Picture a world where elephants are the size of ponies and insects can outweigh a sparrow. This isn’t a scene from a fantasy novel, but a real-world evolutionary phenomenon driven by one of the most powerful forces on our planet: geography. Scattered across the globe, islands have acted as isolated natural laboratories, pushing evolution in strange and wonderful directions. The result is a fascinating pattern known as the “island rule”, where, in the absence of mainland pressures, large animals tend to shrink, and small animals tend to grow to epic proportions.

This process, a cornerstone of island biogeography, reveals the profound and sometimes bizarre ways that life adapts to the unique spatial constraints of an isolated environment. It’s a story of resources, predators, and the relentless drive for survival on a patch of land surrounded by water.

Why Islands are Nature’s Evolutionary Laboratories

To understand why a species might dramatically change its size, we first need to appreciate what makes an island geographically unique. Unlike vast continents with interconnected ecosystems, islands are, by their very nature, defined by two key characteristics: isolation and limitation.

- Isolation: A significant body of water acts as a formidable barrier, limiting or completely preventing gene flow between island populations and their mainland relatives. This genetic seclusion means the island population is on its own evolutionary trajectory.

- Limitation: Islands have finite space and finite resources. There’s only so much food, water, and territory to go around. Furthermore, they often have a simplified ecosystem, meaning fewer types of predators, competitors, and prey than on the mainland.

This unique combination of isolation and limitation creates intense selective pressures. Traits that might be advantageous on a continent could become a liability on an island, and vice versa. Over thousands of generations, these pressures sculpt species into new forms, perfectly adapted to their miniature world.

The Case of the Shrinking Giants: Island Dwarfism

For large animals, arriving on an island can be like moving into a tiny apartment after living on a sprawling ranch. The old rules no longer apply. On the mainland, being big is a huge advantage—it helps you fight off predators, compete for mates, and roam large distances for food. But on a resource-scarce island, a large body becomes a massive metabolic burden.

This is the primary driver of island dwarfism. The evolutionary logic is simple and ruthless:

- Fewer Resources: An island can’t support vast herds of massive herbivores. Individuals that are naturally smaller require less food, making them more likely to survive and reproduce when resources are scarce.

- Fewer Predators: Most islands lack large apex predators like lions, wolves, or sabre-toothed cats. Without this constant threat, the evolutionary pressure to maintain a large, defensive body size disappears. Being big is energetically expensive, and with no major predators to defend against, it’s a cost without a benefit.

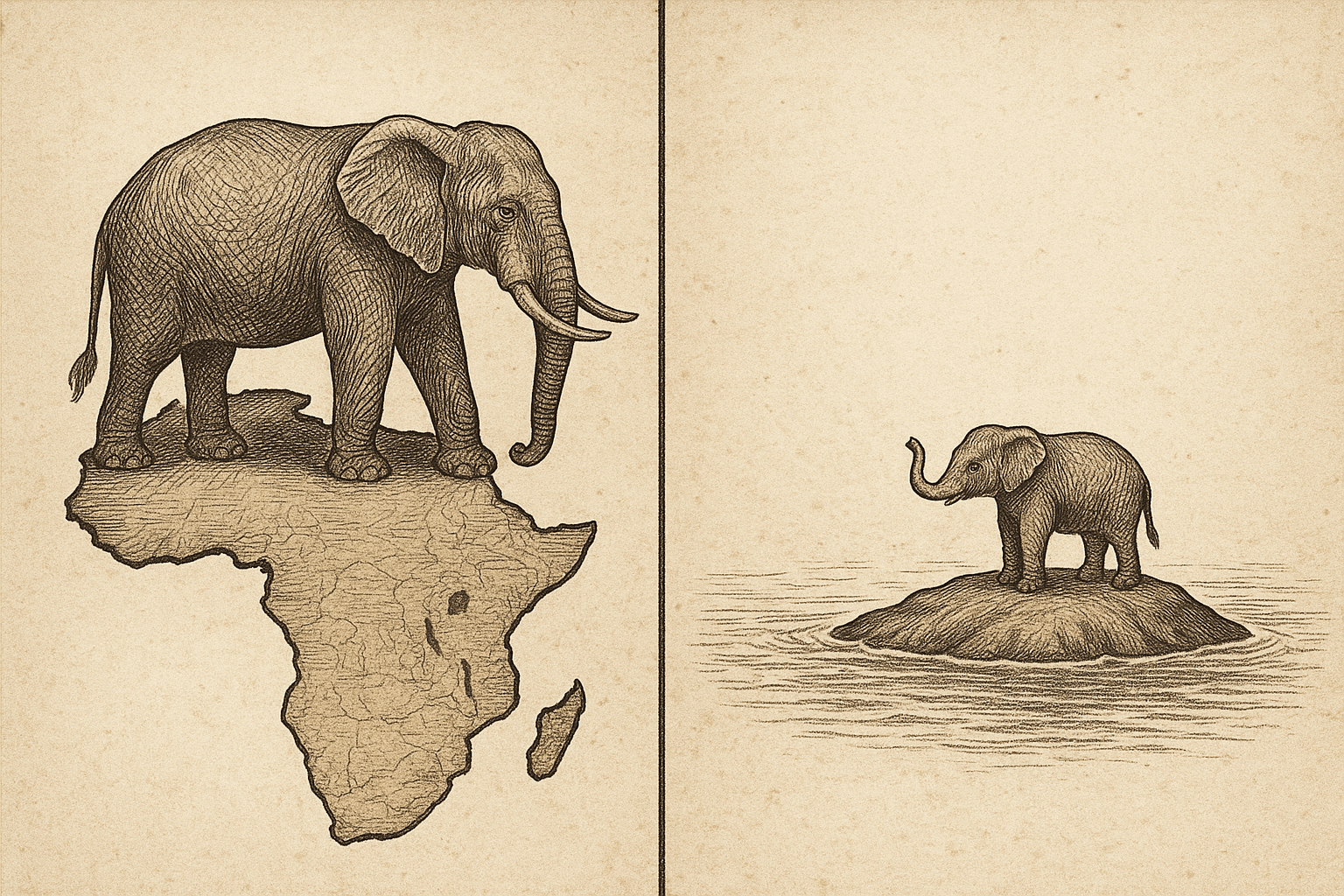

Spotlight: The Elephants of the Mediterranean

Perhaps the most stunning example of island dwarfism is found in the fossil record of the Mediterranean. During past ice ages, lower sea levels created land bridges, allowing mainland species, including straight-tusked elephants (*Palaeoloxodon antiquus*), to walk to islands like Sicily, Crete, Malta, and Cyprus. When the ice melted and sea levels rose, these populations became trapped.

Faced with limited vegetation and no large predators, the elephants began to shrink. The results were dramatic. On Sicily and Malta, the species *Palaeoloxodon falconeri* evolved to be just one meter (3.3 feet) tall at the shoulder and weigh around 300 kg (660 lbs)—a mere fraction of its 10-tonne mainland ancestor. These miniature elephants were perfectly adapted to their island homes, a testament to evolution’s efficiency. Similar stories played out with dwarf mammoths on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean and even, some scientists argue, with early hominins like *Homo floresiensis*—the “Hobbit”—on the Indonesian island of Flores.

The Rise of the Titans: Island Gigantism

While large animals shrink, the opposite often happens to small creatures. Small animals on the mainland, like rodents, lizards, and insects, live in a world filled with dangers. Everything from snakes and birds to weasels and foxes preys on them. Their small size and rapid reproductive cycle are their keys to survival.

When these small animals colonize an island, they often find themselves in a predator-free paradise. This phenomenon, known as “ecological release”, frees them from the evolutionary constraints that kept them small. With their primary predators gone, they can evolve to fill empty ecological niches, often those once occupied by the very predators that are now absent.

Spotlight: The Wētāpunga of New Zealand

Nowhere is island gigantism more apparent than in New Zealand. Aotearoa separated from the supercontinent Gondwana over 80 million years ago, and its ecosystem evolved in the complete absence of native land mammals (save for a few species of bats). This left many ecological roles wide open.

Enter the wētā. On the mainland, an insect of this type would be kept in check by small mammalian predators. But in pre-human New Zealand, the niche for a nocturnal, ground-dwelling forager—a role often filled by mice or shrews—was vacant. Wētā stepped up to fill it, and over millions of years, they grew. The giant wētā (*Deinacrida* species), or wētāpunga, is a true titan of the insect world. Some females can weigh over 70 grams, heavier than a finch, making them one of the heaviest insects on Earth. They became the “mice” of the New Zealand bush, a perfect example of a small creature expanding to fill a vacant role in an isolated environment. Other famous examples of gigantism include the Komodo dragon of Indonesia and the extinct Dodo of Mauritius, a giant, flightless pigeon.

Islands as Fragile Worlds

The “island rule” is not a strict law but a powerful trend that highlights the delicate balance between a species and its geographic space. It shows how evolution favors efficiency, dialing body size up or down to find the optimal fit for a given island’s resources and threats. The end products—dwarf elephants and giant insects—are marvels of adaptation.

However, this exquisite specialization is also their greatest weakness. Having evolved in isolation, these species are incredibly vulnerable to changes introduced by humans. The arrival of sailors brought rats, cats, and stoats to islands like New Zealand, which devastated native populations of giant wētā and flightless birds that had no defense against these new mammalian predators. The Dodo was hunted to extinction within a century of human arrival. These fragile worlds, once perfect laboratories for evolution, are now cautionary tales. They remind us that the unique geographic circumstances that create such wondrous life forms also make them exceptionally fragile in the face of global change.