Imagine an industrial park. You probably picture smokestacks, sprawling factories, and waste streams flowing out. Now, imagine that same park as a living, breathing ecosystem, where the waste of one company becomes a vital resource for another. This isn’t a futuristic fantasy; it’s the reality in Kalundborg, a modest port town on the Danish island of Zealand. For over 50 years, this community has been the world’s leading, and perhaps most famous, example of Industrial Symbiosis—a geographical phenomenon that turns industrial waste into industrial wealth.

Pinpointing Kalundborg: A Port Town’s Transformation

To understand Kalundborg’s success, we must first look at a map. Located on the west coast of Zealand, Denmark’s largest island, Kalundborg sits strategically on a deep-water inlet called the Kalundborg Fjord, which opens into the Great Belt strait. This physical geography has long defined its human geography; it’s a natural hub for shipping and heavy industry. And it’s this close proximity of large industrial players—a power station, a refinery, and pharmaceutical giants—that laid the groundwork for one of the most remarkable stories in sustainable development.

What started in the 1960s not as a grand environmental plan, but as a series of practical, economically-driven deals between neighbouring companies, has evolved into a complex web of exchanges. This network has transformed the town’s industrial landscape from a collection of isolated entities into a single, integrated system that mimics the efficiency of nature.

What is Industrial Symbiosis? Nature’s Blueprint for Industry

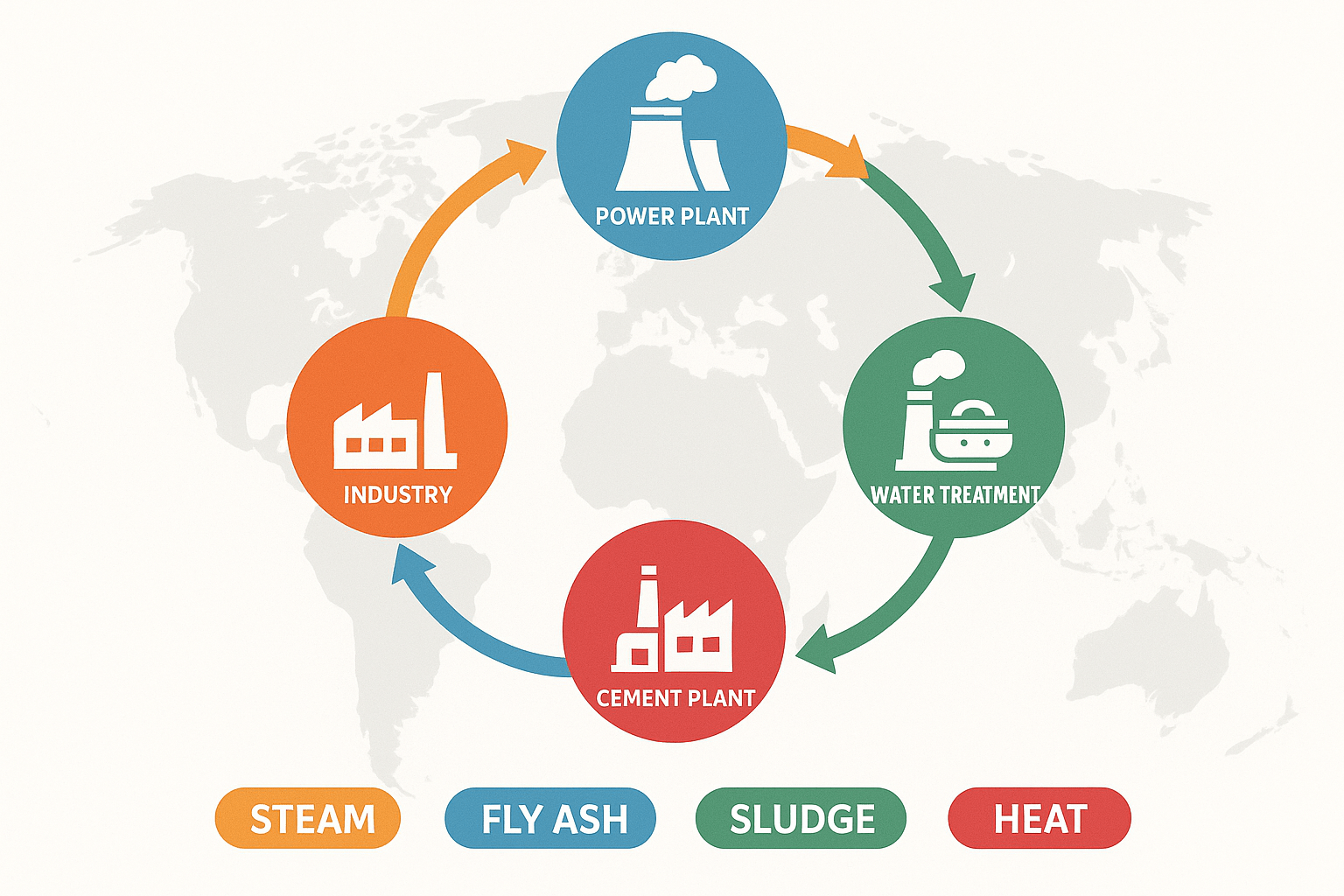

In a natural ecosystem, there is no such thing as “waste.” The fallen leaves of a tree decompose to nourish the soil, and the waste of one animal is a food source for another. Industrial Symbiosis applies this same principle to the industrial world. It’s a collaborative approach where physically-close industries create a closed-loop system by trading and sharing resources, by-products, water, and energy.

Instead of companies each sourcing their own raw materials and paying to dispose of their own waste, they create a local, circular economy. One company’s waste steam becomes another’s heating source. A chemical by-product from one process becomes a raw material for another. This isn’t just about recycling; it’s a holistic redesign of industrial processes on a geographic, community-wide scale.

The Kalundborg Network: A Symphony of Exchange

The heart of Kalundborg’s symbiosis is the intricate network of “pipes”—both literal and figurative—that connect the town’s key industrial players. The main partners include:

- Ørsted: The Asnæs Power Station, one of Denmark’s largest power plants.

- Kalundborg Refinery: Denmark’s largest oil refinery.

- Novo Nordisk: A global pharmaceutical company, famous for insulin production.

- Novozymes: The world’s largest producer of industrial enzymes.

- Gyproc: A manufacturer of gypsum wallboards.

Geographic Process Diagram: The Kalundborg Flow

Visualizing the network helps to grasp its genius. Imagine a map of the Kalundborg industrial area, with arrows crisscrossing between the facilities:

- ➡️ From Ørsted (Power Plant):

- Steam: High-pressure steam is piped to the Kalundborg Refinery for its processes. Lower-pressure steam goes to Novo Nordisk and Novozymes for sterilization and heating, and also heats about 5,000 local homes.

- Fly Ash & Clinker: A by-product of coal combustion is sold to cement manufacturers.

- Gypsum: Desulfurization of flue gas creates high-quality gypsum, which is piped as a slurry to Gyproc to make plasterboard.

- ➡️ From Kalundborg Refinery:

- Flare Gas: Excess gas that would otherwise be burned off is sent back to the Ørsted power plant as fuel.

- Cooling Water: Seawater used for cooling is sent to Ørsted for use as boiler feedwater, reducing thermal pollution and water intake.

- Sulfur: Sulfur recovered from refining oil is sold as a raw material for sulfuric acid production.

- ➡️ From Novo Nordisk & Novozymes:

- Biomass Sludge: Nutrient-rich sludge from fermentation processes is treated and used by local farmers as a natural fertilizer, returning nutrients to the soil.

- ➡️ Water & Heat Exchange:

- Surface water from Lake Tissø is supplied to the industries, reducing the strain on groundwater. The water is used in a cascading system, cleaned and reused multiple times before final discharge.

The Human Geography of Cooperation

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the Kalundborg Symbiosis is that it wasn’t designed by a central government planner or an environmental committee. It grew organically, from the ground up. The first deal was struck in 1961 to supply water from Lake Tissø to the refinery. A decade later, the gypsum-to-Gyproc pipeline was built. Each new connection was a bilateral agreement, a handshake between two companies that made simple economic sense.

This reveals a crucial lesson in human geography: trust and communication are as vital as pipes and infrastructure. The plant managers in Kalundborg knew each other. They socialized, built relationships, and found practical solutions to mutual problems. They realized that selling their “waste” was cheaper than disposing of it, and buying a neighbour’s by-product was more affordable than sourcing virgin materials. This pragmatic, economically-driven cooperation created profound environmental benefits as a welcome side effect.

The Ripple Effect: Environmental and Economic Wins

The results of this five-decade-long collaboration are staggering. The Kalundborg Symbiosis website reports impressive annual savings, including:

- Water: Over 3.6 million cubic meters of surface and groundwater saved.

- Energy: Substantial fuel savings by sharing steam and using excess gas.

- Materials: Over 150,000 tons of gypsum avoided landfill, instead creating a valuable product.

- CO2 Emissions: A reduction of over 635,000 tons per year.

These numbers represent more than just corporate savings; they translate to significant environmental protection. By reducing the need for raw materials, the symbiosis lessens the impact of mining and extraction elsewhere in the world. By conserving water and reducing emissions, it strengthens the resilience of the local ecosystem. The economic benefits reinforce the environmental ones, creating a powerful business case for sustainability that is hard to ignore.

Kalundborg’s Legacy: A Model for the World?

Kalundborg stands as a powerful testament to the potential of the circular economy. It demonstrates that industry and ecology do not have to be at odds. But can this model be replicated elsewhere?

The conditions in Kalundborg were unique: a diverse mix of industries in close geographical proximity, a culture of trust, and a long-term perspective. However, the principles are universal. Urban planners and industrial developers worldwide now look to Kalundborg for inspiration, designing new “eco-industrial parks” with symbiosis in mind from day one.

The quiet Danish port town has provided a living blueprint, proving that by thinking geographically and connecting locally, our industrial world can learn to function more like the natural one—efficient, resilient, and waste-free.