switzerland, in its Aare River U-bend, had a natural moat. This geography drastically limited the number of attack vectors, forcing any aggressor to cross at heavily fortified bridges.

- The Coastal Citadel: For maritime powers, the coast was both a lifeline and a vulnerability. A perfect defensive site was a rocky promontory or a sheltered bay with a narrow entrance. The walled city of Dubrovnik, Croatia, clings to a coastal cliff, presenting a formidable stone face to the Adriatic Sea. Similarly, Saint-Malo in France rises from a granite island, a fortress against both invaders and the fierce tides of the English Channel.

This initial choice of site—the physical characteristics of the land—was paramount. It was a city’s first and most enduring defensive feature, a geographical foundation upon which all other protections were built.

Engineering Invincibility: Walls, Moats, and Star Forts

Where nature’s defenses left off, human ingenuity took over. The city wall is the most iconic element of defensive urbanism, but it was a technology that evolved dramatically in response to new military threats.

Early curtain walls, like those of ancient Jericho, were simple barriers. Medieval engineers improved upon them with tall stone ramparts, projecting towers for archers to fire down (flanking fire), and battlements for soldiers to shelter behind. The magnificent, double-walled city of Carcassonne in France is a textbook example of this medieval ideal.

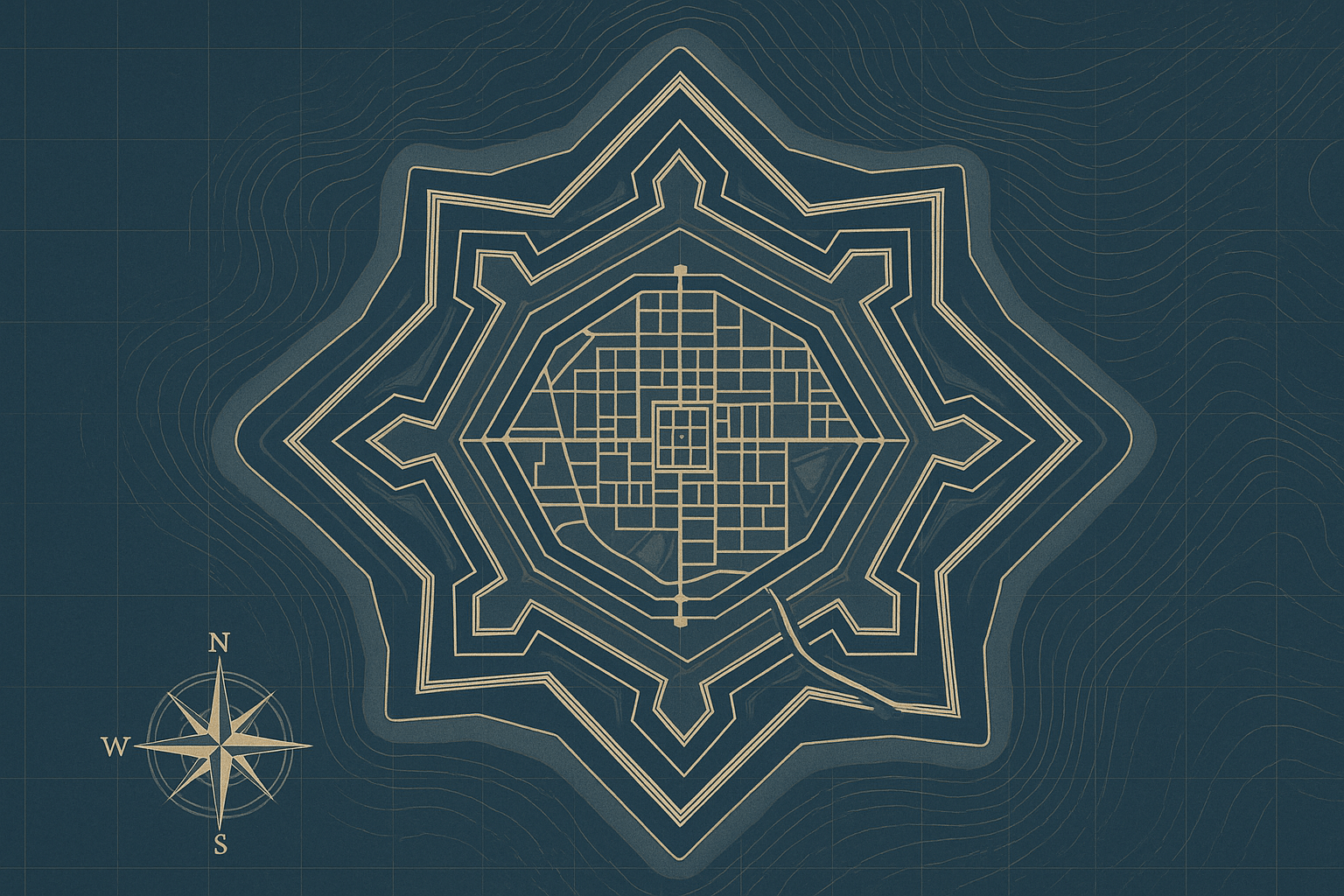

Then came the cannon. Gunpowder rendered tall, thin medieval walls tragically obsolete, as cannonballs could shatter them with ease. This existential threat sparked a revolution in military architecture, leading to the birth of the trace italienne, or the star fort.

These were marvels of geometric engineering:

- Low and Thick: Instead of rising high, star fort walls were low, squat, and incredibly thick, often reinforced with earth to absorb the impact of cannonballs.

- Angled Bastions: The distinctive star shape came from triangular bastions that projected from the corners. This ingenious design eliminated “dead zones”—blind spots where attackers could hide from defenders’ fire. Every inch of the wall’s base was covered by overlapping fields of fire from an adjacent bastion.

- Moats and Glacis: These fortifications were almost always fronted by a wide ditch or moat (wet or dry) and a gently sloping open field called a glacis. This forced attackers into a clear, open killing ground, completely exposed to cannon and musket fire from the bastions.

The Italian city of Palmanova, founded in 1593, is the perfect specimen: a flawlessly symmetrical nine-pointed star, designed from scratch to be the ultimate Renaissance fortress. Other stunning examples include Naarden in the Netherlands and the Fortress of Bourtange, which look like intricate, green snowflakes from above.

The City as a Weapon: Streets as Chokepoints

Defense didn’t stop at the outer walls. If the enemy did manage to breach the gates, the city’s internal layout became the final, desperate line of defense. The chaotic, maze-like street plan of many old city cores was, in fact, a deliberate defensive strategy.

Unlike the open, efficient grid systems of Roman or modern cities, the medieval street was a weapon. Narrow, winding alleys were designed to:

- Break Formations: A charging cavalry unit or a disciplined phalanx of infantry would be instantly broken up and thrown into confusion.

- Create Chokepoints: The streets channeled invaders into tight spaces, perfect for ambushes from defenders firing from windows and rooftops.

- Confuse and Disorient: An invading force, unfamiliar with the labyrinthine layout, could easily get lost, separated, and picked off one by one.

The medina of Fes, Morocco, is perhaps the world’s greatest surviving example of this principle. Its more than 9,000 alleys, many of them dead ends, form an almost impenetrable urban maze. Similarly, the old Jewish Quarter of Toledo, Spain, is a web of tight, twisting lanes where it would be folly for an organized army to venture.

The Legacy of Defensive Urbanism

The age of the fortress city began to wane in the 19th century. Advances in artillery made even the most sophisticated star forts vulnerable, and the rise of powerful nation-states with large standing armies shifted the focus of warfare from sieging cities to battles between armies in the open field.

As cities modernized, many tore down their now-obsolete walls to create space for growth. Yet, the ghost of the fortress city remains etched into the modern urban landscape. In Vienna, the grand Ringstrasse boulevard follows the exact path of the old city walls. In countless European cities, roads still bear names like “Porte de Clignancourt” in Paris or streets ending in “-gate” in York, marking where fortified entrances once stood.

Today, the winding streets and imposing walls that were once instruments of war are now prized for their historic charm and beauty. They are a powerful reminder that for centuries, the geography of our cities was shaped not by dreams of utopia, but by the grim, practical necessity of creating a fortress against a hostile world.