In the digital glow of our interconnected world, our devices feel clean, abstract, and almost weightless. A smartphone, a laptop, a television—they are portals to information and entertainment. But what happens when they break, become obsolete, and are discarded? For a staggering volume of the world’s electronic waste, or e-waste, the final destination is a real, physical place with a name: Agbogbloshie, a suburb of Accra, the capital city of Ghana.

Often mislabeled as the “world’s largest e-waste dump”, Agbogbloshie is something far more complex. It’s a vibrant, informal industrial ecosystem, a place of immense human ingenuity and economic survival, built upon a geography poisoned by the toxic afterlife of our global consumption. To understand Agbogbloshie is to map a landscape where global trade routes, human migration, and environmental chemistry collide.

From a European Suburb to a Ghanaian Lagoon

The journey of a discarded computer to Agbogbloshie reveals the troubled geography of global trade. It often begins in the Global North—a home or office in Europe or North America. The device is dropped off at a recycling center or a charity donation bin with the best of intentions. However, the high cost of safely dismantling and recycling electronics in developed nations creates a powerful economic incentive for exportation.

Circumventing international treaties like the Basel Convention, which restricts the movement of hazardous waste, containers filled with defunct electronics are often labeled as “used goods” or “donations.” Shipped across the Atlantic, they arrive at Ghana’s main industrial port, Tema. From there, trucks haul the containers inland to Accra, where merchants at the Agbogbloshie market pick through the items. What is salvageable may be repaired and sold. The vast remainder—broken, obsolete, and worthless as whole units—is moved to the scrapyard on the banks of the Korle Lagoon. This is where its transformation from a consumer product to a source of raw, hazardous material begins.

The Spatial Anatomy of a Scrapyard

Far from being a chaotic pile of junk, Agbogbloshie is a highly organized space, its geography dictated by the processes of recycling. The landscape is zoned by function, creating a spatial assembly line of deconstruction:

- The Periphery – The Marketplace: Here, older, more established workers repair and sell functional or semi-functional parts—keyboards, monitors, hard drives—in small stalls.

- The Dismantling Zone: Deeper inside the yard, young men and boys, many of them migrants from Ghana’s impoverished northern regions, constitute the primary labor force. Using stones, crude hammers, and their bare hands, they smash open television sets, computer towers, and printers to extract valuable components like motherboards, power supplies, and aluminum casings.

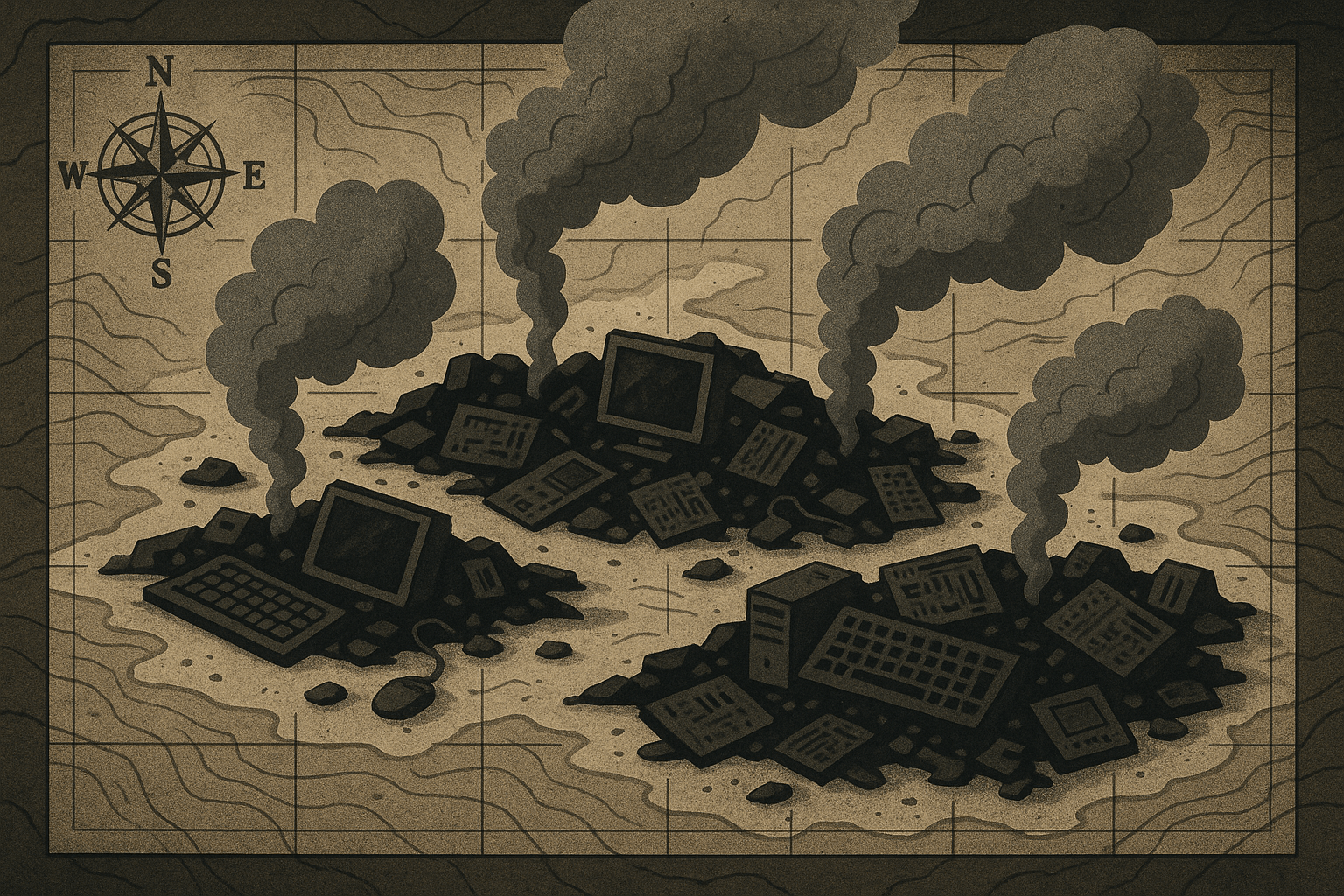

- The Burning Fields: This is the most infamous and visually stark zone of Agbogbloshie. Piles of insulated wires, cables, and plastic components are set ablaze. The goal is to melt away the plastic insulation to get to the valuable copper and aluminum within. Thick, acrid plumes of black smoke constantly billow into the sky, creating a hellish, ever-present haze.

- The Trading & Weighing Area: Once extracted and separated, the metals are taken to middlemen who weigh the scraps on scales and pay the workers. This material then moves up the supply chain, eventually sold to larger scrap dealers.

This spatial organization reflects a clear economic and social hierarchy, all unfolding on a landscape that bears the deep scars of these activities.

A Toxic Geography

The recycling processes at Agbogbloshie have created what geographers call a “toxic geography”—a physical environment saturated with hazardous materials that profoundly impact land, air, and water.

The ground itself is a toxic repository. Years of dismantling have caused heavy metals to leech into the soil. Samples from Agbogbloshie have revealed alarmingly high levels of lead from cathode ray tubes, mercury from flat-screen monitors, cadmium from batteries, and brominated flame retardants from plastic casings. These contaminants create a permanent poison in the very earth the workers stand on.

The air is thick with pollutants from the open burning of plastics and wires. This process releases a cocktail of carcinogenic chemicals, including dioxins and furans, into the atmosphere. The black smoke isn’t just smoke; it is a visible aerosol of lead, tin, and other particulate matter, inhaled daily by the workers and residents of the surrounding slums.

Perhaps most tragically affected is the Korle Lagoon, which borders the scrapyard. Once a vital fishery and a source of recreation for Accra, the lagoon is now biologically dead in many parts. Toxic runoff from the scrapyard flows directly into its waters, which eventually empty into the Gulf of Guinea. The water is black and sludgy, choked with chemical waste and devoid of the life it once supported.

The Human Cost and the Global Connection

For the thousands of people who work here, Agbogbloshie is not an abstract environmental problem; it is a source of livelihood. A day of burning wires to collect a few kilograms of copper can earn a worker more than they could in a week of farming in their home village. It’s a rational economic choice made in the face of limited options. This choice, however, comes at a devastating personal cost. Workers report chronic nausea, headaches, skin burns, and severe respiratory problems. The long-term health consequences of daily exposure to such a toxic environment are catastrophic.

Crucially, the story doesn’t end in the ashes of Agbogbloshie. The copper, aluminum, and small amounts of gold recovered from the circuit boards re-enter the global commodities market. The scrap is consolidated by dealers and often shipped to foundries and smelters in countries like China and India. In this sense, Agbogbloshie is not an end point but a critical, informal link in a global circular economy. Raw materials that began their life in a mine in, perhaps, Chile or the DR Congo, were manufactured into a phone in Asia, used in Europe, and are now salvaged in Ghana to be sent back to Asia for manufacturing once more.

Agbogbloshie is a stark geographical lesson. It reminds us that there is no “away” when we throw things away. Our consumption habits in one part of the world create profoundly altered, often poisoned, landscapes in another. The sleek devices in our pockets are tied by an invisible thread to the smoky fields of Accra, a place that powerfully illustrates the complex, unequal, and often destructive geography of our modern world.