Imagine a substance so valuable it was dubbed “white gold.” A resource so strategic that nations launched colonial expeditions, passed unprecedented laws, and even went to war over it. This wasn’t gold, oil, or diamonds. It was guano—the accumulated, fossilized droppings of seabirds. In the 19th century, this potent fertilizer kickstarted a geopolitical frenzy, reshaping global agriculture, redrawing maps, and creating a unique empire built not on land or people, but on bird excrement.

The Geographical Goldmine: Why Bird Droppings Became a Global Commodity

Guano’s incredible value is a story of physical geography. For millennia, specific coastal regions, most notably the barren islands off the coast of Peru, provided the perfect conditions for its creation. The key ingredient is the Humboldt Current, a cold, deep, nutrient-rich ocean current that flows north along the western coast of South America. This cold water supports an astonishingly dense food web, starting with plankton that feed massive schools of anchovies.

These anchovies, in turn, provide an endless buffet for millions of seabirds, particularly the Guanay Cormorant, Peruvian Booby, and Peruvian Pelican. For centuries, these birds nested, lived, and defecated on the same remote, rocky islands. The final, crucial geographical element is the climate. The Peruvian coast is one of the most arid regions on Earth. The extreme lack of rainfall meant the bird droppings didn’t wash away; instead, they baked in the sun, slowly petrifying and concentrating their potent chemical compounds over thousands of years. On islands like the Chincha Islands, these deposits grew into literal mountains of guano, some towering over 150 feet high.

Before the 19th century, this was a local resource used by indigenous Andeans to fertilize their terraced farms. But when European scientists, like Alexander von Humboldt, brought samples back in the early 1800s, analysis revealed its power. Guano was packed with nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium—the essential macronutrients for plant growth. For the farms of Europe and North America, whose soils were becoming depleted after generations of intensive agriculture, guano was a miracle. It could triple or quadruple crop yields, feeding the booming populations of the Industrial Revolution.

Peru’s “Guano Age” and its Human Cost

Suddenly, the remote, desolate islands off Peru became the center of a global resource boom. From about 1840 to 1880, Peru entered its “Guano Age.” The government declared the guano a national asset and established a lucrative monopoly, selling consignments to European merchants, primarily the British. The profits were immense, flooding the national treasury.

This boom dramatically reshaped the human geography of Peru. The capital city, Lima, was transformed with grand new buildings, public lighting, and the first railways in South America, all financed by bird droppings. But this glittering age had a profoundly dark underbelly. The work of hacking away at the hardened, ammonia-choked mountains of guano was brutal and dangerous. Initially done by convicts and army deserters, the labor force soon became dominated by Chinese “coolies”—indentured laborers who were often tricked or coerced into contracts. They toiled in horrific, slave-like conditions, living in squalor on the very islands they were stripping bare. This era represents a tragic chapter of forced migration and exploitation, a direct human consequence of the global demand for this new resource.

American Ambition and the Guano Islands Act

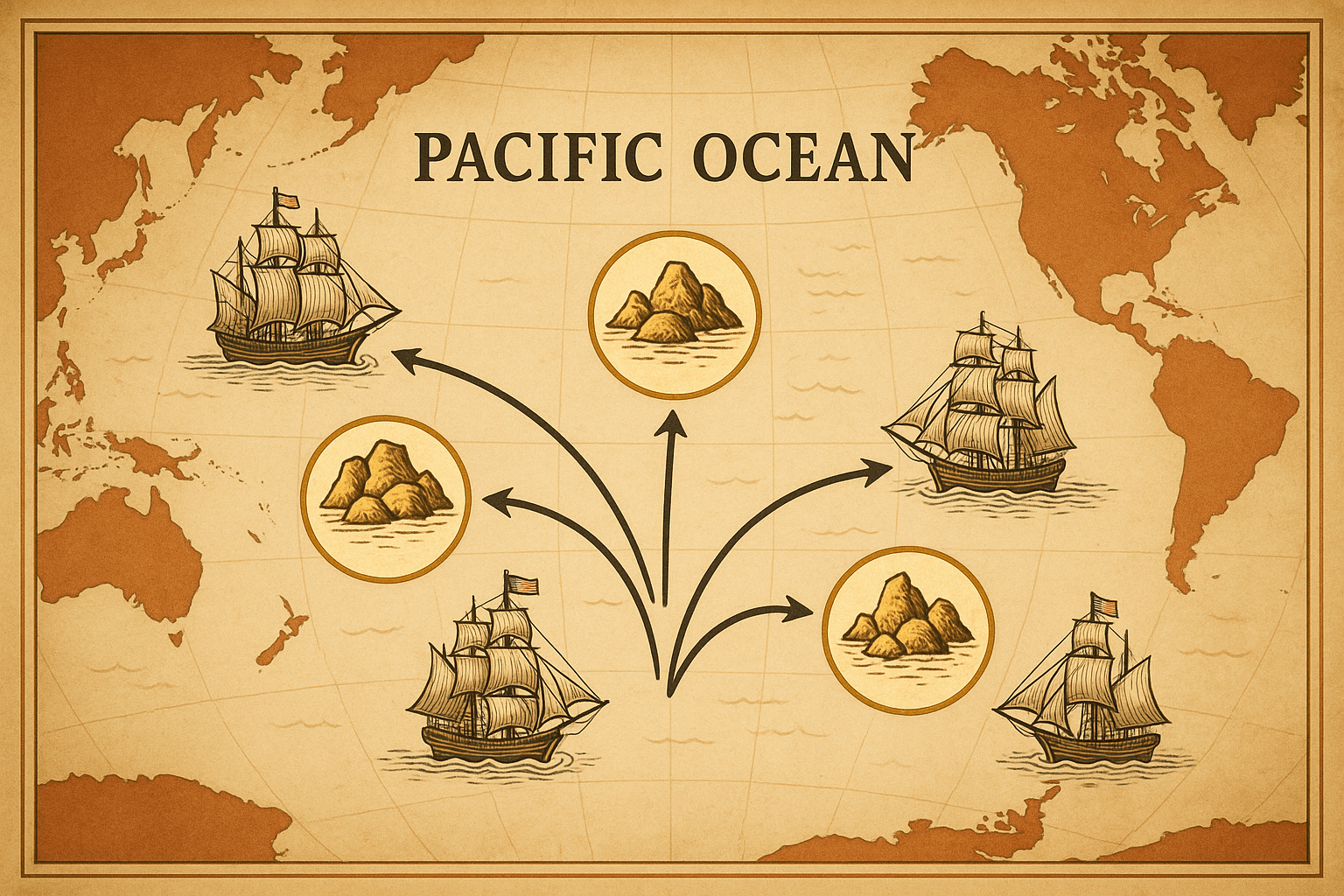

The United States, with its own expanding agricultural frontiers, was desperate to secure its own supply of guano and break the Peruvian monopoly. This led to a unique and audacious piece of legislation that defined American “Guano Imperialism”: the Guano Islands Act of 1856.

This remarkable law, which is still on the books, empowered any American citizen to claim any uninhabited, unclaimed island containing guano deposits, anywhere in the world, in the name of the United States. It was a formula for instant, low-cost colonialism. It wasn’t about settlement or civilizing missions; it was a naked resource grab. Under this act, the U.S. laid claim to nearly 100 islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. Many claims were short-lived, but several, like Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, and Navassa Island, remain U.S. territories to this day—a direct geopolitical legacy of the 19th-century fertilizer trade.

The War of the Pacific: A Conflict Fought Over Fertilizer

By the 1870s, the richest guano deposits on the Chincha islands were nearing exhaustion. The focus of the fertilizer world shifted slightly inland to the vast Atacama Desert, a bone-dry coastal plain where the borders of Chile, Bolivia, and Peru met. Here, instead of guano, were immense deposits of caliche, a mineral rich in sodium nitrate, another powerful fertilizer also known as “Chilean Saltpeter.”

The stage was set for the ultimate guano-era conflict: The War of the Pacific (1879-1884). The conflict erupted over a tax dispute between the Bolivian government and Chilean companies mining nitrate in the Bolivian coastal province of Antofagasta. When Bolivia moved to nationalize the Chilean-owned mines, Chile declared war. Peru, bound by a secret defensive alliance with Bolivia, was drawn into the conflict.

The war was a disaster for Peru and Bolivia. The powerful Chilean navy secured the sea lanes, and its army pushed north, occupying the nitrate-rich territories. The result was a permanent and dramatic redrawing of the South American map:

- Chile annexed the Peruvian province of Tarapacá and the Bolivian province of Litoral, gaining control of the world’s most valuable nitrate fields and extending its northern coastline significantly.

- Peru lost its southern territories and was plunged into financial ruin, ending its Guano Age.

- Bolivia lost its entire coastline, a catastrophic geopolitical blow that rendered it a landlocked country, a status that continues to define its economy and foreign policy to this day.

The End of an Empire

The Guano Empire, and the nitrate boom that followed, didn’t last forever. Its end came not from resource depletion alone, but from scientific innovation. In the early 20th century, German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed the Haber-Bosch process, a method for fixing atmospheric nitrogen to produce ammonia on an industrial scale. This discovery allowed for the creation of cheap, synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, making the perilous journey to remote Pacific islands obsolete.

Today, the guano islands are quiet once more, inhabited again mostly by birds. But they stand as a powerful monument to a bizarre and forgotten era of global history. The story of Guano Imperialism is a stark lesson in resource geography—a reminder of how a single, seemingly humble material can fuel economies, drive human migration, inspire imperial ambition, and ultimately, carve new lines on the world map.