A Land Drowned by Time: The Physical Geography of Doggerland

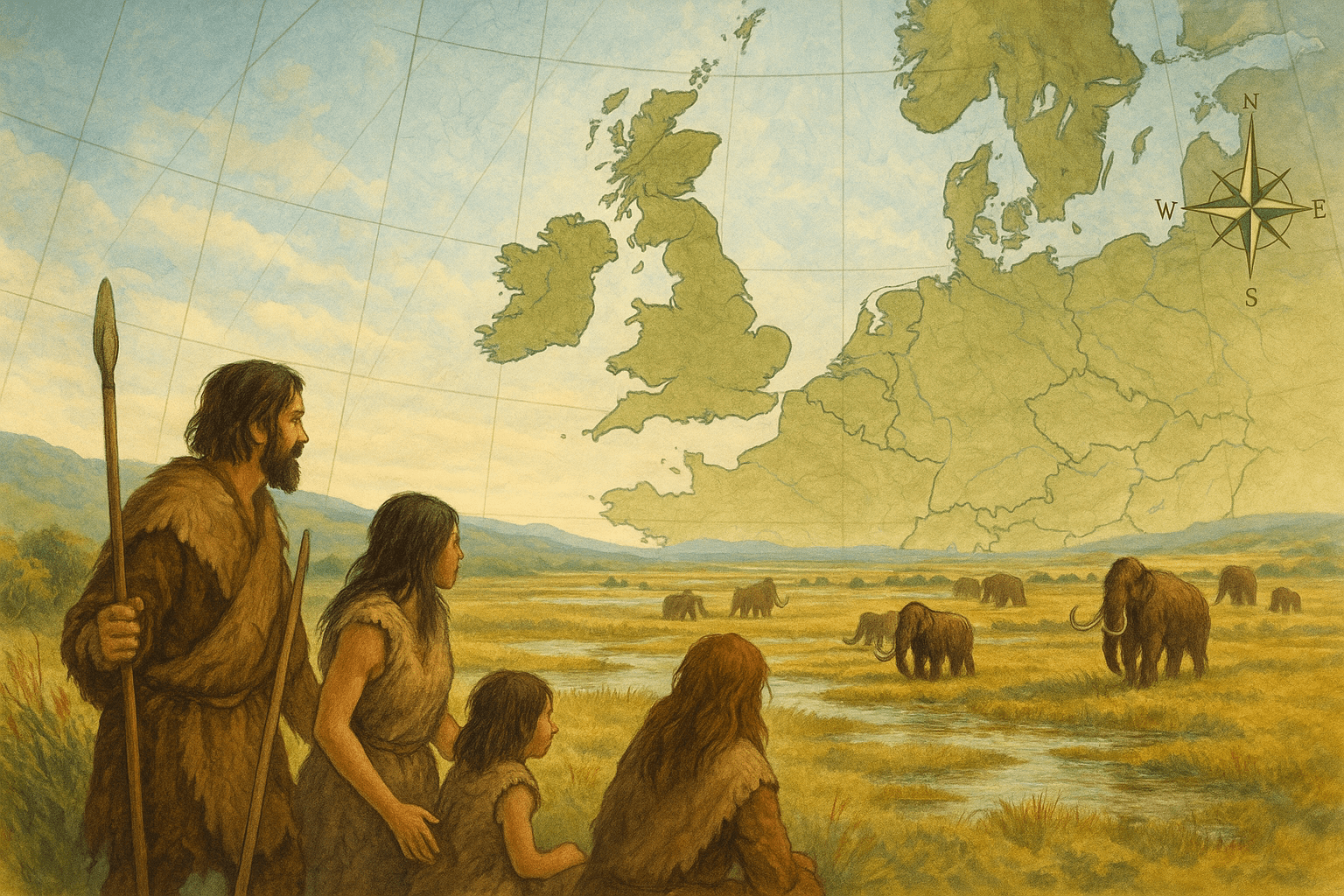

At the height of the last Ice Age, around 20,000 years ago, so much of the world’s water was locked up in massive continental ice sheets that global sea levels were about 120 meters lower than they are today. The area we now know as the southern North Sea was dry land. This was Doggerland, a territory stretching from Britain’s east coast to the modern-day Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark.

But Doggerland wasn’t just a barren, icy plain. As the climate warmed and the ice sheets retreated north, it blossomed into a rich and diverse environment. Far from being a simple land bridge, it was a destination in its own right. Seismic survey data, originally collected for oil and gas exploration, has allowed archaeologists and geologists to map this hidden world with astonishing detail. The picture that emerges is of a European heartland, a Mesolithic Eden.

The landscape was dominated by major river systems. The ancient River Thames and River Rhine didn’t flow into the sea as they do today; instead, they meandered across the Doggerland plain, meeting to form a massive freshwater estuary before finally reaching the ocean far to the north. This created a complex geography of:

- Wooded Valleys: Sheltered areas perfect for hunting and settlement.

- Vast Marshes and Wetlands: Rich in birdlife and aquatic resources.

- Low Rolling Hills: Offering vantage points for spotting game. The largest of these uplands is still detectable today as Dogger Bank, a shallow sandbank in the North Sea famous for its fishing.

This was a dynamic landscape, constantly changing as the sea levels slowly began their inexorable rise. What was once a vast, continuous plain gradually became a marshy coastline, then an archipelago of islands, before disappearing completely.

The People of the Plain: Human Geography and Mesolithic Life

This fertile landscape was not empty. It was home to Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) hunter-gatherers, people who lived in a world without farming or permanent cities. For them, Doggerland was a paradise. The rivers and coasts provided abundant fish, seals, and seabirds, while the wooded interiors were home to herds of red deer, aurochs (a type of large wild cattle), and wild boar.

How do we know they were there? For centuries, fishermen trawling the North Sea have dredged up tantalizing clues in their nets. These finds, once dismissed as curiosities, are now recognized as vital archaeological evidence. They include:

- Flint Tools: Expertly crafted scrapers, blades, and arrowheads.

- Barbed Harpoons: Carved from bone and antler, used for hunting marine mammals and large fish.

- Animal and Human Bones: Fossilized remains that sometimes show signs of butchery. In 2015, a fragment of a human skull yielded DNA, providing a direct genetic link to the people of this lost world.

These artifacts paint a picture of a sophisticated and well-adapted population. Doggerland was likely a central hub for human activity, a place where different groups could meet, trade, and exchange ideas. Its strategic location meant it was a corridor for the recolonization of Britain as the ice retreated. The people here were not isolated; they were part of a connected human geography that spanned the European continent.

The Slow Deluge: How a World Disappeared

The end of Doggerland wasn’t a single, sudden event. It was a slow-motion catastrophe that unfolded over millennia, driven by post-Ice Age climate change. As the Fennoscandian and Laurentide ice sheets melted, they released unimaginable quantities of water back into the oceans. Between 18,000 and 6,000 BCE, the sea crept inland, relentlessly consuming the low-lying plains of Doggerland.

For the inhabitants, this would have been a profound and terrifying experience. Each generation would have seen the coastline change, the hunting grounds of their parents swallowed by the encroaching sea. They would have been forced to retreat to higher ground, their world literally shrinking around them. What was once a vast territory became a large island, and then a collection of smaller, scattered isles.

While the inundation was mostly gradual, evidence points to a final, devastating cataclysm. Around 6,200 BCE, a massive underwater landslide occurred off the coast of Norway. Known as the Storegga Slide, this event displaced a volume of sediment hundreds of times greater than the eruption of Mount St. Helens. It triggered a mega-tsunami that ripped across the North Sea. Any remaining coastal settlements on the last islands of Doggerland would have been annihilated by a wall of water, an event that would have been seared into the cultural memory of any survivors who fled to the higher grounds of Britain and mainland Europe.

Mapping a Ghostly World: Doggerland Today

Doggerland is a powerful lesson from the past. It is a prehistoric case study of a population dealing with the dramatic effects of climate change and sea-level rise. Today, a new generation of explorers—archaeologists, geologists, and computer scientists—are mapping this lost world with unprecedented technology.

Projects like “Europe’s Lost Frontiers” at the University of Bradford use seismic data and sediment coring to create detailed 3D maps of the former landscape. By analyzing core samples for ancient DNA, pollen, and microscopic fossils, they can reconstruct the specific types of plants and animals that lived there. This research is not just about finding artifacts; it’s about understanding an entire ecosystem and the human response to its collapse.

The story of Doggerland is a poignant reminder that the maps we take for granted are merely a snapshot in time. Beneath the waves lies a complete, drowned country, a testament to the dynamic and sometimes destructive power of our planet’s geography. It’s a lost world that reminds us of the fragility of our own coastlines and the deep, ancestral connection between the British Isles and the European continent.