The Human Geography of a Hole in the Ground

A tunnel is never just a hole. It is a direct response to the human geography of a border. When a political line is drawn across a landscape, it creates a gradient—a sharp difference in economic conditions, legal status, and access to goods. This gradient is the engine of smuggling. The greater the disparity and the more fortified the border, the more incentive there is to go under it.

This phenomenon is starkly illustrated in two of the world’s most tunneled regions:

- The U.S.-Mexico Border: Here, the primary driver is the immense demand for narcotics in the United States and, to a lesser extent, the movement of people. The border separates one of the world’s wealthiest consumer markets from key drug production and transit countries. This powerful economic pull justifies the immense cost and risk of constructing sophisticated tunnels.

- The Gaza-Egypt Border: Along the “Philadelphi Corridor” separating the Gaza Strip from Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, tunnels became a lifeline. In response to a long-term blockade, a subterranean economy boomed. These tunnels were used to smuggle everything from essential foodstuffs, fuel, and medicine to livestock, consumer goods, and, notoriously, weapons and militants. They were a direct geographical adaptation to a state of siege.

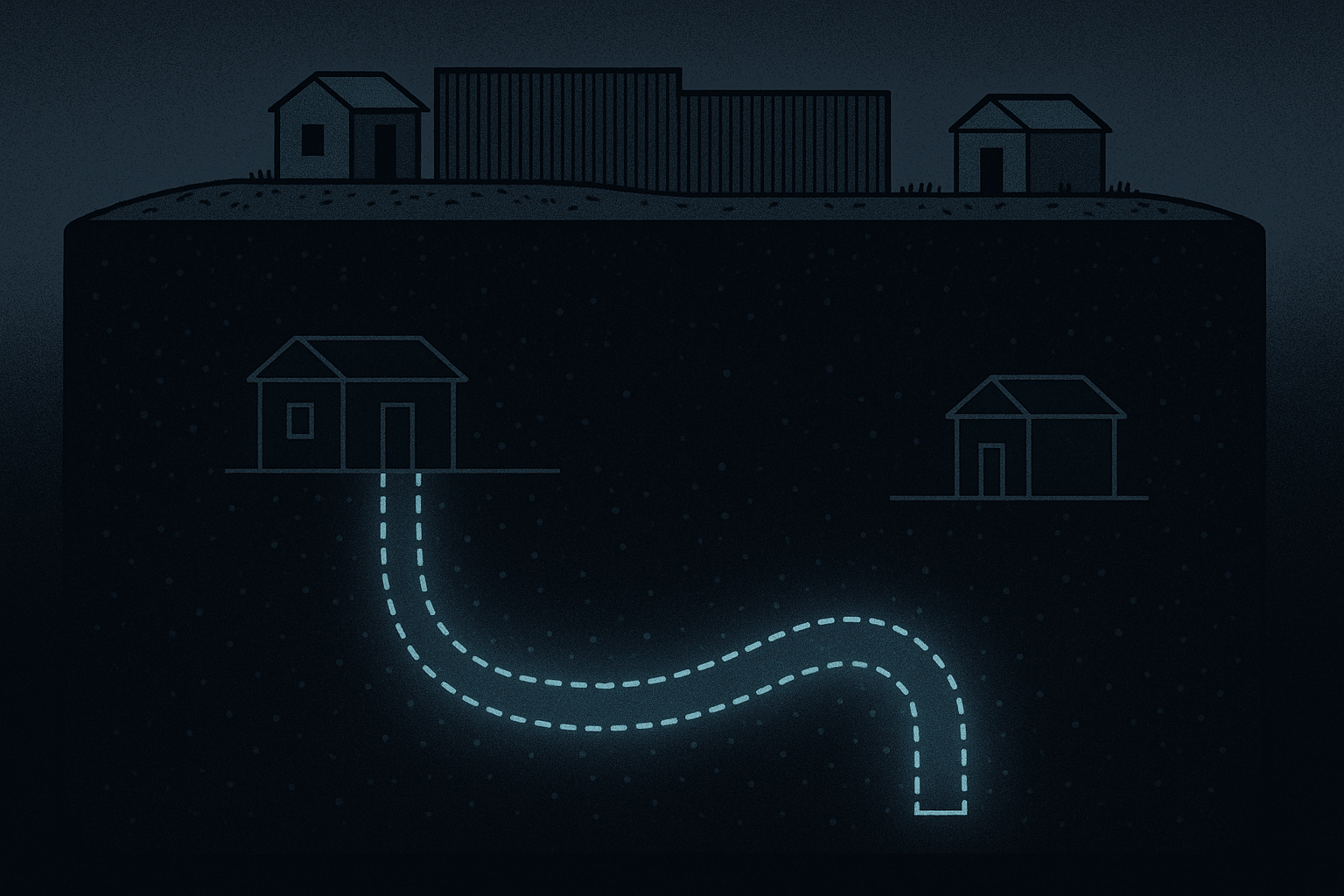

In both cases, the tunnels are not randomly placed. Their entrances and exits are strategically located within the human landscape—hidden in the basements of homes in the dense urban sprawl of Rafah or concealed beneath the floors of nondescript warehouses in the bustling industrial parks of Tijuana and San Diego’s Otay Mesa district.

The Physical Landscape: Digging In

While human factors determine the *why* and *where* of a tunnel, physical geography dictates the *how*. The very earth beneath the border is a critical variable, making some areas ripe for tunneling and others nearly impossible.

Soil, Sand, and Granite

The ground itself is the first and most important challenge. The geology of a border region can either be a tunneler’s best friend or worst enemy.

In the San Diego-Tijuana sector, a significant portion of the border sits atop the Otay Formation. The soil here often includes a layer of soft, clay-like material known as bentonite. This soil is ideal for illicit construction: it’s soft enough to be excavated with relative ease using shovels and pneumatic tools, but stable enough to hold its shape and reduce the risk of collapse. This geological advantage is a primary reason why this specific corridor is the epicenter of the most sophisticated “super tunnels.”

Contrast this with the border in Arizona, where smugglers must contend with solid rock and mountainous terrain. Tunneling through granite is an arduous, expensive, and loud process requiring heavy machinery or explosives, making it a far less common tactic.

In Gaza, the geography presents a different set of problems. The coastal terrain is composed of loose, shifting sand. While easy to dig, it is incredibly unstable. Tunnels here are prone to collapse, making them perilous death traps. To compensate, they must be heavily reinforced with wooden planks or concrete panels, and are often dug at shallower depths, making them more vulnerable to detection. Furthermore, the high water table of the coastal plain is a constant threat, requiring pumps to prevent flooding.

A Tale of Two Tunnels

The resulting tunnels are products of their unique geographical and political environments.

The U.S.-Mexico “super tunnel” is a marvel of illicit engineering. Often running for over half a mile at depths of 60-90 feet to evade seismic sensors, they are equipped with ventilation systems, electrical lighting, water pumps, and even rail systems to transport tons of cargo efficiently. One tunnel discovered in 2020 stretched for three-quarters of a mile and featured an elevator at its entrance.

The typical Gaza-Egypt tunnel, by contrast, was often a cruder, more desperate affair. Narrow, claustrophobic, and barely tall enough for a person to crawl through, they were dug by hand in perilous conditions. Yet, for years, hundreds of these tunnels formed a complex, interwoven network that sustained an entire economy.

The Cat-and-Mouse Game: Mapping the Subterranean

For every tunneler, there is a tunnel hunter. Border security agencies are engaged in a constant technological and intelligence battle to map this hidden geography.

The U.S. Border Patrol’s multi-agency “Tunnel Task Force” employs a range of geographical tools:

- Seismic Sensors: These devices listen for the subtle vibrations caused by digging, but their effectiveness is limited by ambient noise from cities and highways, and the type of soil they are placed in.

- Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR): GPR sends radio waves into the ground to detect anomalies and voids. However, its success is highly dependent on soil conditions. Dense clay, moisture, and rock layers can scatter or block the signals, limiting its depth and clarity.

- Acoustic Methods: By thumping the ground and listening to the returning sound waves, agents can sometimes identify hollow areas.

Often, technology is secondary to human intelligence and old-fashioned observation. A tip-off from an informant or an agent noticing a suspicious amount of dirt being hauled away from a warehouse can be the key to discovery.

Counter-tunneling can also have profound geographical consequences. In an effort to destroy the Gaza network, Egyptian authorities began flooding the tunnels with seawater. This not only collapsed the tunnels but had a devastating environmental impact, contaminating the fresh groundwater aquifer that Gaza’s population depends on for agriculture and drinking water—a permanent scar on the physical geography of the region.

A World Beneath

Smuggling tunnels are more than just criminal infrastructure; they are a powerful symbol of the limitations of surface-level control. They represent a dynamic, underground geography that adapts, innovates, and persists in the face of immense pressure.

As long as stark political and economic divides are drawn across the earth, there will be those who seek to cross them. And where walls rise higher and fences grow thicker, human ingenuity will continue to look down, proving that the map of our world has a secret, vital, and ever-changing layer hidden right beneath our feet.