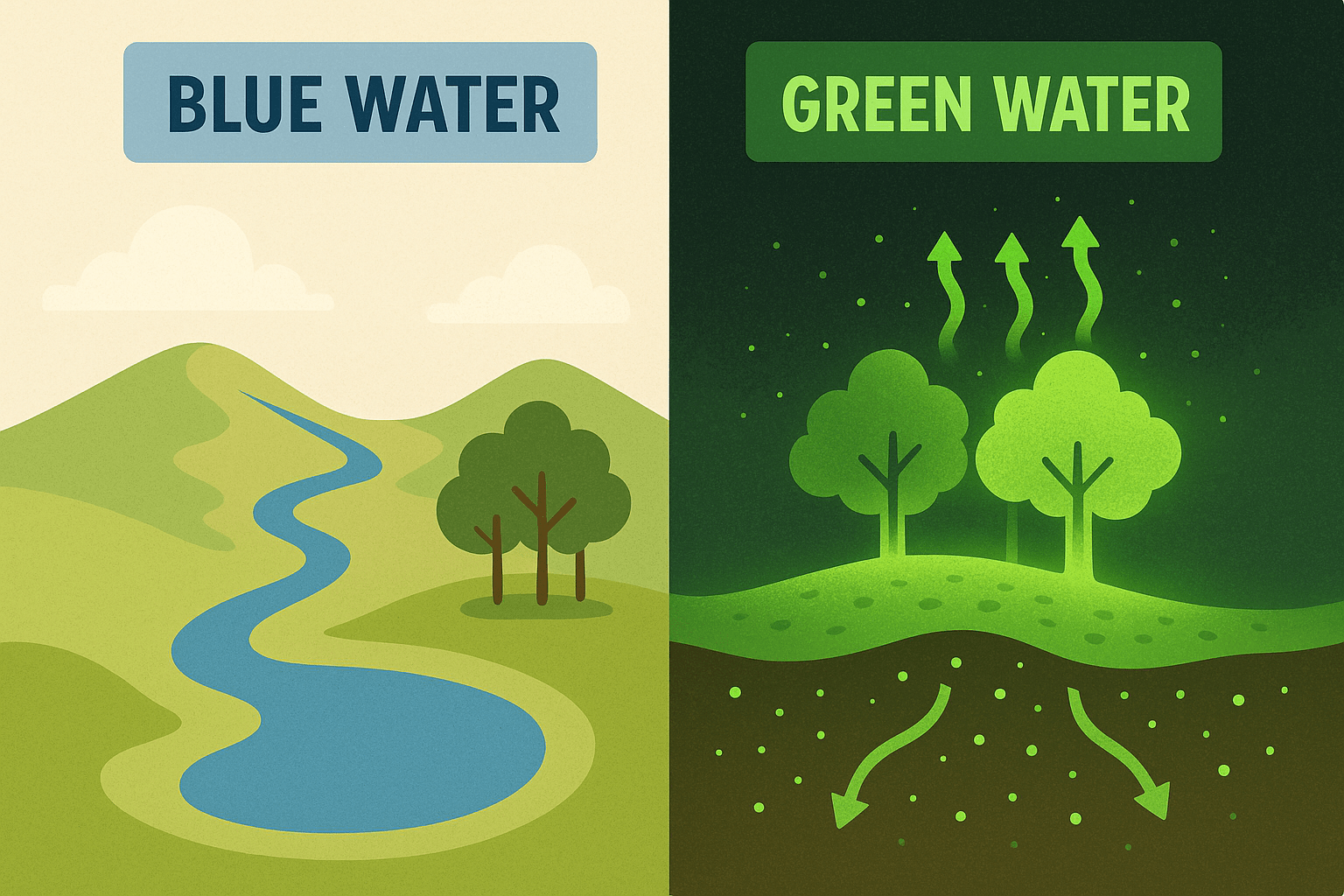

When you picture the Earth’s water, what comes to mind? For most of us, it’s the dramatic blues of our planet: the snaking path of the Amazon River, the vast expanse of Lake Superior, or the powerful rush of water over Niagara Falls. We see water as a resource to be dammed, diverted, and drawn from. This is what hydrologists call blue water, and it’s been the focus of human water management for millennia.

But what if I told you this visible, flowing water is only part of the story? What if the most important water for global food security and understanding droughts is largely invisible, held silently in the soil beneath our feet and within the very plants that sustain us? This is green water, and the failure to appreciate its role is one of the biggest blind spots in our approach to managing our planet’s most precious resource.

The Familiar Flow: Understanding Blue Water

Blue water is the liquid water in our rivers, lakes, wetlands, and, crucially, our groundwater aquifers. It is the runoff from rainfall and snowmelt that makes its way across the surface or seeps deep underground. Think of it as the planet’s plumbing system.

Its characteristics are defined by its movement and accessibility:

- Visible and Measurable: We can easily measure a river’s flow or a reservoir’s depth.

- Transportable: We can build canals, aqueducts, and pipelines to move it from where it is to where we want it.

- The Foundation of Cities: Blue water provides the drinking water for our cities, powers our industries, and irrigates a significant, though not the largest, portion of our farmland.

Geographically, our world has been shaped by the pursuit and control of blue water. Ancient Egypt was famously called “the gift of the Nile”, a civilization built entirely on the river’s predictable floods. In the modern era, the massive dams on the Colorado River in the United States or the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze in China are monuments to blue water engineering, re-shaping landscapes and enabling the growth of megacities in arid regions like Los Angeles and Phoenix.

Because it’s tangible, blue water dominates our policies, our economic models, and our headline news about water scarcity. But it only accounts for about 40% of the precipitation that falls on land.

The Unseen Majority: Unveiling Green Water

So, where does the other 60% go? It becomes green water.

Green water is the precipitation that is absorbed by the soil and vegetation, ultimately returning to the atmosphere through evaporation and transpiration (the release of water vapor from plants). It doesn’t flow into a river; it stays *in situ*, powering terrestrial ecosystems from the ground up. It is the moisture in the topsoil that germinates a seed, the water pulled up by the roots of a mighty oak, and the dew on a blade of grass.

Unlike blue water, green water is:

- Invisible and Diffuse: It’s a stock of moisture spread across a landscape, not a concentrated flow.

- Directly Productive: It is the water directly responsible for biomass growth—from forests and grasslands to the crops in our fields.

- The Engine of Rain-fed Life: It supports all non-irrigated agriculture, which accounts for over 80% of the world’s cultivated land and produces more than 60% of the world’s food.

Green Water: The Lifeblood of Agriculture

This is where the distinction becomes critical for human geography. While a massive irrigated farm in California’s Central Valley relies on blue water pumped from reservoirs or aquifers, the vast majority of the world’s farmers rely on something simpler: rain falling from the sky and staying in their soil. The cornfields of Iowa, the wheat belt of Ukraine, the millet farms in sub-Saharan Africa—these are all fundamentally green water systems.

Their success or failure is not determined by the level of a distant reservoir, but by the soil’s capacity to capture and hold rainfall. The livelihoods of billions of smallholder farmers depend directly on the management of this green water stock.

Drought Through a New Lens: The Green Water Deficit

Our traditional view of drought is a blue water one: pictures of cracked reservoir beds and catastrophically low river levels. But these are late-stage symptoms. Every major drought begins as a green water crisis.

A drought is fundamentally a soil moisture deficit. It starts when there is not enough green water available for plants to survive and grow. This is what scientists call an “agricultural drought.”

Think of the process:

- Rainfall decreases, or temperatures rise, increasing evaporation.

- There isn’t enough water to replenish the soil moisture; the green water stock dwindles.

- Plants wither and crops fail. This is the first and most immediate human impact, leading to food shortages.

- Only later, as the deficit continues, is there a significant reduction in runoff and percolation to recharge rivers and aquifers. The green water drought evolves into a “hydrological drought”—the blue water scarcity we see on the news.

Viewing drought through a green water lens helps us understand vulnerabilities far more clearly. The Horn of Africa, for instance, frequently suffers from devastating famines caused not by their major rivers running dry, but by the failure of seasonal rains to support grazing lands and small farms—a catastrophic failure of the green water system.

Shifting Our Focus: From Blue to Green Management

For centuries, our answer to water problems has been gray infrastructure for blue water: more dams, deeper wells, and longer canals. But if the majority of our food and ecosystems run on green water, a new approach is needed—one that focuses on the land itself.

Green water management involves strategies that increase the amount of rainfall the land can absorb and retain. These are often nature-based solutions that have cascading benefits for soil health and biodiversity:

- Conservation Agriculture: Practices like no-till farming and leaving crop residue on the field act like a mulch, reducing evaporation and allowing more water to infiltrate the soil.

- Cover Cropping: Planting crops like clover or vetch during the off-season protects the soil from erosion and improves its structure, turning it into a better sponge for water.

- Agroforestry: Integrating trees into farmland helps capture more water, reduce wind and water erosion, and improve the local micro-climate.

- Contour Plowing and Terracing: Farming along the contours of a slope, rather than up and down it, creates ridges that slow runoff and give water time to soak in.

A More Complete Picture of Our Water World

The distinction between blue and green water isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a fundamental shift in perspective. Blue water is the planet’s circulatory system, essential for life. But green water is the lifeblood held within the planet’s living tissues—its soils and its vegetation.

By focusing solely on the rivers and lakes, we are ignoring the largest and most productive part of the terrestrial water cycle. To build resilience to climate change, ensure global food security, and manage our landscapes sustainably, we must learn to see and value the invisible water all around us. The next time you walk across a lush park or look out over a field of wheat, remember what you’re really seeing: a vast, living reservoir of green water at work.