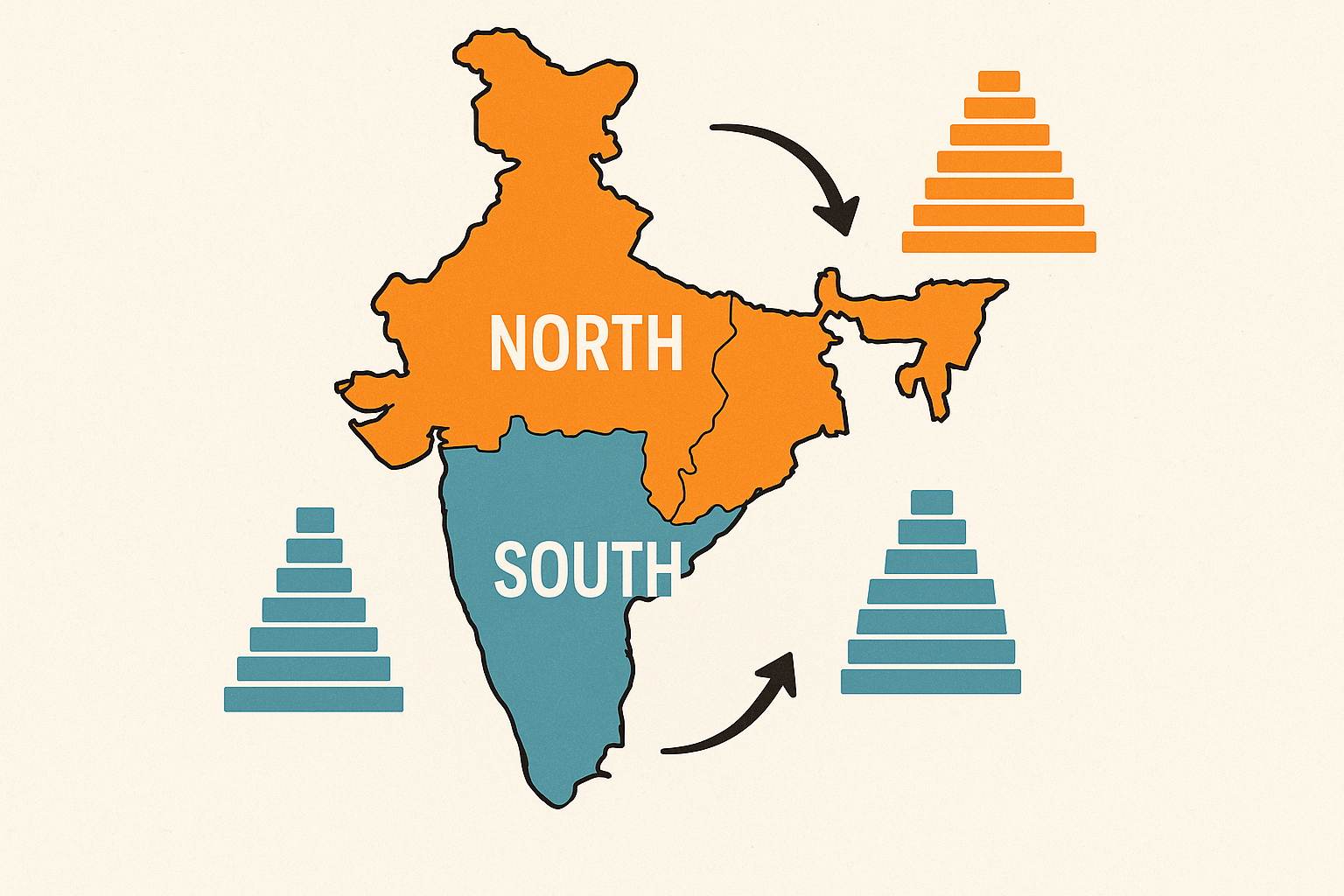

Travel across India, and you’ll experience a dizzying array of cultures, languages, and landscapes. But beneath this vibrant diversity lies a more profound, almost invisible split. It’s a demographic fault line that cleaves the subcontinent into two distinct entities, creating what is often called “two Indias.” To the south of the Vindhya mountain range, you find a region with demographics resembling aging European nations. To the north, you find a massive, burgeoning population with a youth bulge that mirrors parts of sub-Saharan Africa. This is not just a statistical curiosity; it’s a geographical reality with seismic consequences for India’s political and economic future.

A Tale of Two Indias: Mapping the Demographic Fault Line

The simplest way to visualize this divide is through a single, powerful statistic: the Total Fertility Rate (TFR), which is the average number of children a woman is expected to have in her lifetime. The replacement rate—the level at which a population replaces itself from one generation to the next—is 2.1. Any number below this indicates a shrinking or stabilizing population.

Let’s draw a rough line across central India, from Gujarat in the west to West Bengal in the east. Broadly speaking, the states south of this line tell one story, while the states north of it tell another.

The Southern Story: An Aging, Educated Populace

States like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Karnataka have undergone a dramatic demographic transition. Their TFRs have plummeted far below the replacement level. For instance, according to the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), Tamil Nadu’s TFR is 1.8, and Kerala’s is 1.8. This is comparable to countries like France and Australia.

What does this mean on the ground?

- Aging Population: With fewer children being born and life expectancy rising, the average age in the South is increasing rapidly. They are grappling with issues of elderly care and a shrinking workforce, much like Japan or Italy.

- Higher Human Development: This demographic shift is closely linked to higher female literacy, better healthcare infrastructure, and greater female participation in the workforce. Kerala, for example, consistently tops India’s Human Development Index.

- Economic Powerhouses: These states are drivers of India’s modern economy, excelling in manufacturing, technology, and services. Cities like Bengaluru and Hyderabad are global tech hubs.

The Northern Narrative: The Power of the Youth Bulge

In stark contrast, the populous states of the Hindi-speaking heartland—Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan—present a completely different picture. Here, the TFRs remain significantly higher. Bihar’s TFR is a staggering 3.0, while Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state with over 240 million people, has a TFR of 2.4.

This creates a massive “youth bulge”, where a large proportion of the population is under the age of 25. This presents both a monumental opportunity and a formidable challenge:

- The Demographic Dividend: This enormous young population could, in theory, become a powerful engine for economic growth if they are provided with quality education, skills, and jobs.

- Strain on Resources: For now, it places immense pressure on a state’s resources. Providing education, healthcare, and employment for tens of millions of young people every year is a gargantuan task.

- Development Lag: These states generally lag in socio-economic indicators, including female literacy and public health, which are both causes and effects of the high fertility rates.

Why the Divergence? The Human Geography Behind the Numbers

This North-South chasm didn’t appear overnight. It’s the result of decades of differing paths in policy, social reform, and economic development.

Southern states were pioneers in implementing public health and family planning programs with greater administrative efficiency. Critically, these policies were coupled with a strong emphasis on female education and empowerment. When women are educated and have agency over their lives, they tend to have fewer children and invest more in each child’s future. Social reform movements in the South also played a crucial role in challenging patriarchal norms earlier and more effectively than in the North.

Conversely, in large parts of the North, these programs were implemented less effectively, and deeply entrenched patriarchal structures meant that female education and autonomy lagged. The economy remained largely agrarian, a setting where larger families were traditionally seen as an economic asset.

The Coming Quake: Political and Economic Futures on the Line

This demographic divergence is now set to collide with India’s political structure, creating a scenario fraught with tension.

The Delimitation Time Bomb

The most explosive issue is parliamentary representation. The number of seats each state gets in India’s lower house of Parliament (the Lok Sabha) is currently frozen based on the 1971 census data. This was done to encourage states to pursue family planning without the fear of losing political power.

However, this freeze is set to expire after 2026. A new delimitation exercise, which redraws constituency boundaries based on the current population, is on the horizon. If seats are reallocated based on today’s population figures, the political map of India will be radically redrawn.

The populous northern states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar would gain a significant number of seats. The southern states, which have successfully controlled their populations and powered the nation’s economy, would lose seats and, consequently, their political voice on the national stage. This has created a deep-seated fear in the South that their economic contributions, which heavily subsidize the poorer northern states through tax distribution, will be further exploited by a federal government dominated by northern interests.

Migration: The Great Connector and a Source of Strain

Economics and demographics are already interacting through migration. Millions of young men and women from the North are migrating to the South to find work in factories, construction sites, and the service industry, filling the labor gap left by the South’s aging population. This flow is a lifeline for both regions: it provides remittances for northern families and fuels southern industries.

But it also puts a severe strain on the urban infrastructure of southern cities like Chennai, Bengaluru, and Kochi, leading to challenges in housing, water, and sanitation. It can also, at times, create social friction between local populations and migrant communities.

Navigating the Divide: A Unified Path for a Divided Demography?

India is truly a nation of contrasts, but this North-South demographic divide is arguably the most consequential of them all. It shapes everything from economic policy and resource allocation to the very balance of power in the world’s largest democracy.

The challenge for India is immense: how to harness the potential of the North’s demographic dividend while addressing the political and economic anxieties of the South. Bridging this gap will require a delicate political consensus, targeted investment in the North’s human capital, and a new federal bargain that respects the contributions of all its states. How India manages this internal, geographically-defined divergence will determine its trajectory for the 21st century.