From a geographical perspective, cities are not just collections of buildings; they are dynamic arenas of social interaction, contested spaces where different groups vie for access and visibility. Hostile architecture, also known as defensive or exclusionary design, is a powerful tool in this contest. It uses the physical environment to enforce social norms and control behavior, often targeting the most vulnerable members of society.

What is Hostile Architecture? The Subtle Art of Exclusion

At its core, hostile architecture is the use of urban design elements to prevent or discourage specific activities in public spaces. The most common targets are behaviors like sleeping, loitering, skateboarding, and gathering in groups. While proponents frame it as a way to ensure safety, reduce crime, and maintain order, critics argue it’s an inhumane strategy that criminalizes poverty and homelessness without addressing their root causes.

The genius—and the insidiousness—of hostile architecture is its ability to blend in. It often masquerades as utilitarian street furniture, security measures, or even public art. A person with a home to go to might not think twice about a bench with dividers; for them, it’s just a place to sit for a few minutes. But for a person experiencing homelessness, that same bench is a clear message: you cannot rest here. You are not welcome. This selective discomfort is what makes the practice so effective and so ethically fraught.

A Global Catalogue of Hostile Design

The tactics of hostile architecture are remarkably consistent across the globe, a testament to how cities everywhere grapple with the same social issues. By learning to spot these features, you can begin to read the unspoken rules of the urban landscape.

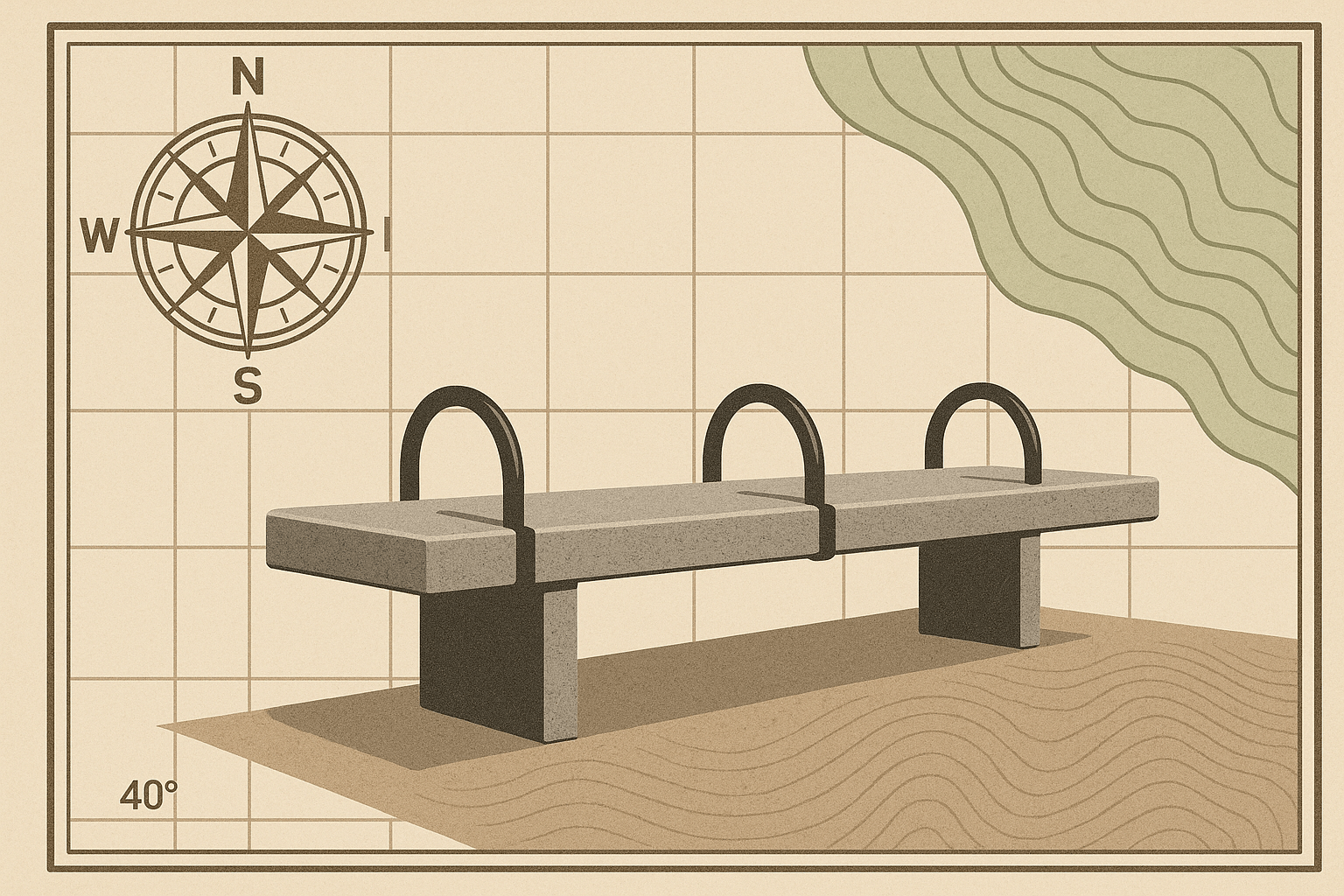

- The Divided Bench: Perhaps the most common example, these benches feature armrests or other dividers placed at intervals that make it impossible for a person to lie down. You can find them in bus shelters, parks, and train stations from New York City to Tokyo.

- Anti-Homeless Spikes and Studs: One of the most aggressive forms of hostile design, these are metal or concrete spikes embedded in flat surfaces—like doorways, ledges, and under bridges—to prevent sitting or sleeping. Infamous examples in London and Montreal have sparked public outrage, sometimes leading to their removal after protests.

- The Camden Bench: Hailed by some designers and reviled by others, the Camden Bench is a purpose-built piece of hostile street furniture originating in London, UK. Made of sculpted concrete, its surface is sloped and uneven, preventing sleep. It has no crevices where litter or drugs could be hidden, and it’s coated in a paint that repels graffiti. It is the epitome of designing for control.

- Leaning Bars: Why provide a bench when a simple bar to lean against will do? Found at many bus stops and transit platforms, these “leaners” offer minimal comfort and discourage long stays. They offer relief for a moment but prevent true rest, subtly discriminating against the elderly, pregnant individuals, or anyone needing more substantial support.

- Skate-Stoppers: Small metal brackets, often called “pig ears”, are bolted onto handrails, planters, and concrete ledges. Their sole purpose is to break up a smooth surface and prevent skateboarders from grinding on them, effectively sanitizing public space of youth culture.

- Inhospitable Slopes: A simple but effective trick is to build low walls, window sills, and other horizontal surfaces with a slight slope. It’s often too subtle to notice at a glance, but it makes sitting for any length of time uncomfortable or impossible.

The Geography of Exclusion: Who Controls Public Space?

This brings us to a fundamental question in human geography: Who has the right to the city? The term, popularized by geographer David Harvey, argues that all inhabitants should have a say in shaping and using the urban environment. Hostile architecture directly challenges this idea. It privatizes public space in spirit, if not in law, by allowing property owners, corporations, and municipal governments to dictate who belongs.

These decisions create a geography of exclusion. By making central, visible areas inhospitable, hostile architecture doesn’t solve homelessness, drug use, or youth disillusionment. It simply displaces these issues. People are pushed from the relative safety and resource access of city centers into marginal, less visible, and often more dangerous areas—industrial zones, riverbanks, or neglected alleyways. The problem isn’t solved; it’s just hidden from the view of those with the power and wealth to frequent the “cleaned-up” spaces.

This creates a fractured city. There’s the polished, comfortable city for tourists, shoppers, and office workers, and then there’s the shadow city for those who have been designed out. The built environment becomes a physical manifestation of social inequality.

The Controversy and the Pushback

The debate around hostile architecture is fierce. Proponents, often from Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) or local governments, argue that these measures are necessary for public safety and economic vitality. They claim that by preventing “anti-social behavior”, they are making public spaces more welcoming for the general population, protecting property, and encouraging commerce.

However, a growing movement of activists, artists, and citizens is pushing back. They argue that designing cities with hostility erodes compassion and our collective sense of community. Notable acts of resistance include:

- Creative Protests: The London-based group “Space, Not Spikes” famously covered a set of anti-homeless spikes with mattresses, pillows, and a small library, transforming a hostile space into a welcoming one and drawing international media attention.

- Public Documentation: Social media accounts and websites now catalogue examples of hostile design from around the world, raising public awareness and holding designers and city planners accountable.

- Advocacy for Inclusive Design: Architects and urban planners are increasingly calling for “inclusive design” principles that prioritize creating spaces that are accessible and comfortable for everyone, regardless of age, ability, or social standing.

Ultimately, the central critique is that hostile architecture is a cruel and lazy solution. It chooses to manage the symptoms of deep social problems like poverty, addiction, and a lack of mental health services with concrete and steel, rather than with compassion and resources.

Reading Your City’s Landscape

Hostile architecture is more than just uncomfortable furniture; it’s a statement about a city’s values. It’s a physical text that tells us who is valued and who is considered a problem to be moved along. So the next time you are out in your city, look around. Read the landscape. Ask yourself: Who is this space designed for? And, more importantly, who is it designed to exclude? The answers encoded in our streets reveal the true geography of our shared public life.