The Mapmaker’s Ghost: Hunting for Cartography’s Copyright Traps

Imagine you’re driving through the rolling hills of upstate New York, following an old paper map. You’re looking for a small town called Agloe, a place marked clearly at a specific intersection. But when you arrive, there’s nothing there. No houses, no post office, just a dirt road crossroads. You might assume your map is simply old and wrong. But what if the town was never meant to be there at all? What if it was a phantom, a ghost placed on the map for a very specific purpose?

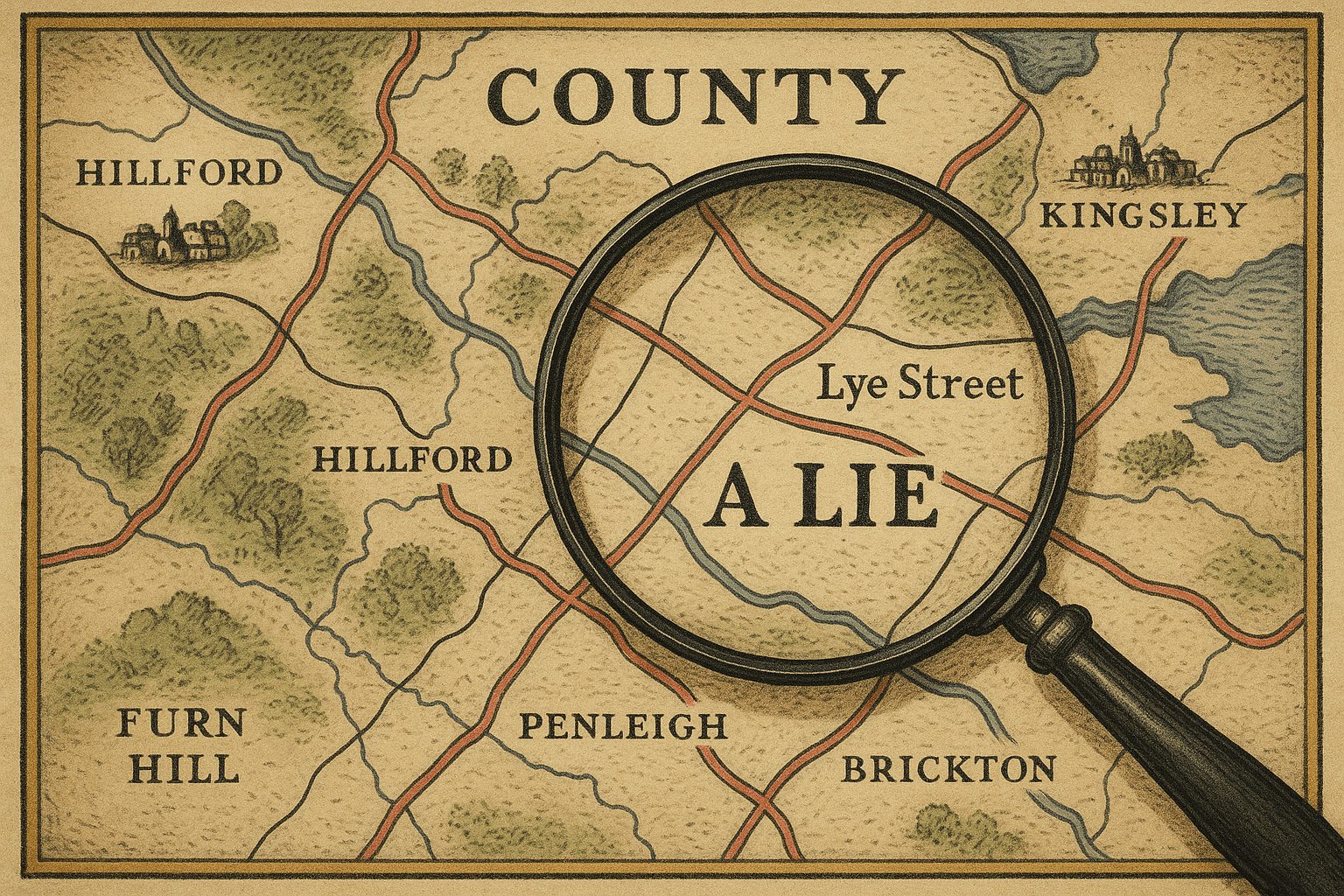

Welcome to the fascinating and secretive world of “fictitious entries”, one of cartography’s cleverest traditions. For centuries, mapmakers have faced a fundamental problem: their work, which often requires immense effort, expensive surveys, and artistic skill, is incredibly easy to copy. To protect their intellectual property, they developed an ingenious defense mechanism: they would deliberately insert a small, harmless error into their maps. This could be a fake street, a non-existent town, or even a phantom mountain peak. These are known as copyright traps, paper towns, or trap streets, and they serve as a cartographer’s unique fingerprint.

Why Weave a Web of Lies? The Cartographer’s Dilemma

Creating an accurate map is a monumental task. It involves compiling data from surveys, satellite imagery, and on-the-ground reports. It requires meticulous drafting, precise labeling, and an eye for design. Before digital tools, this was all done by hand, representing thousands of hours of labor. If a rival publisher simply photocopied the map and sold it as their own, how could the original creator prove the theft?

This is where the fictitious entry comes in. You can’t copyright facts—the existence of London or the height of Mount Everest is public knowledge. However, you can copyright the unique expression of those facts. By adding a tiny, made-up detail, the mapmaker creates something wholly original. If that same fake detail—that “trap street”—appears on a competitor’s map, it’s undeniable proof of plagiarism. The copier can’t claim they independently surveyed the area and “discovered” the same non-existent place. It’s the cartographic equivalent of a smoking gun.

A Gazetteer of Ghosts: Famous Fictitious Entries

These cartographic phantoms are hidden all over the world, and some have developed fascinating stories of their own. Here are a few of the most notable examples:

Agloe, New York

Perhaps the most famous paper town of all, Agloe, New York, was created in the 1930s by the General Drafting Company for its Esso gas station maps. The founders, Otto G. Lindberg and Ernest Alpers, combined their initials to form the name (AGLOE). They placed their fictional hamlet at a dirt-road intersection in the Catskill Mountains. Decades later, when Rand McNally released a map also featuring Agloe, General Drafting cried foul. But Rand McNally had a surprising defense: they claimed the place was real. It turned out that someone had seen Agloe on the popular Esso map, bought the property at the “location”, and built a small general store, naming it the Agloe General Store. A fiction, created as a copyright trap, had willed itself into a brief, fragile existence.

Trap Streets of London

In the dense, labyrinthine streets of London, it’s easy to believe a map could have a few errors. Mapmakers have long taken advantage of this. The creators of the iconic London A-Z map book, Geographers’ A-Z Map Company, were famously protective of their work. For years, they were rumored to have included over 100 trap streets in their publications. These weren’t grand avenues but often tiny, dead-end alleys or slightly misdrawn laneways, just enough to catch a lazy competitor. One such confirmed example was a short dead-end street named “Bartlett Place”, which existed only in the pages of their map book.

Mount Richard, Colorado

It’s not just towns and streets. Even physical geography can be a source of fiction. In the 1970s, a draftsman for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) working on a map of the Rockies in Colorado quietly added a new peak and named it “Mount Richard.” This was not a copyright trap in the commercial sense but an act of personal tribute to a colleague. For two years, Mount Richard existed on official government maps until a diligent checking process uncovered the phantom peak and scrubbed it from the record.

Beatosu and Goblu, Ohio

Sometimes, these traps are just for fun. In the late 1970s, the official state highway map of Michigan included two fictional towns in northern Ohio: Beatosu and Goblu. This was a playful jab from a University of Michigan alumnus on the map’s committee, referencing the fierce football rivalry with Ohio State University (“Beat OSU” and “Go Blue!”). The towns were eventually removed, but they live on in cartographic folklore as a classic example of mapmaker mischief.

Fictitious Entries in the Digital Age

You might think that in the era of Google Maps, Waze, and GPS, these cartographic ghosts would be a thing of the past. But the problem of data theft is more rampant than ever. While blatant paper towns are less common on major digital platforms, the practice of embedding copyright traps continues in more subtle forms.

Instead of a whole town, a digital trap might be:

- A slightly incorrect street curvature.

- A business that is deliberately mislabeled.

- An incorrect or non-existent house number.

- A slightly altered spelling of a minor landmark.

A curious case is that of Argleton, a phantom settlement in West Lancashire, UK, that appeared on Google Maps for years before being removed in 2009. It was located in an empty field, leading to widespread speculation. Was it a copyright trap? A simple data-entry error? A glitch in an algorithm? Google never confirmed, but the mystery of Argleton shows that even our digital world has its share of ghost places.

The Enduring Allure of the Map’s Secrets

Fictitious entries remind us that a map is not a perfect, objective mirror of reality. It is a human creation—a story told by a cartographer. These phantoms are a testament to the creator’s pride, their legal cunning, and sometimes, their sense of humor. They are the secret signatures left behind to guard the work. So the next time you’re navigating, whether with a creased paper map or a glowing screen, and you find a detail that doesn’t quite match the world around you, take a moment. You may have just stumbled upon a ghost in the machine, a mapmaker’s clever trap lying in wait.