These are the planet’s great closed-off drainage systems, where geography conspires to trap water inland. From the shimmering salt flats of North America to the deserts of Central Asia, these basins are unique landscapes forged by topography and climate, hosting ecosystems and human histories found nowhere else.

The Hydrology of No Escape

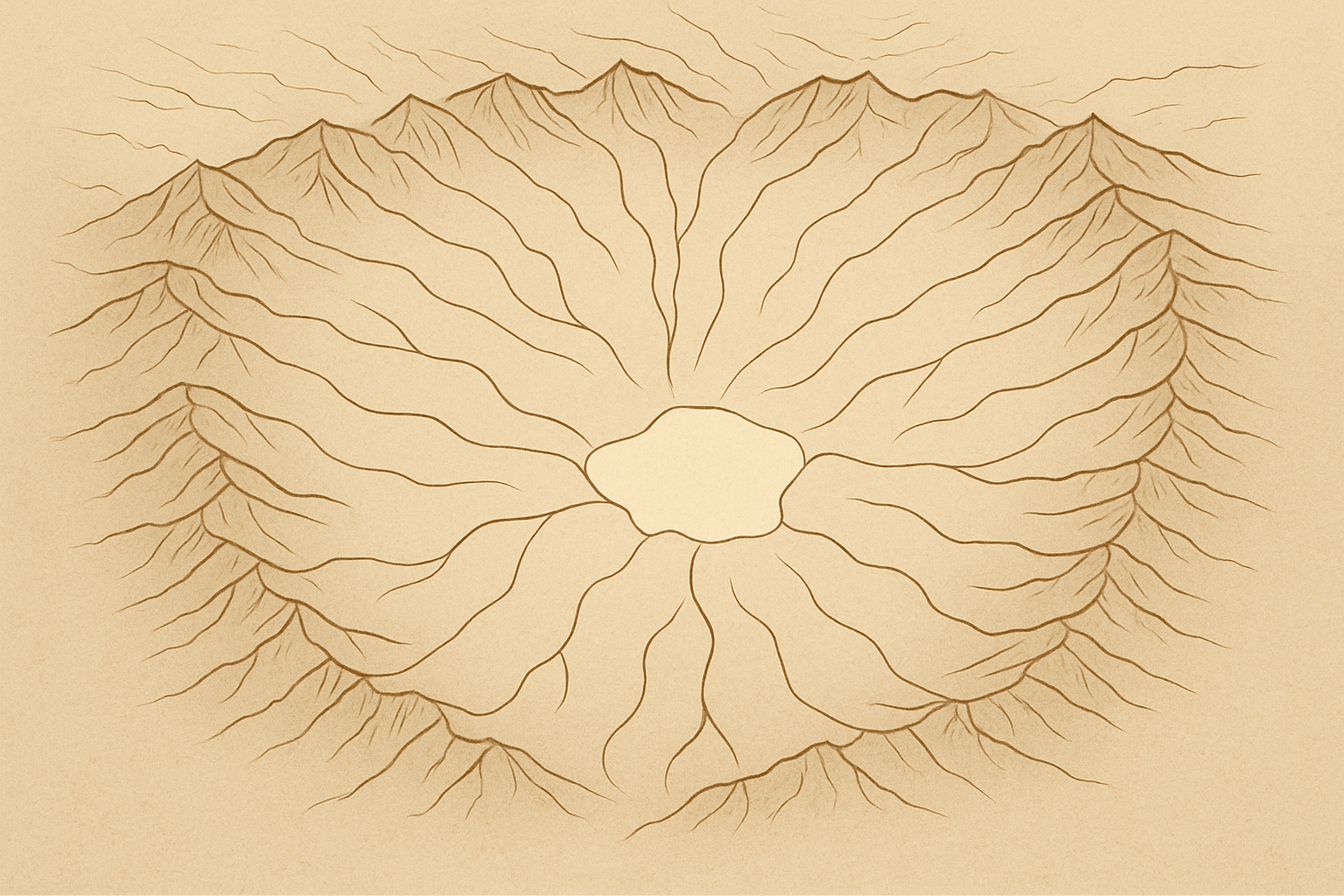

The term “endorheic” comes from Ancient Greek: éndon, meaning “within,” and rheîn, meaning “to flow.” It literally means “to flow within.” An endorheic basin is a closed watershed, a topographic bowl that doesn’t allow water to drain out to an external body like an ocean. Any precipitation that falls within the basin’s rim—whether as rain or mountain snowmelt—is destined to stay there.

This stands in stark contrast to the more common exorheic basins (like the Amazon or Mississippi river basins) that drain into the ocean. So, if water can’t flow out, where does it go? It has only two escape routes:

- Evaporation: In the arid or semi-arid climates where these basins are common, the sun is a relentless force. Water pools in the lowest point of the basin, forming lakes or wetlands, and evaporates back into the atmosphere.

- Seepage: Some water seeps down into the ground, recharging underground aquifers.

For an endorheic basin to form, two conditions are usually necessary: a topographic barrier like a ring of mountains, and an arid climate where evaporation rates are higher than precipitation rates. This is why they are often synonymous with the world’s great deserts and steppes.

A World of Salt: Unique Ecosystems

The constant process of evaporation has a profound effect on the chemistry of endorheic basins. As water evaporates, it leaves behind any dissolved minerals and salts it picked up on its journey from the mountains. Over millennia, these minerals accumulate, creating hypersaline environments.

This leads to the formation of iconic geographical features:

- Saline Lakes: Bodies of water far saltier than the ocean, such as the Great Salt Lake in Utah or the Dead Sea in the Middle East.

- Salt Pans or Playas: When a lake completely evaporates, it leaves behind a vast, flat crust of salt. The Bonneville Salt Flats in the US and the Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia (the world’s largest) are breathtaking examples.

- Brackish Marshes: On the fringes of these saline lakes, hardy, salt-tolerant plants called halophytes thrive, creating vital habitats.

Life here must be tough and specialized. These are realms of extremophiles—organisms adapted to extreme conditions. Brine shrimp and brine flies flourish in the salty water, providing a protein-rich food source for millions of migratory birds, such as flamingos, avocets, and phalaropes. The stark, seemingly lifeless landscape is, in fact, a crucial link in a global ecological chain.

A Tour of the World’s Great Basins

Endorheic basins cover roughly 18% of Earth’s land surface and are found on every continent. Let’s visit a few of the most significant.

The Great Basin, USA

Covering nearly all of Nevada and parts of Utah, California, Oregon, and Idaho, the Great Basin is a classic example of “basin and range” topography. North-south trending mountain ranges are separated by flat, arid valleys or basins. Its most famous feature is the Great Salt Lake, a remnant of the immense prehistoric Lake Bonneville. The basin also contains Death Valley, the lowest, driest, and hottest area in North America. For humans, it was a formidable barrier for 19th-century pioneers, and today its major cities, Salt Lake City and Reno, grapple with managing water resources in an ever-drier climate.

The Tarim Basin, China

Dominated by the formidable Taklamakan Desert and encircled by some of the world’s highest mountain ranges—the Tian Shan, Kunlun, and Pamir mountains—the Tarim Basin in Northwest China is one of the most arid places on Earth. The Tarim River, fed by glacial melt, flows eastward across the desert, historically terminating in the wandering salt lake of Lop Nur. For centuries, oasis cities on the basin’s edge, like Kashgar and Turpan, were vital stops on the Silk Road. Today, it’s a region of immense geopolitical interest due to its resources and unique cultural heritage.

The Caspian Depression, Asia & Europe

The world’s largest endorheic basin is centered on the Caspian Sea, the largest inland body of water on Earth. So vast it feels like an ocean, the Caspian is technically a terminal lake, fed primarily by the Volga and Ural rivers flowing from the north. Bordered by five countries (Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Azerbaijan), the basin is a global hotspot for oil and natural gas production. Its famous sturgeon populations, the source of beluga caviar, are critically endangered due to overfishing and pollution, highlighting the pressures on these closed systems.

The Dead Sea Basin, Middle East

Shared by Israel, Jordan, and Palestine, this basin contains the Dead Sea, whose shores are the lowest land-based elevation on Earth, more than 430 meters (1,412 ft) below sea level. Its extreme salinity (over nine times saltier than the ocean) makes swimming more like floating. The Jordan River is its main tributary, but diversion of its water for agriculture and cities has caused the Dead Sea to shrink at an alarming rate.

A Fragile Balance: Human Impact and the Future

While beautiful and unique, endorheic basins are incredibly fragile. Because they are closed systems, they have no ability to flush out pollutants or replenish water lost to human activity. They are canaries in the coal mine for water mismanagement.

The most tragic example is the Aral Sea in Central Asia. Once the fourth-largest lake in the world, it was decimated in the 20th century when the Soviet Union diverted the two rivers that fed it to irrigate cotton fields. The sea shrank by 90%, leaving behind a toxic, salt-choked desert and a collapsed regional economy. It stands as a stark warning.

Today, similar pressures face basins worldwide. The Great Salt Lake is shrinking, threatening air quality as its exposed lakebed releases dust containing heavy metals. The Lake Chad Basin in Africa is a flashpoint for conflict as water scarcity intensifies. These “seas with no exit” are a powerful mirror, reflecting our choices about water. They teach us that in a closed system, every drop counts, and there is no “away” to throw things.