Imagine the sun beating down on a vast, ochre-colored expanse. The air shimmers with heat, and the silence of the desert is broken only by the whisper of a hot, dry wind. This is the heart of the Iranian Plateau, a region where summer temperatures can soar past 40°C (104°F). For centuries, survival—let alone comfort—in this landscape has demanded extraordinary ingenuity. Long before the advent of electricity and Freon, ancient Persians engineered their own climate, not by fighting the environment, but by working with it. Their solution stands tall against the sky in cities like Yazd: the elegant, mysterious, and brilliantly effective Bādgir, or windcatcher.

These towers are not mere decoration. They are the silent, beating heart of a passive cooling system that is a masterclass in applied geography and physics, shaping not just individual buildings but the very fabric of urban life.

The Unforgiving Canvas: Geography of the Iranian Plateau

To understand the windcatcher, one must first understand the land that birthed it. Central Iran is a high-altitude plateau, dominated by two vast salt deserts, the Dasht-e Kavir and the Dasht-e Lut. This is a classic arid environment: scorching hot days, surprisingly cool nights, and very little precipitation. The physical geography presented a stark challenge to human settlement. How do you build a sustainable city where the air itself feels like a furnace?

The answer lay in observing and harnessing the region’s geographical phenomena. The inhabitants noticed two key things: the existence of prevailing winds, even if they were hot, and the significant temperature difference between the sun-baked surface and the cool earth just a few meters below ground.

Anatomy of a Breeze: The Physics of the Bādgir

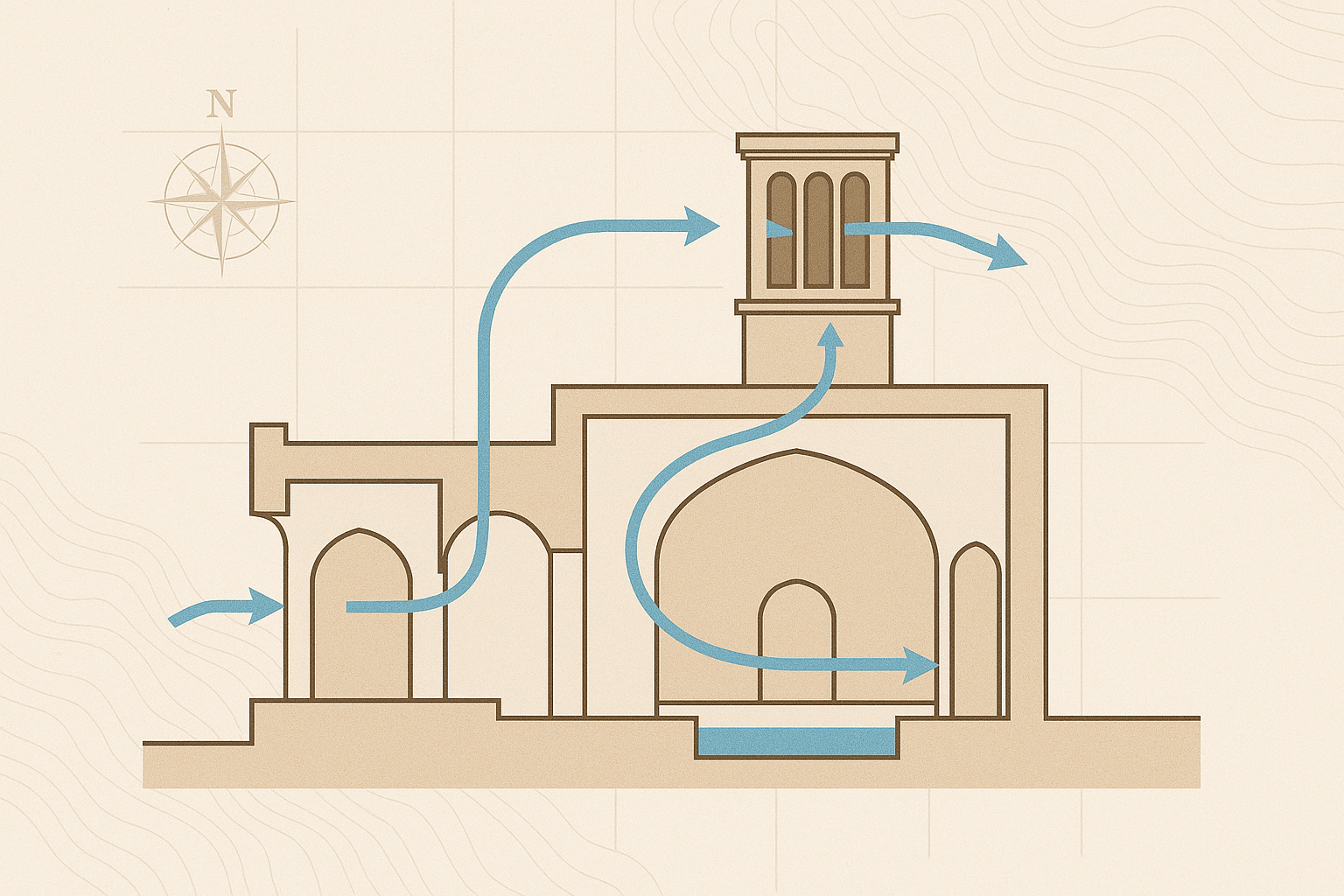

At its core, a windcatcher is a tower that rises from a building’s roof, featuring vertical shafts with openings at the top. While they may look similar from afar, their internal structure and design vary to suit local wind conditions. They operate on two simple yet powerful principles.

Principle 1: Catching the Wind (Wind-Driven Ventilation)

This is the most intuitive function. The openings at the top of the tower face the prevailing winds. The Bādgir “catches” this moving air and funnels it down a shaft into the living spaces below. This creates a refreshing draft, providing convective cooling—the pleasant sensation of air moving across the skin. Just as importantly, this downward pressure forces the hot, stagnant air already inside the building to be pushed out through other windows or openings, creating a continuous cycle of fresh air.

Principle 2: The Solar Chimney (Buoyancy-Driven Ventilation)

But what about on still, windless days? This is where the true genius lies. The tower itself acts as a solar chimney. As the sun beats down on the Bādgir, it heats the column of air trapped inside one of its shafts (often the one facing away from the sun). Hot air is less dense and begins to rise. This upward movement creates a pressure difference, effectively sucking cooler air from below up into the living space. This air is often drawn from a cool basement (sardāb) or a shaded courtyard, creating a gentle, persistent breeze even when there is no wind to “catch.”

The Secret Ingredient: The Qanat Connection

The system gets even more sophisticated. The Bādgir was often part of an integrated environmental design that included another marvel of Persian engineering: the Qanat. A qanat is a gently sloping underground channel that taps into an alluvial aquifer and transports water across long distances for irrigation and domestic use, all through the power of gravity.

Many traditional homes and gardens were built directly over these subterranean streams. When a windcatcher channeled air down into the building, it was often passed over the cool, flowing water of the qanat in the basement. This process achieved two things:

- Evaporative Cooling: As the hot, dry air from the Bādgir passes over the water, the water evaporates, a process that absorbs a significant amount of heat from the air. The result is air that is not just moving, but actively chilled.

- Humidification: The process also adds a small amount of moisture to the bone-dry desert air, making it more comfortable for inhabitants.

This combination of the Bādgir and the qanat created a truly passive, zero-energy air conditioning system, making rooms delightfully cool even on the most oppressive days.

Yazd: The City of Windcatchers

Nowhere is this architectural heritage more visible than in the city of Yazd. A UNESCO World Heritage site, Yazd’s skyline is a forest of Bādgirs. Walking through its labyrinthine network of narrow, shaded alleyways, you are constantly looking up at these earthen towers. The entire urban design of the old city is a testament to climate-sensitive architecture. The buildings, constructed from adobe and mud-brick, have thick walls that provide excellent insulation. Courtyards with pools of water create microclimates, and the Bādgirs rise above them to pull in the breeze.

A shining example is the windcatcher at Dowlat Abad Garden in Yazd. Standing at over 33 meters, it is one of the tallest in the world. It presides over a beautiful pavilion, pulling air down and across a marble pool to cool the summer residence of a long-ago ruler. It’s a living, breathing demonstration of the system’s elegance and power.

Ancient Wisdom for a Modern Climate

The Bādgir is more than an architectural curiosity; it is a profound lesson in sustainability. It represents a way of life deeply connected to its geographical context—a model of human geography where culture, society, and technology co-evolved in response to the physical environment.

In an era grappling with climate change and the high energy costs of modern air conditioning, the principles of the Bādgir are more relevant than ever. Architects and engineers are studying these ancient structures for inspiration in designing modern “passive houses” and low-energy ventilation systems. The Bādgir reminds us that the most sophisticated solutions are often born from a simple, intelligent collaboration with nature. It stands as a timeless monument to the idea that with enough ingenuity, humanity can find comfort even in the most extreme corners of our world.