The Lay of the Land: Shikoku’s Physical Geography

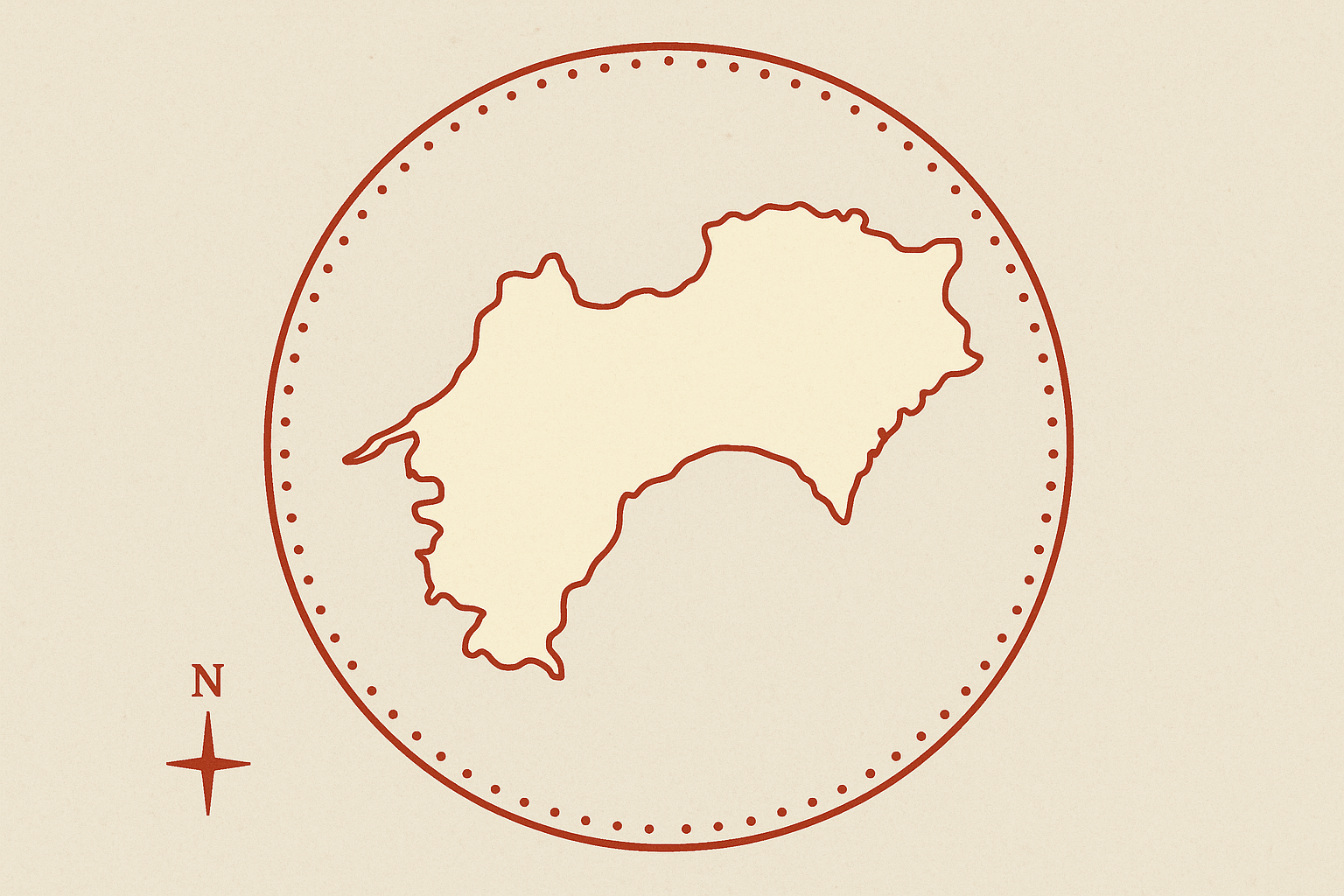

To understand the pilgrimage, one must first understand the island. Shikoku, Japan’s fourth-largest main island, is a place of dramatic physical contrasts. Its heart is dominated by a formidable range of east-to-west running mountains, with peaks like Mount Ishizuchi soaring to nearly 2,000 meters. This rugged, sparsely populated interior acts as a massive geographical barrier, effectively cleaving the island in two.

As a result, human settlement has historically clung to the narrow coastal plains. It is this fundamental physical geography that dictates the very shape of the pilgrimage. The 1,200-kilometer route is not a straight line but a practical, circumambulatory path that follows the contours of the land. It hugs the coastlines, dips into river valleys, and only crosses the mountains when absolutely necessary. The path’s existence is a testament to human adaptation, forcing travelers to engage with the island’s geography rather than conquer it.

Mapping Faith: The 88 Temples as Spatial Anchors

The Shikoku Henro is a man-made cultural landscape overlaid onto this physical canvas. The 88 temples are the sacred anchors of this landscape, the “dots” that the pilgrimage path connects. These temples are associated with the 9th-century Buddhist monk Kūkai, posthumously known as Kōbō Daishi, who was born on Shikoku. While the route has evolved over centuries, its purpose remains: to follow in his legendary footsteps.

The circular path is spiritually and geographically significant. With no official start or end, it represents the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, and the journey toward enlightenment. Traditionally, the pilgrimage is divided into four stages, each corresponding to one of Shikoku’s four prefectures and a stage of spiritual training.

- Tokushima (The Dōjō of Awakening): The journey begins here, with Temples 1 through 23. The geography is relatively gentle, following river valleys and coastal plains, allowing the pilgrim (known as an o-henro-san) to awaken to their purpose.

- Kōchi (The Dōjō of Austerity): This is the longest and most challenging section (Temples 24-39). The path stretches for hundreds of kilometers along the wild, typhoon-battered Pacific coastline. The immense capes and long distances between temples reflect the theme of ascetic training, demanding perseverance and resolve from the pilgrim. The geography itself becomes a tool for spiritual discipline.

- Ehime (The Dōjō of Enlightenment): Moving along the calmer Seto Inland Sea coast, this section (Temples 40-65) presents a varied landscape of coastal cities, rolling hills, and a few difficult mountain passes. This varied terrain mirrors the fluctuating path to enlightenment, with moments of clarity and struggle.

- Kagawa (The Dōjō of Nirvana): The final and shortest section (Temples 66-88) is located in Japan’s smallest prefecture. The terrain is flatter and more urbanized, and the temples are closer together. This final push symbolizes the attainment of nirvana, a state of peace and release, before the pilgrim completes the circle by returning to Temple 1.

Osettai: The Cultural Geography of Giving

Perhaps the most unique geographical phenomenon of the Henro is osettai. This is the deep-rooted cultural tradition of providing selfless gifts to pilgrims. It’s a practice that transforms the physical path into a corridor of extraordinary human generosity.

Residents of Shikoku view the o-henro-san not as strangers, but as representatives of Kōbō Daishi himself. By giving a pilgrim a small gift—a piece of fruit, a cold drink, a handful of coins, or even a free night’s stay—the giver is participating in the pilgrimage by proxy. They are making a spiritual offering and earning merit.

This transforms the human geography of the island. Osettai is a social support system mapped directly onto the physical route. You will find unattended huts (zenkonyado) stocked with snacks, benches built by locals for weary walkers, and farmers who stop their work to offer a piece of their harvest. This network of kindness is a tangible, geographical feature of the trail. It’s an infrastructure of compassion that has made this arduous journey possible for centuries, binding the pilgrims and the island’s inhabitants in a unique symbiotic relationship.

A Path in Motion: The Henro in the 21st Century

Today, the Shikoku Henro is a path in transition, a fascinating study in the collision of ancient and modern geography. While some sections remain as pristine, mossy forest trails snaking over mountains, many parts have been swallowed by asphalt. Pilgrims now walk along busy highways, through commercial city centers, and past modern train stations. They can choose to travel by foot, car, or tour bus, creating a diverse flow of people along the same sacred coordinates.

The human geography of the pilgrims themselves has also diversified. They are no longer just Japanese devotees, but also international hikers, spiritual seekers, and travelers drawn by the sheer cultural and physical challenge. The path has become a global landmark, a place where different cultures and motivations converge on a single, ancient line.

The Shikoku Pilgrimage is a powerful reminder that a landscape is never just rock and water. It is a story, a network, and a living map. On Shikoku, that map was drawn by a saint, is traced by pilgrims, and is held together by the geography of an island and the remarkable generosity of its people.