Our planet feels solid, permanent. But look closer at a map, zoom in with a satellite’s eye, or dig deep into the rock record, and you’ll find evidence of a violent, cosmic history. Earth is pockmarked with scars from celestial bombardments, colossal impacts that have shaped its geology, climate, and even the course of life itself. These are not mere craters; they are ancient, eroded, and often hidden geological features known as impact structures, or, more poetically, astroblemes—a Greek term meaning “star wounds.”

More Than Just a Hole in the Ground

When we think of an impact, we might picture the iconic, bowl-shaped Meteor Crater in Arizona. This is a “simple crater”, formed by a relatively small impactor. But the truly Earth-shattering events, those caused by asteroids or comets several kilometers wide, create “complex craters.” The initial impact vaporizes the projectile and a huge volume of terrestrial rock, while a powerful shockwave blasts a deep, transient cavity. Almost immediately, the ground rebounds, thrusting up a central peak or a ring of mountains within the crater floor.

Over millions of years, the forces of physical geography—wind, water, ice, and plate tectonics—go to work. They erode the crater rim, fill the depression with sediment, and contort the original structure until it is nearly unrecognizable from the ground. What remains is the astrobleme: a subtle, often vast, circular scar embedded in the planet’s crust, a ghost of a crater waiting to be discovered.

The Geologist’s Detective Kit: Finding Cosmic Scars

Identifying an astrobleme is a masterclass in geological detective work. Since many are not obvious circles on a map, scientists rely on a specific set of clues that can only be explained by the extreme pressures and temperatures of a hypervelocity impact.

- Geographical Morphology: The first hint often comes from above. Satellite imagery and topographic maps can reveal vast, circular patterns that defy conventional geology. A river might make an unnaturally sharp turn, or a chain of lakes might form a perfect arc. These large-scale geographical phenomena are often the first breadcrumb on the trail.

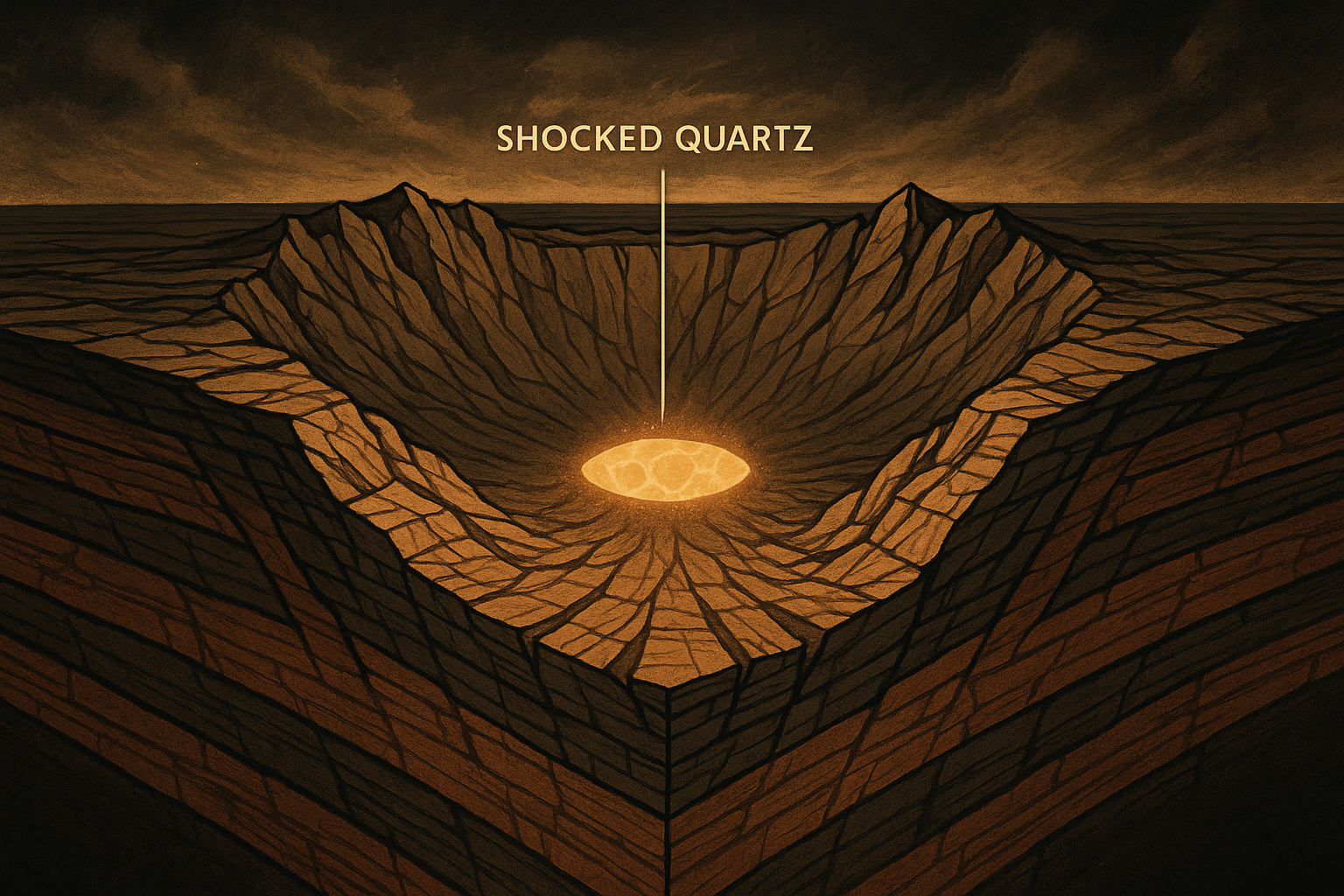

- Shock Metamorphism: This is the smoking gun. The intense shockwave from an impact creates changes in rocks and minerals that are found nowhere else on Earth. Geologists search for shatter cones, distinctive cone-shaped fractures in rocks that point back towards the impact center. They also look for shocked quartz under the microscope. This common mineral develops unique, microscopic parallel lines (called planar deformation features) when subjected to the kind of immense pressure that only an impact can produce.

- Geochemical Evidence: Asteroids and comets have a different chemical composition than Earth’s crust. An impact event vaporizes the impactor, scattering its components far and wide. This can leave a thin layer of elements that are rare on Earth’s surface, like iridium. The famous “iridium anomaly” found in a clay layer around the world marks the catastrophic impact that occurred 66 million years ago.

A Global Tour of Earth’s Astro-Scars

Impact structures are found on every continent, each telling a unique story of geography and time. They are not just geological oddities; they are features that have been integrated into the physical and human landscape.

Vredefort Dome, South Africa

Located in the Free State province of South Africa, the Vredefort structure is the world’s largest and oldest confirmed astrobleme, originally estimated to be 300 km (186 miles) across. The impact occurred over 2 billion years ago, and subsequent erosion has stripped away the original crater, leaving only the deeply eroded “roots.” The central peak, known as the Vredefort Dome, is a landscape of rolling hills sliced through by the Vaal River. Today, this UNESCO World Heritage Site is home to the town of Vredefort and is a hub for tourism and geological research, a place where human geography nestles within a scar of Precambrian age.

Chicxulub Crater, Mexico

Perhaps the most famous impact structure, Chicxulub is the wound left by the asteroid that led to the demise of the dinosaurs. Buried beneath the Yucatán Peninsula and the Gulf of Mexico, this 180 km (110 mile) wide crater is completely invisible on the surface. It was discovered through gravity and magnetic surveys in the late 20th century. A stunning piece of physical geography provides a clue to its location: a near-perfect arc of cenotes (water-filled sinkholes) on the peninsula marks the weakened, fractured limestone along the crater’s buried rim, a unique hydrogeological expression of a cosmic catastrophe.

Manicouagan Reservoir, Canada

One of the most visually spectacular impact structures from space is Manicouagan in Québec. This 214-million-year-old astrobleme features a prominent, 70 km (43 mile) wide inner ring that is now filled with water, forming the Manicouagan Reservoir. Often called the “Eye of Quebec”, this annular lake is a testament to how human engineering can adapt and utilize these ancient features. The structure’s uplifted central peak, Mount Babel, now forms an island in the middle of the hydroelectric reservoir, a stark reminder of the violent rebound that followed the impact.

Nördlinger Ries, Germany

For a perfect fusion of human and impact geography, look no further than the Ries crater in Bavaria. This well-preserved, 24 km (15 mile) wide crater formed about 15 million years ago. For centuries, residents believed the circular depression was a volcanic caldera. The historic town of Nördlingen is built entirely within the crater floor, its circular town wall tracing the unique geography. In a remarkable twist, the town’s church, St. Georg’s, is constructed from suevite, a type of rock composed of cemented fragments (a breccia) that was formed during the impact itself. The residents of Nördlingen literally live inside, and have built their city from, the remnants of a cosmic collision.

Living with the Scars

Earth’s astroblemes are more than just historical footnotes. They actively shape our world. Some of the world’s most significant ore deposits are associated with impacts; the Sudbury Basin in Ontario, Canada, is a deeply eroded astrobleme that is a primary source of the world’s nickel and copper. Apollo astronauts even trained in the Ries and Sudbury craters to learn how to identify impact-related rocks on the Moon.

From the cenotes of Mexico to the mineral wealth of Canada and the medieval walls of Nördlingen, these scars are woven into the fabric of our planet. They are a powerful, humbling reminder that our world is part of a larger, dynamic cosmos. The ground beneath our feet is a history book, and the astroblemes are its most dramatic chapters, telling stories of destruction, resilience, and the enduring connection between Earth and the stars.