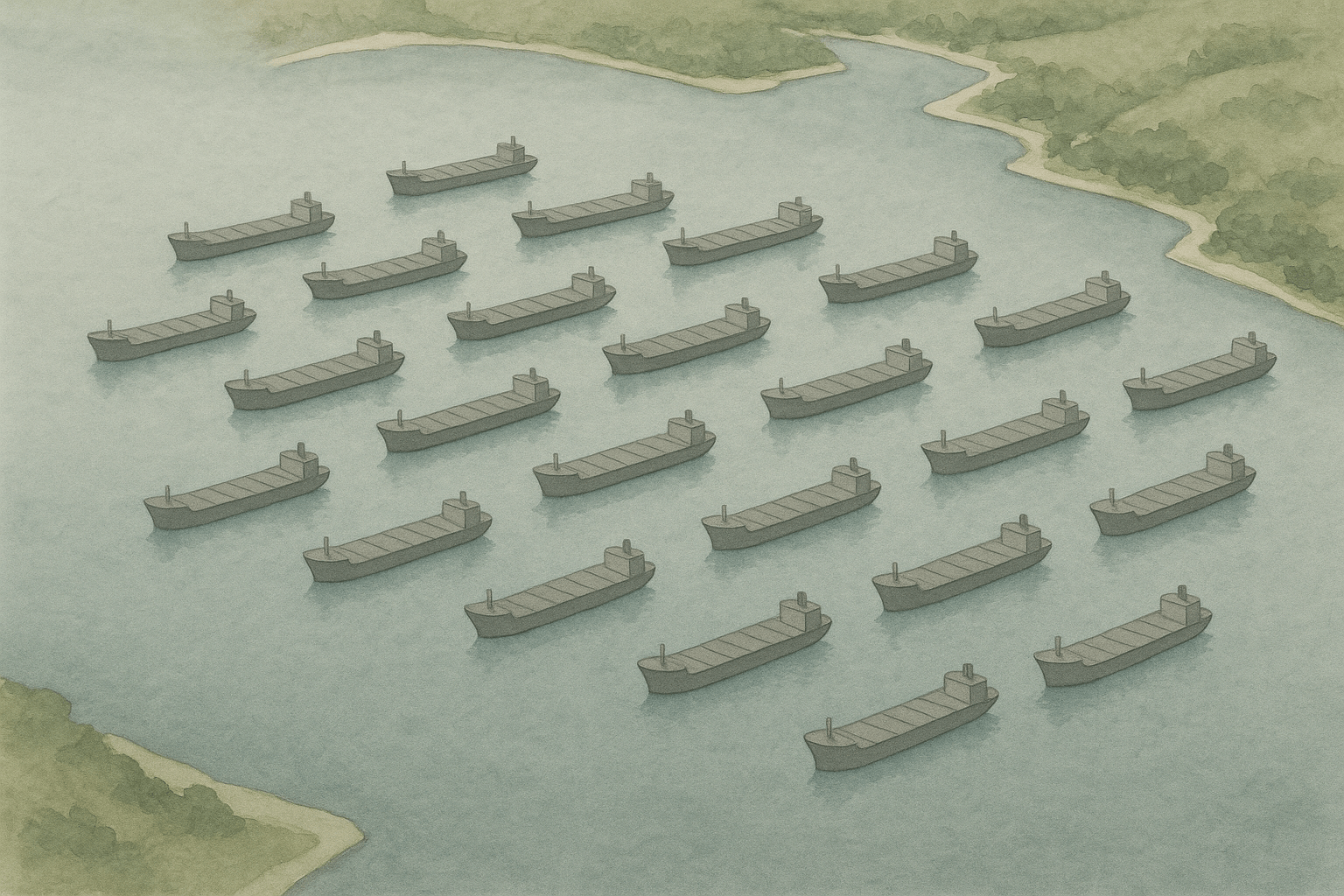

Off the coast of Singapore, nestled in the sheltered waters near Malaysia and Indonesia, lies a city of giants. It’s a silent, sprawling metropolis with no inhabitants, no traffic, and no commerce. This is one of the world’s most famous “ghost fleets”—a vast armada of idle cargo ships, colossal oil tankers, and bulk carriers, all anchored in a state of suspended animation. These are not shipwrecks or derelicts; they are perfectly functional vessels waiting for the invisible hand of the global economy to beckon them back to work.

These floating parking lots are the physical manifestation of global economic tides. When trade is booming, the world’s oceans are highways bustling with ships carrying everything from crude oil to consumer electronics. But when recessions hit, demand plummets, and shipping rates collapse, it becomes cheaper for companies to park their multi-million-dollar assets than to operate them at a loss. The result is these eerie, yet fascinating, ghost fleets.

The Economics of Idleness

The decision to take a ship out of service is a simple, yet brutal, calculation. The cost of running a massive vessel is immense: fuel (known as “bunker fuel”) can cost tens of thousands of dollars per day, and there are also crew salaries, insurance premiums, and port fees to consider. The profitability of the industry is often measured by indicators like the Baltic Dry Index, which tracks the cost of shipping raw materials.

When this index and other shipping rates fall below a vessel’s operating costs, owners are faced with a choice. They can either continue to sail and lose money on every voyage or enter a “lay-up.” A “hot lay-up” involves keeping a skeleton crew on board to maintain the machinery, allowing the ship to be reactivated within a week or two. A “cold lay-up” is more drastic: most systems are shut down, the crew is sent home, and the ship is essentially mothballed. This is cheaper long-term but can take months to reverse.

The 2008 financial crisis saw the birth of modern ghost fleets on a scale never seen before. As global trade seized up, the number of anchored ships exploded. Similar phenomena occurred during the oil glut of the mid-2010s, when a surplus of tankers were used as floating storage, and again briefly during the initial shock of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Perfect Parking Spot: A Geographical Recipe

You can’t just drop anchor anywhere. The locations of these ghost fleets are not random; they are chosen based on a specific recipe of physical and human geography that makes a location safe, accessible, and affordable.

Physical Geography: Shelter and Seafloor

The primary concern for an anchored vessel is safety from the elements. A ship at anchor is vulnerable to high winds and rough seas, which can cause the anchor to drag or, in the worst-case scenario, break free.

- Sheltered Waters: Ideal locations are deep, protected bays, fjords, lochs, or estuaries. These landforms act as natural breakwaters, shielding ships from the fury of the open ocean. Labuan, an island off the coast of Borneo in Malaysia, and the Firth of Forth in Scotland are classic examples.

- Sufficient Depth: The water must be deep enough to accommodate the massive draft of a supertanker (which can be over 20 meters), but not so deep that the anchor chain required becomes impractically long and heavy.

- Good Holding Ground: The nature of the seabed is critical. Soft mud or sand provides the best “holding ground”, allowing heavy anchors to dig in deep and grip securely. A rocky or gravelly bottom is dangerous, as anchors can fail to catch or may get permanently snagged.

Human Geography: Proximity and Price

Beyond the physical landscape, human factors are equally important. A lay-up location must be practical from a logistical and financial standpoint.

- Proximity to Shipping Lanes: Time is money. When the economy rebounds, a ship needs to get back into a major shipping lane as quickly as possible. This is why the waters around the Strait of Malacca, the world’s busiest shipping corridor, are the globe’s premier parking lot.

- Access to Infrastructure: Even in a “cold lay-up”, ships require maintenance and occasional checks. Locations near major port cities like Singapore, Piraeus in Greece, or Fujairah in the UAE offer access to skilled labor, spare parts suppliers, and launch boats to ferry crews and provisions.

- Favorable Regulations: The final piece of the puzzle is cost and bureaucracy. Some countries or port authorities offer lower anchorage fees and have streamlined processes for laying up vessels, making them economically attractive destinations for shipowners looking to cut costs.

A Global Tour of Ghost Fleets

While these fleets swell and shrink, a few key geographical locations have become synonymous with the phenomenon.

Singapore and the Strait of Malacca: This is the undisputed epicenter. The sheltered, deep waters off the coasts of Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia are perfectly situated along the main artery of trade between Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. On any given day, hundreds of vessels can be seen at anchor here, a silent testament to the region’s role as the nexus of global maritime logistics.

Elefsis Bay, Greece: Just west of Athens’ bustling port of Piraeus lies Elefsis Bay, a place that has served as a ship anchorage for millennia. While it’s often called a “ship graveyard” for older, decaying vessels, it is also a popular lay-up site. Its sheltered geography and Greece’s deep-rooted maritime industry make it an ideal spot for European shipowners to wait out economic storms.

Labuan, Malaysia: This island in East Malaysia became a prominent lay-up site, particularly for the offshore oil and gas industry. Its deep, protected bay and strategic location in Southeast Asia made it a go-to spot for oil rigs and support vessels during downturns in energy prices.

The Unseen Cost

Though they appear static, these ghost fleets are not without impact. A skeleton crew remains on board for hot lay-ups, leading a lonely existence maintaining the humming generators and watching for signs of trouble. Environmentally, the risks are real. The potential for fuel leaks, the scouring of the seabed by dragging anchors, and the constant low-level pollution from generators pose a threat to local marine ecosystems. These fleets are a stark reminder that even when the engines of global trade are idle, their presence leaves a footprint on the planet.

The next time you see a map of global shipping routes, remember the places that don’t appear—the quiet bays and sheltered coves where the world’s mighty ships go to rest. They are the ghost fleets, the world’s floating parking lots, and the most compelling geographical indicator of the health of our interconnected world.