For decades, two powerful currents have been converging: plummeting fertility rates and soaring life expectancy. The “replacement rate” – the number of births per woman needed to maintain a stable population – is 2.1. No European Union country is near it. In nations like Spain and Italy, the rate hovers around a startling 1.2. This isn’t a future problem; it’s a present reality. For every child under six, Italy now has more than five people over 65. The result is a continent that is simultaneously getting older and, in many places, smaller.

Mapping the “Gray”: The Spatial Divide of a Continent

Europe’s aging isn’t happening uniformly. It has a distinct and telling geography, creating a patchwork of vibrant, youthful hubs and vast, depopulating “gray zones.”

The East-West Chasm

The demographic story is particularly stark in Central and Eastern Europe. Countries like Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania face a double blow: rock-bottom birth rates combined with massive out-migration of their young and ambitious. Since joining the EU, millions have moved west in search of better opportunities, a phenomenon often called “demographic exsanguination.” This leaves behind an aging population, a shrinking workforce, and a landscape dotted with ghost villages and underfunded public services. The result is a cycle of decline that is incredibly difficult to break.

The Urban-Rural Split

Perhaps the most visible geographical impact is the growing divide between Europe’s cities and its countryside.

- The “Emptying” Interior: Vast swathes of Europe’s interior are hollowing out. Think of España Vaciada (“Empty Spain”), the rural Mezzogiorno in Southern Italy, or former East German states like Saxony-Anhalt. Young people leave for education and jobs in the cities, leaving their elders behind. This has a physical impact on the landscape. Fields go untilled, farmhouses crumble, and the main streets of once-thriving towns are lined with shuttered shops. The very fabric of rural life frays as schools, post offices, and clinics close down.

- Cities as Youth Magnets: In contrast, major metropolitan areas like Berlin, Paris, London, and Stockholm act as demographic magnets. They attract young professionals, students, and immigrants, creating dynamic, multicultural hubs. Yet, even here, the illusion of youth is thin. The high cost of living, especially for housing, often forces young families to delay having children or have fewer than they would like, contributing to the low national fertility rates.

The Economic Tremors: Pensions and Labor Pains

A map of Europe’s demography is also a map of its future economic challenges. With fewer people of working age to support a growing number of retirees, the continent’s famed social welfare models are under immense strain.

The Pension Predicament

Most European pension systems are “pay-as-you-go”, meaning today’s workers pay for today’s retirees. This social contract works perfectly in a classic population pyramid with a broad base of young people. But Europe’s pyramid is inverting, becoming top-heavy. The worker-to-retiree ratio is plummeting.

This is the source of intense political friction. France’s recent, explosive protests over raising the retirement age from 62 to 64 are a direct consequence of this demographic math. Governments across the continent face an impossible choice: raise taxes, cut pension benefits, or make people work longer. None of these options are politically popular.

The Great Labor Shortage

Beyond pensions, a shrinking workforce means a shortage of labor. Germany, Europe’s economic engine, is a prime example. It needs hundreds of thousands of new workers each year to fill gaps everywhere, from skilled engineers and IT specialists to truck drivers and elder-care nurses. This economic necessity is forcing a continent, parts of which are deeply skeptical of immigration, to actively recruit people from abroad.

The Contentious Answer: The Geography of Replacement Migration

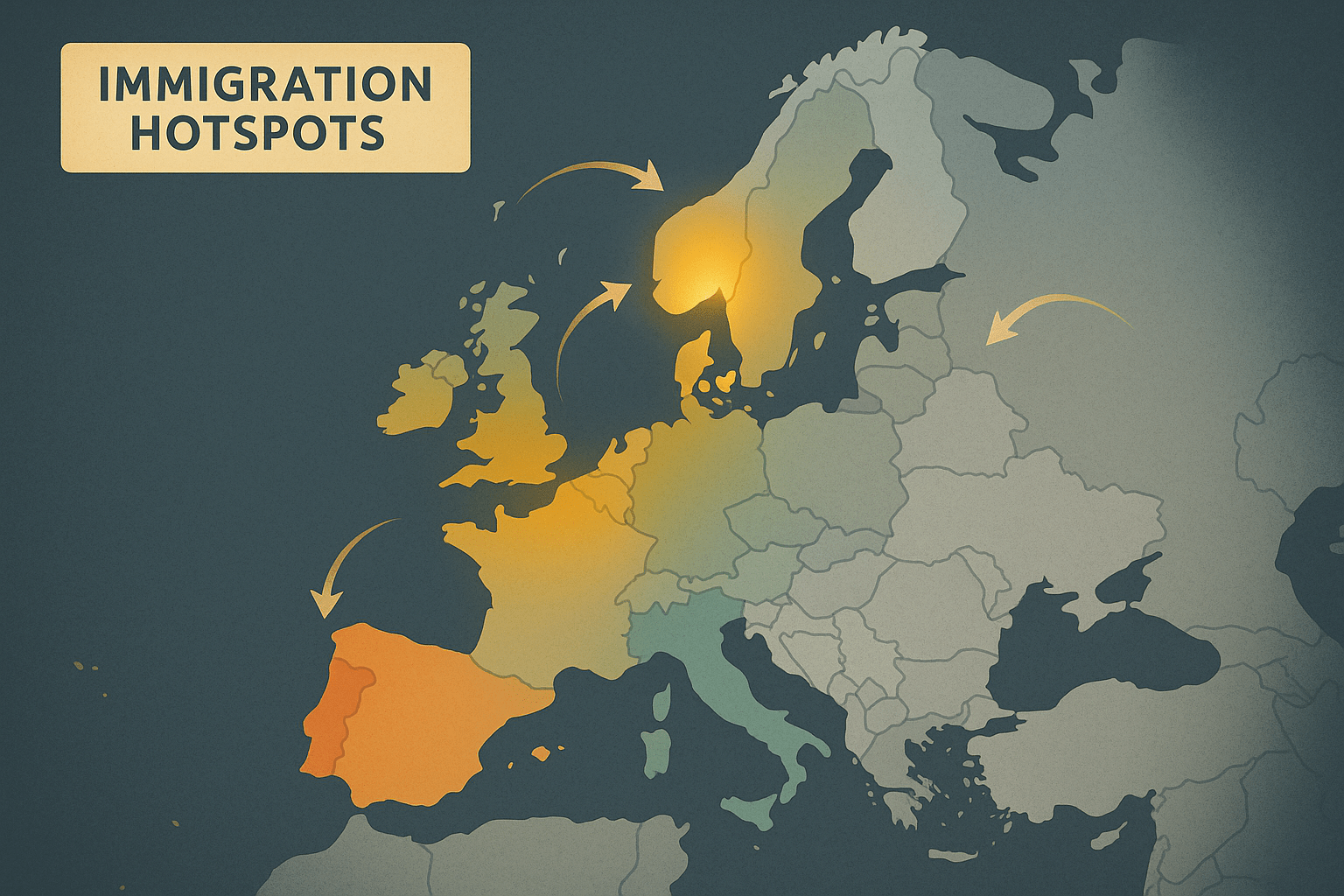

If a population isn’t replacing itself through birth, the only other way to prevent economic stagnation and demographic collapse is through immigration. This reality, often termed “replacement migration”, sits at the heart of Europe’s most volatile political debates.

The geography of this migration is clear. People flow from North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia—as well as from Eastern Europe—to the economic cores of Western and Northern Europe. They are not just seeking refuge but are pulled by the powerful magnet of labor demand.

This has created a profound political tension. On one hand, there is the pragmatic, economic need for migrants. On the other, there is a powerful cultural and political backlash, fueling the rise of nationalist and populist parties from Sweden to Italy. These movements often campaign on platforms of restricting immigration, tapping into fears about national identity, integration, and security.

The spatial dimension is critical here too. Immigrant communities often concentrate in specific urban neighborhoods, creating vibrant multicultural zones but also, at times, social friction and challenges for integration. The physical and social landscape of cities like Malmö, Marseille, and Brussels is being transformed by these global flows.

A Continent at a Crossroads

Europe’s demographic time bomb is not a distant threat; its ticking is the sound of life in a quiet Spanish village, the roar of protest on a Parisian boulevard, and the heated debates in the German Bundestag. It is a geographic story written across the continent—in the abandoned farms of the east, the strained public services of the south, and the politically charged suburbs of its western cities.

How Europe navigates this new reality will define its 21st-century identity. It is a challenge that pits economic necessity against political ideology and forces a deep reckoning with what it means to be European in an era of unprecedented demographic change.