Imagine a construction worker from a small village in Pakistan, now working in the glittering metropolis of Dubai. He needs to send his monthly earnings back to his family, but they live hours from the nearest bank, transfer fees are steep, and the formal process is slow. How does his money reach them quickly and reliably? The answer lies not in a bank, but in a centuries-old network built on a single, powerful commodity: trust. This is the world of Hawala, an informal value transfer system whose geography is as fascinating as its methodology.

At its core, Hawala is a method of moving value without physically moving money across borders. It operates through a web of brokers, known as hawaladars, who are connected by kinship, ethnicity, and a shared honour code. To understand its modern footprint, we must first trace its roots back through the annals of economic geography.

The Historical Geography of Trust: From the Silk Road to the Sea

The origins of Hawala are deeply intertwined with the physical and human geography of ancient commerce. Long before the advent of modern banking, merchants plying the Silk Road and Indian Ocean trade routes faced a significant geographical challenge: the danger of travel. Transporting gold, silver, and other valuables across treacherous deserts like the Gobi, formidable mountain ranges like the Hindu Kush, or pirate-infested waters was a risky proposition.

To mitigate this risk, traders developed informal systems based on honour. A merchant in Samarkand could deposit funds with a local broker and receive a token or a password. His counterpart in Aleppo could then present that token to a corresponding broker and receive the equivalent value. The debt between the two brokers would be settled later, perhaps through future transactions, a reverse transfer, or the trade of goods. This system, known in South Asia as hundi and in the Arab world as hawala (meaning “transfer” or “trust”), allowed commerce to flourish by dematerializing wealth and relying on the social fabric of the network.

This historical map of Hawala was etched along the major arteries of trade, connecting commercial hubs in the Middle East, South Asia, and the Horn of Africa. It was a geography dictated not by political borders, but by the flow of people, goods, and, most importantly, trust.

The Anatomy of a Modern Transaction: A Geographical Flow

Today, the principle remains remarkably unchanged, though the technology has evolved from handwritten chits to encrypted messages on WhatsApp. Let’s map a typical modern transaction to see how this geography works in practice:

- The Source Node: Aisha, a Somali nurse in Minneapolis, USA, wants to send $500 to her mother in Kismayo, Somalia. She visits a local Somali-owned market that doubles as a hawaladar. She hands over the $500 plus a small fee. In return, she receives a unique transaction code.

- The Network Communication: The Minneapolis hawaladar (Broker A) contacts his trusted counterpart in Kismayo (Broker B). He informs Broker B of the transaction amount and provides the code. The value, a $500 debt, is now logged in their shared, informal ledger. Crucially, no actual dollars have begun a journey to Somalia.

- The Destination Node: Aisha calls her mother and gives her the code. Her mother then visits Broker B in Kismayo.

- The Payout: After verifying her identity and the code, Broker B gives Aisha’s mother the equivalent of $500 in local currency (e.g., Somali shillings) from his own cash reserve.

In this geographical flow, the value has moved from a node in North America to a node in the Horn of Africa in a matter of hours, or even minutes. The physical money never crossed a border. The two brokers will settle their debt later, balancing it against other transactions flowing in the opposite direction or through other means. The system thrives because it is fast, cheap, and reaches places where formal financial geography ends—the “last mile” to remote villages or conflict zones where banks are non-existent.

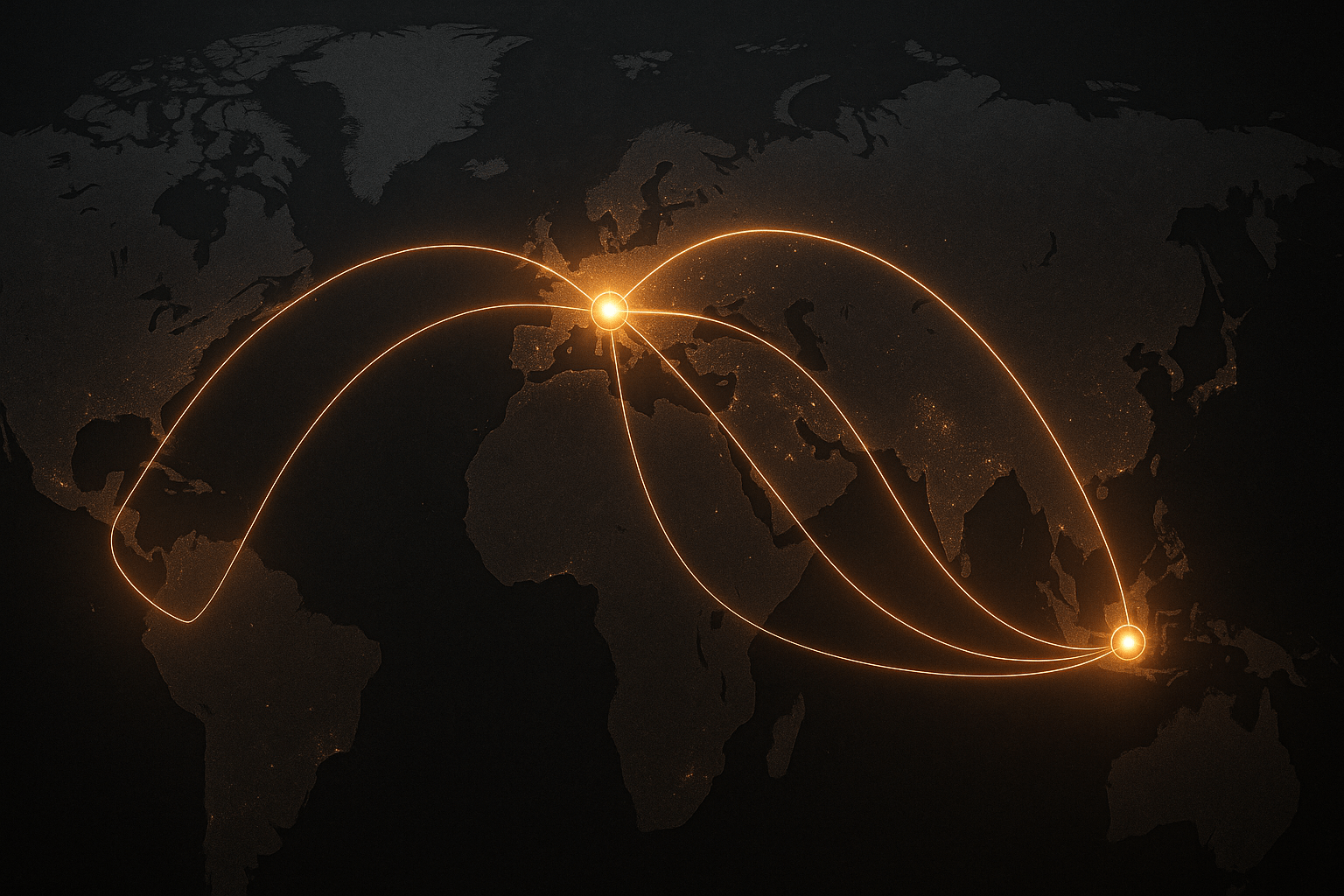

Mapping Modern Hawala Corridors

The contemporary map of Hawala is a direct reflection of modern human geography, primarily shaped by migration and the global economy. The network consists of major source regions, where migrant diasporas are concentrated, and destination regions, which are typically their home countries.

Major Source Hubs (Where Money Enters the System)

- The Persian Gulf: Cities like Dubai, Doha, and Riyadh are massive Hawala hubs. They host millions of migrant workers from South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa who use the system as a primary means of sending remittances home. Dubai, with its strategic location and massive expatriate population, is arguably the world’s Hawala epicentre.

- Western Europe: London, Paris, Berlin, and cities in Scandinavia with large immigrant communities from the Middle East, Horn of Africa, and South Asia are key source nodes.

- North America: Metropolitan areas like Toronto, New York, and Minneapolis, with significant diaspora populations, also serve as important points of entry for funds into the Hawala network.

Major Destination Corridors (Where Money is Paid Out)

- The South Asia Corridor: This is one of the largest and oldest corridors, connecting the Gulf and the West to Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and especially Afghanistan. For Afghanistan, a country ravaged by decades of conflict and with a shattered formal banking system, Hawala is not just an alternative but an essential economic lifeline.

- The Horn of Africa Corridor: Connecting diaspora communities in North America and Europe to Somalia, Ethiopia, and Eritrea. In Somalia, Hawala accounts for a staggering percentage of the GDP, funding everything from daily sustenance to small business startups.

- The Middle East & North Africa (MENA) Corridor: This network serves countries like Yemen, Syria, and Egypt, often facilitating remittances into regions destabilized by conflict or economic crisis, where sending money through formal channels is difficult or impossible.

–

The Shadow Geography of Hawala

It is impossible to discuss the geography of Hawala without acknowledging its dual-use nature. The very features that make it a lifeline for millions—anonymity, speed, and lack of a paper trail—also make it attractive for illicit activities. Its informal, borderless nature creates a “shadow geography” that can be exploited for money laundering and terrorist financing. After the 9/11 attacks, the system came under intense international scrutiny for its role in moving funds for extremist groups.

However, framing Hawala solely as a criminal enterprise is a profound mischaracterization. For the vast majority of its users, it is a tool of economic survival, a system that thrives in the vacuums left by the global financial system. It represents a geography of need, connecting families and sustaining economies in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions.

Ultimately, Hawala is more than just a financial mechanism; it is a map of human connection. It traces the paths of migration, the bonds of community, and the enduring power of trust in an uncertain world. It operates on a geography of its own making, one drawn not by banks or governments, but by the timeless human impulse to provide for one’s own, no matter the distance.