Exploring these accidental wildernesses offers a powerful lesson in ecological resilience and succession. From vast, disaster-stricken exclusion zones to the quiet decay of a single city block, the return of nature follows a surprisingly predictable, yet endlessly complex, pattern.

The Geography of Abandonment

Before nature can return, humans must first leave. The human geography behind urban abandonment is as varied as the landscapes it creates. Broadly, these feral spaces are born from three circumstances:

- Sudden Catastrophe: These are the most dramatic examples. The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine, rendered uninhabitable by the 1986 nuclear disaster, is the archetype. A similar, though smaller-scale, process is underway around the Fukushima Daiichi plant in Japan. Natural disasters can have the same effect; the town of Plymouth on the island of Montserrat remains largely buried in volcanic ash, a modern-day Pompeii being slowly consumed by tropical vegetation.

- Gradual Decline: More common are the slow-motion abandonments caused by economic and demographic shifts. The deindustrialization of America’s Rust Belt, for example, left cities like Detroit with vast tracts of vacant land. As factories closed and people moved away, entire neighbourhoods emptied, creating a unique mosaic of inhabited homes, derelict buildings, and fledgling urban prairies.

- Political Stalemate: Sometimes, human conflict creates an unintentional nature preserve. The “Green Line” that divides Cyprus has left the resort town of Varosha a ghost city since the 1974 invasion. Once a bustling tourist hub, its hotels and boulevards are now being silently dismantled by salt, wind, and pioneer plants, while its deserted beaches have become vital nesting grounds for endangered sea turtles.

The Process of Re-Wilding: An Ecological Timetable

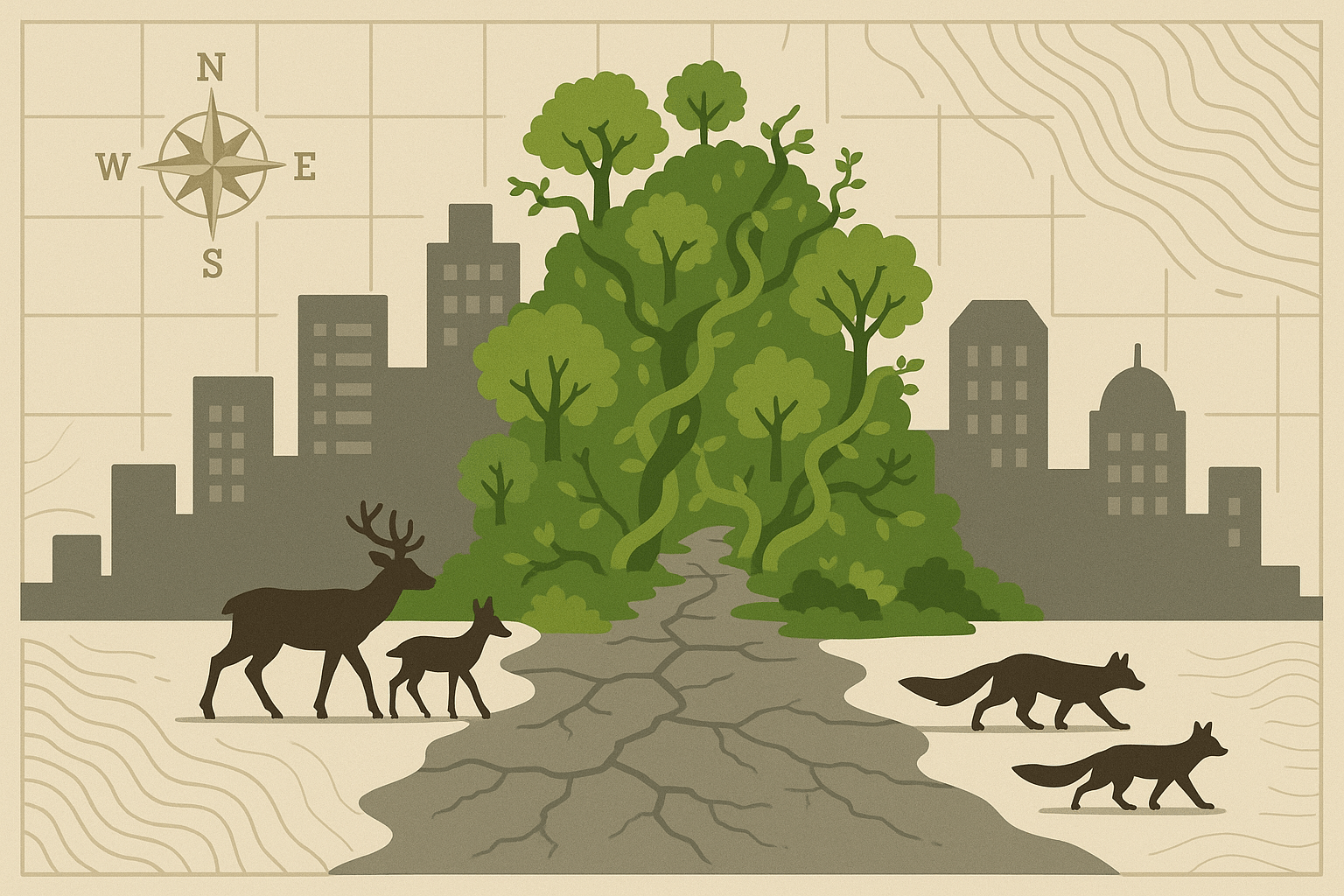

Regardless of the cause, once human maintenance ceases, ecological succession begins its work. This process unfolds in predictable stages, transforming the built environment into a novel ecosystem.

Stage 1: The Pioneers (Years 1-5)

The first responders are hardy, opportunistic species. Weeds like dandelion and thistle, grasses, and mosses are masters of colonizing disturbed ground. They exploit the smallest cracks in asphalt and concrete, their roots subtly widening the fissures. In Europe, the buddleia, or “butterfly bush”, is so effective at colonizing rubble and railway lines it’s often called the “bombsite plant.” These pioneers begin the crucial work of creating soil, trapping dust and organic matter, and paving the way for what’s next.

Stage 2: The Colonizers (Years 5-25)

As soil deepens, fast-growing, sun-loving trees take root. Species like birch, poplar, willow, and the invasive Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) form the first wave of woodland. Their seeds, carried by wind, find purchase on rooftops, in gutters, and on vacant lots. The urban structure is repurposed: building ledges become cliffs for nesting kestrels, and crumbling basements serve as dens for foxes and raccoons. The city’s grid begins to blur under a green canopy.

Stage 3: The Climax Community (Decades to Centuries)

Over a much longer timescale, slower-growing, shade-tolerant trees like oak, maple, and beech begin to rise. They eventually outcompete the fast-growing pioneers, creating a more stable, mature forest. The evidence of the city won’t vanish entirely; it becomes a ghost in the landscape. The flat topography of former parking lots, the linear corridors of old roads, and the altered chemistry of the soil will influence the forest’s structure for centuries to come.

Case Studies in Feral Geography

Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Ukraine

Thirty years after the nuclear accident, the 2,600-square-kilometer Zone is Europe’s most famous accidental wilderness. The absence of humans has been a greater boon for wildlife than the radiation has been a detriment. Populations of apex predators like wolves and Eurasian lynx are thriving. The release of endangered Przewalski’s horses has been a success, and there are even signs of brown bears returning. The ghost city of Pripyat is a haunting forest, with trees pushing through the floors of apartments and a thick carpet of moss covering what was once the central square. It’s a living laboratory for studying long-term radiation effects and large-scale ecological succession.

Detroit, USA

Detroit presents a different model: the “patchwork” feral city. Here, abandonment isn’t absolute but scattered across the urban fabric. Decades of economic decline resulted in over 100,000 vacant lots, creating a unique urban prairie. These green spaces exist alongside vibrant communities, leading to a complex human-nature interface. Pheasants dart across decaying streets, and red foxes have become established residents. While presenting challenges, this “greening” has also prompted innovation, sparking a robust urban agriculture movement as residents transform vacant lots into productive community gardens and farms.

A New Urban Ecosystem

It’s crucial to understand that these feral cities are not a return to a pristine, pre-urban wilderness. They are entirely new, “novel ecosystems” shaped by their anthropogenic origins.

The physical geography is permanently altered. Impermeable surfaces like roads and foundations create unnatural drainage patterns, leading to localized wetlands and ponds. The soil is a cocktail of rubble, brick, and industrial contaminants like heavy metals, which can dictate which plant species thrive and which fail. The very buildings that remain create unique habitats—vertical cliffs, sheltered caves, and sun-baked plains—that don’t exist in a natural forest, attracting species like peregrine falcons that are perfectly adapted to such structures.

These reclaimed lands force us to reconsider our relationship with nature and the city. They demonstrate nature’s incredible power of resilience, but they are also monuments to human tragedy, economic failure, or conflict. They stand as a powerful, living reminder that our cities are not separate from the natural world, but a part of it. When we step away, the wild is always waiting to step back in.