The Cairo Conundrum: A City Bursting its Seams

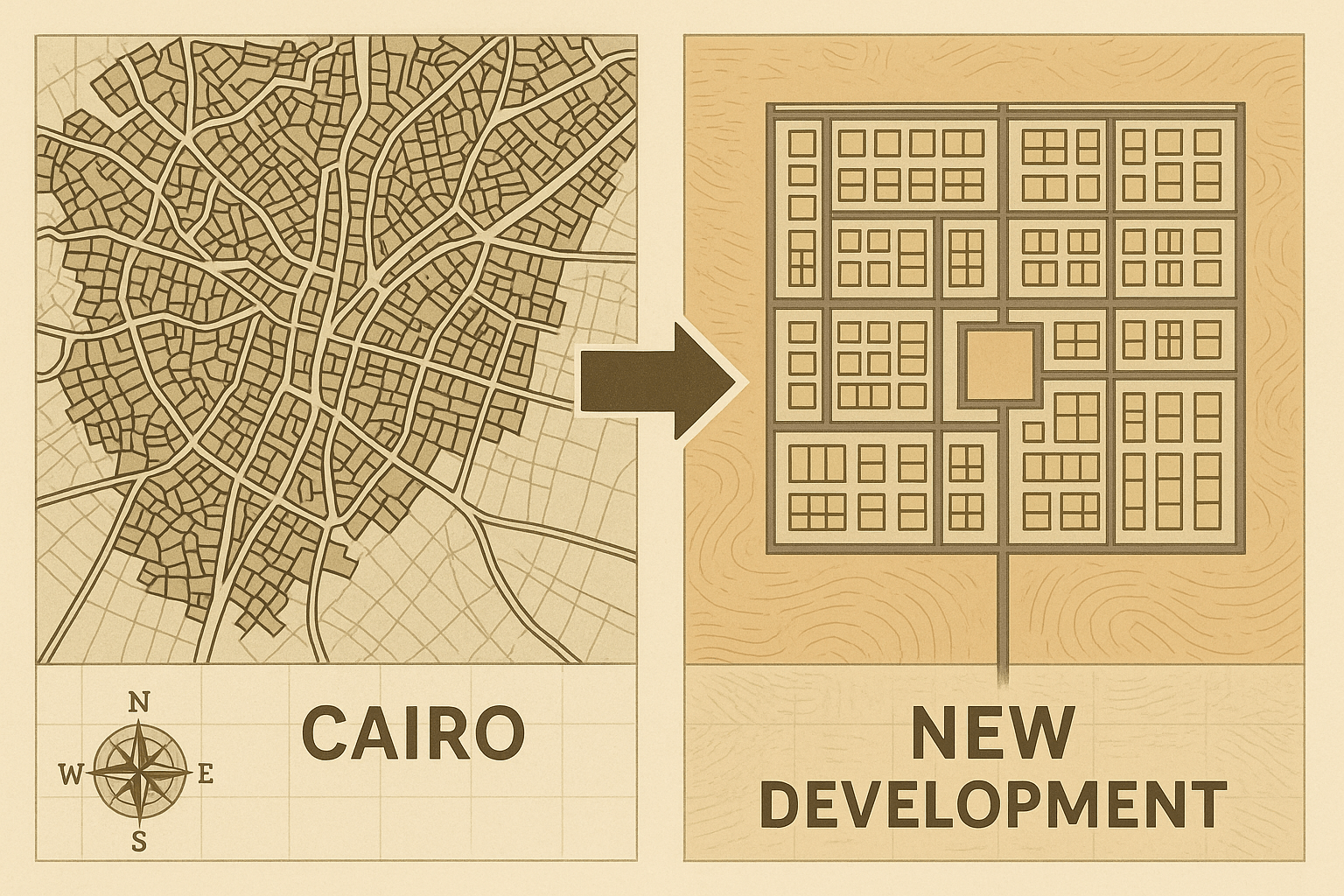

To understand the pull of the new capital, one must first grasp the push from the old one. Cairo, the current capital, is a magnificent, maddening urban behemoth. Its geography is both its blessing and its curse. Cradled by the Nile River, its growth is penned in by the fertile river valley on one side and the desert on the other. For centuries, this geography anchored Egyptian civilization, but today, it has become a straitjacket.

Greater Cairo is home to over 22 million people, and its population is projected to swell to 40 million by 2050. This hyper-concentration has led to a state of near-permanent “urban sclerosis.” The city’s infrastructure, much of it aging, is buckling under the pressure. Traffic is legendary, with commutes that can last hours, choking the air with pollution and the economy with lost productivity. Retrofitting a city with a history as deep and a fabric as dense as Cairo’s with 21st-century infrastructure is a near-impossible task. The decision to build anew is, in many ways, an admission that Cairo, in its current form, is geographically and logistically maxed out.

A New Center of Gravity: The Spatial Logic of the NAC

The NAC represents a radical break from Egypt’s historical geography. Located 45 kilometers east of Cairo, its position is no accident. It sits on a strategic corridor connecting the political and demographic heart of Cairo with the economic artery of the Suez Canal and its associated development zone. This is a deliberate eastward shift, an attempt to create a new axis of power and commerce.

Building on a tabula rasa—a blank slate of desert—offers planners an almost utopian freedom. Unlike the organic, often chaotic growth of Cairo, the NAC is a master-planned metropolis. Its design incorporates:

- Dedicated Districts: A sprawling government district to house all ministries and parliament, a central business district featuring Africa’s tallest tower (the “Iconic Tower”), and vast residential neighborhoods.

- Modern Infrastructure: The city is built around smart technology, with fiber optic networks, cashless payment systems, and sophisticated surveillance. Wide, multi-lane roads are designed to prevent the traffic jams that paralyze Cairo.

- Green Space: A central feature is the “Green River”, a massive urban park twice the size of New York’s Central Park, designed to snake through the city, providing a lung for the new urban landscape.

This spatial logic is one of control and efficiency, a stark contrast to the beautiful but often unmanageable chaos of the old capital.

Geopolitical Lines in the Sand

The NAC is more than just a solution to overcrowding; it is a powerful geopolitical statement. For the Egyptian state, the project is a symbol of a “New Republic”—modern, efficient, strong, and forward-looking. It’s a tool of national branding designed to attract foreign investment and project an image of stability and ambition to the world.

Furthermore, the physical geography of the new capital enhances state security. The government district is a self-contained, high-security zone, separated from the rest of the city. This design is widely seen as a response to the 2011 revolution, when protestors famously occupied Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo, at the doorstep of key government buildings. By moving the seat of government to a controlled, isolated environment, the state physically distances itself from the potential for mass public unrest.

This fortress-like characteristic underscores a key geographical principle: the arrangement of space is an exercise in power. The NAC is designed not just to be governed from, but to be easily governable.

Demographics in the Desert: A Tale of Two Cities?

While the logic of the move is clear from a planning and political perspective, its human geography raises profound questions. The most pressing is: who will actually live in this high-tech desert city?

The cost of housing in the NAC is far beyond the reach of the average Cairene. The target demographic appears to be government employees (who will be compelled to move), the upper-middle class, and the wealthy elite. This has sparked fears that the NAC will become a sanitized, exclusive enclave, physically and socially detached from the majority of the population it is supposed to serve.

This risks creating a stark demographic divide—a tale of two Egypts. On one hand, the gleaming, orderly, and exclusive NAC; on the other, an old Cairo potentially left behind, still grappling with its immense challenges but now stripped of its status as the nation’s political center. What happens to the social fabric when a country’s elite inhabits a separate, purpose-built reality?

The Challenge of Water

A critical physical geography challenge looms over the entire project: water. Building a city for a planned 6.5 million people, complete with a massive green park, in the middle of one of the world’s most arid regions is a monumental hydrological undertaking. The NAC will rely on water piped from the Nile, a river whose resources are already intensely contested, most notably in the ongoing dispute with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). The capital’s thirst places yet another demand on a water source that is fundamental to Egypt’s very existence.

An Audacious Gamble on the Future

Egypt’s New Administrative Capital is a geographical spectacle—an attempt to defy the constraints of history, terrain, and demographics. It is both a pragmatic response to the urban crisis of Cairo and a grandiose projection of national power. It redraws the map of Egypt, shifting focus from the ancient valley to a new desert frontier.

Whether this gamble will pay off remains to be seen. Will it become a dynamic engine of a new Egyptian economy, or a hollow, gilded cage in the desert? The answer will have profound consequences, not just for the 22 million people of Cairo, but for the identity and future of the entire nation. It is a bold stroke on the map, and the world is watching to see how this new geography takes root.