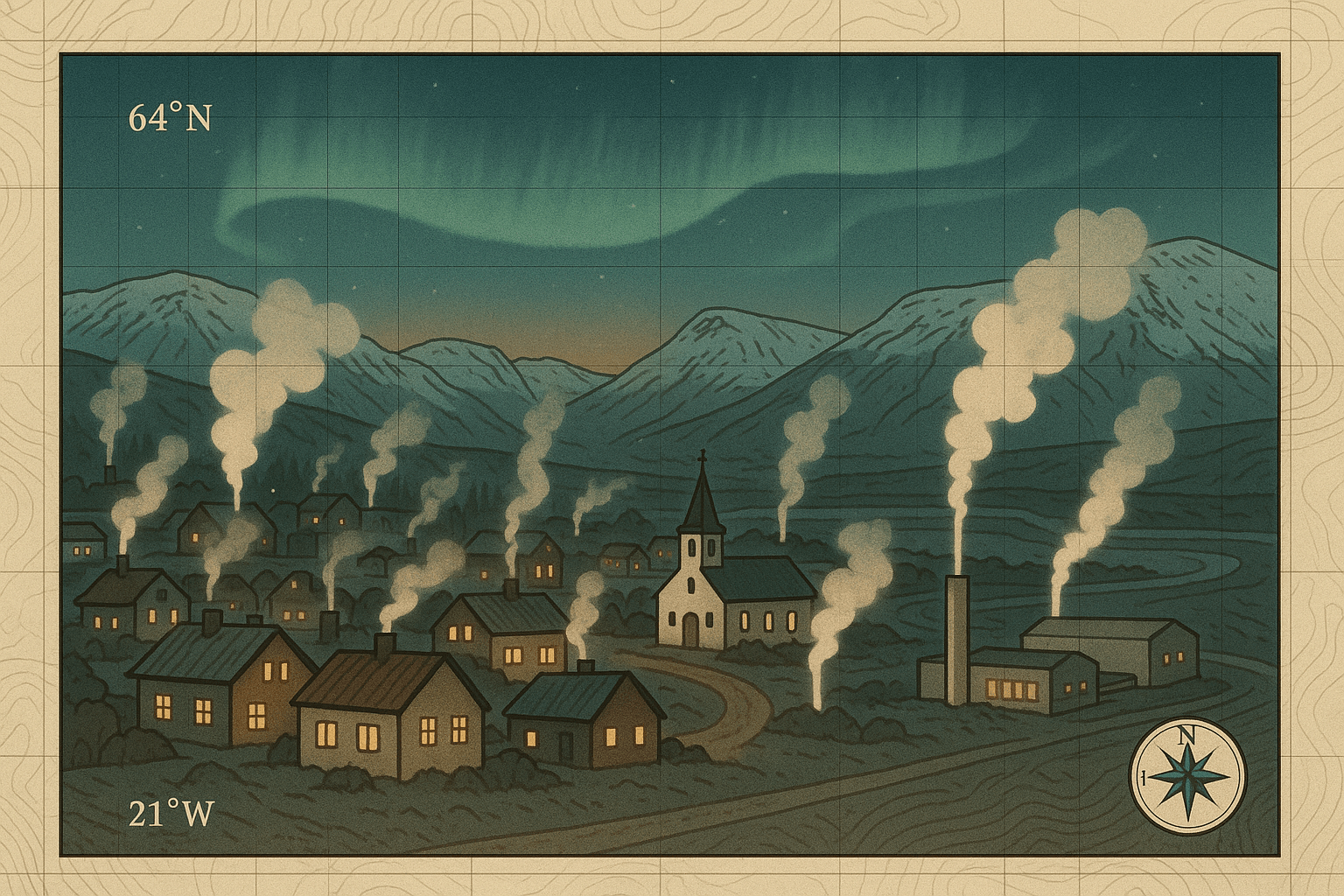

Imagine your morning shower is heated directly by the Earth’s core. Picture walking down a city street in the dead of winter, not on icy pavement, but on a sidewalk kept clear by warmth radiating from below. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the daily reality for residents of geothermal towns, communities built in the planet’s most volcanically active zones. These unique settlements, from the frosty landscapes of Iceland to the lush islands of New Zealand, offer a masterclass in human adaptation, turning a potentially destructive force into a source of life, energy, and culture.

The Geography of Heat: Living on the Edge

To understand geothermal towns, you first need to understand the powerful physical geography churning beneath them. The Earth’s crust isn’t a solid shell; it’s a jigsaw puzzle of massive tectonic plates that are constantly shifting. The most intense geothermal activity occurs at the boundaries of these plates.

Most of these “hot spots” are located along the infamous Pacific Ring of Fire, an arc of intense seismic and volcanic activity stretching around the Pacific Ocean. Here, oceanic plates are forced beneath continental plates (a process called subduction), creating immense friction and melting rock into magma. In other places, like Iceland, the plates are actively pulling apart, allowing magma to rise closer to the surface along a divergent boundary known as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

In these geologically privileged locations, the heat from magma chambers is so close to the surface that it superheats underground water reservoirs. This creates a wealth of geothermal phenomena:

- Hot Springs: Groundwater heated by magma that rises to the surface.

- Geysers: A type of hot spring where water is trapped in underground channels, builds up pressure, and erupts violently.

- Fumaroles: Vents in the Earth’s crust that release steam and volcanic gases like sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide.

- Mud Pots: Hot springs with limited water that mix with surrounding soil and rock to create bubbling pools of mud.

It is this collection of natural plumbing that geothermal communities tap into, harnessing the planet’s internal furnace for human use.

Case Study: Iceland – The Land of Fire, Ice, and Steam

Nowhere is geothermal living more integrated into national identity than Iceland. Sitting directly atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the country is a geographical marvel of glaciers and volcanoes coexisting. This unique position means that geothermal energy is not just a novelty; it’s the backbone of the nation.

Nearly 90% of all Icelandic homes are heated by geothermally warmed water, piped directly into radiators. In the capital, Reykjavík, this system has a fascinating side effect: a network of pipes running under major streets and sidewalks keeps them free of snow and ice all winter, a clever piece of human geography responding to a physical one. The city’s famous outdoor swimming pools, or sundlaugs, are popular year-round, offering a warm, communal gathering place even during a blizzard.

Just a short drive from the capital is the town of Hveragerði, often called the “Hot Spring Town.” Here, the geothermal activity is so apparent that steam rises from cracks in the ground right in people’s backyards. Residents have famously used these natural steam vents to bake bread, burying a pot of dough in the hot earth for 24 hours. More commercially, the abundant and cheap geothermal heat powers vast complexes of greenhouses, allowing Iceland, a subarctic nation, to grow its own tomatoes, cucumbers, and even bananas.

Case Study: New Zealand – The Work of Rūaumoko

On the other side of the world, in the heart of the Pacific Ring of Fire, New Zealand’s North Island is a hub of geothermal power. The Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, have a deep cultural connection to this energy, which they call mahi a Rūaumoko (the work of the god of earthquakes and volcanoes).

The city of Rotorua is the epicenter of New Zealand’s geothermal life. The first thing a visitor notices is the unmistakable smell of sulfur in the air, a constant reminder of the power simmering below. Steam vents puff from city parks, gardens, and drainage ditches. For centuries, Māori communities have used the natural hot pools (waiariki) for bathing and healing, and the steam vents for cooking food in traditional earth ovens known as hāngī.

Today, this ancient tradition exists alongside modern industry. Rotorua harnesses geothermal steam not only to generate electricity and heat homes but also to power major industries like timber processing and pasteurizing milk. Living in Rotorua means embracing this geothermal reality, from enjoying a soak in a natural “hot tub” to contending with the corrosive effects of sulfuric gases on metal and electronics.

The Hot and Cold of Geothermal Living

Life in a geothermal town is a study in contrasts, a balance of incredible benefits and unique challenges.

The Benefits

- Sustainability: Geothermal is a reliable, 24/7 renewable energy source that drastically reduces a community’s carbon footprint and reliance on imported fossil fuels.

- Economic Perks: Extremely low heating costs for residents are a major advantage. The unique landscape also fuels a thriving tourism industry centered around spas, geysers, and volcanic parks like Iceland’s Blue Lagoon.

- Unique Lifestyle: The accessibility of natural hot springs, geothermally heated pools, and unique culinary traditions create a quality of life and cultural identity found nowhere else.

The Challenges

- Geological Risks: The very forces that provide the energy also pose a constant threat. Earthquakes are common, and the risk of volcanic eruption, while often low, is ever-present. Land can also subside as underground water is withdrawn.

- Environmental Management: While greener than fossil fuels, geothermal energy isn’t perfectly clean. The steam can bring trapped gases like carbon dioxide (CO₂) and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) to the surface. Modern power plants work to re-inject these gases back underground, but careful management is essential.

- Infrastructure Demands: Building a geothermal power plant and a district heating system requires a huge initial investment. Furthermore, the minerals and gases in geothermal fluids are highly corrosive, meaning pipes and equipment require constant maintenance and replacement.

A Blueprint for a Hotter Future?

Geothermal towns are more than just geographical oddities; they are living laboratories. They demonstrate a profound partnership between humanity and the planet’s raw power. By embracing the heat beneath their feet, communities in Iceland, New Zealand, and other geothermally active regions like Italy and Japan have created secure, sustainable, and truly unique ways of life. As the world searches for cleaner energy sources, the lessons learned from living on a volcano may just provide a blueprint for a warmer, more resilient future.