Imagine a river of air, invisible yet immensely powerful, flowing downhill under its own weight. This isn’t a scene from a fantasy novel; it’s a daily reality in many parts of our world. These are katabatic winds, a fascinating and formidable geographical phenomenon where gravity itself becomes the engine of the wind. From the icy desolation of Antarctica to the sun-baked canyons of California, these winds carve landscapes, influence climates, and profoundly shape human life.

The Science Behind the Flow

The term “katabatic” originates from the Greek word katabasis, meaning “descending.” This perfectly describes the process. The recipe for a katabatic wind is simple, relying on two key ingredients: elevation and cooling.

It begins on high-altitude landforms like plateaus, glaciers, or mountain ranges. During the night or the long polar winter, these surfaces lose heat rapidly through radiation, chilling the layer of air directly above them. Cold air is denser and heavier than warm air. As this pocket of cold, heavy air forms, it begins to sink and slide downslope, pulled by the simple, relentless force of gravity. It is, in essence, a drainage wind—air draining from the highlands to the lowlands.

As this river of dense air flows downwards, it can be channeled by valleys and canyons. Just as water speeds up through a narrow gorge, this air accelerates, sometimes reaching incredible speeds. This process makes katabatic winds some of the most consistently strong and gusty winds on the planet.

A Global Tour of Katabatic Winds

While the underlying physics is universal, katabatic winds manifest in unique and powerful ways across the globe, each with its own local name and character.

The Ferocious Winds of Antarctica

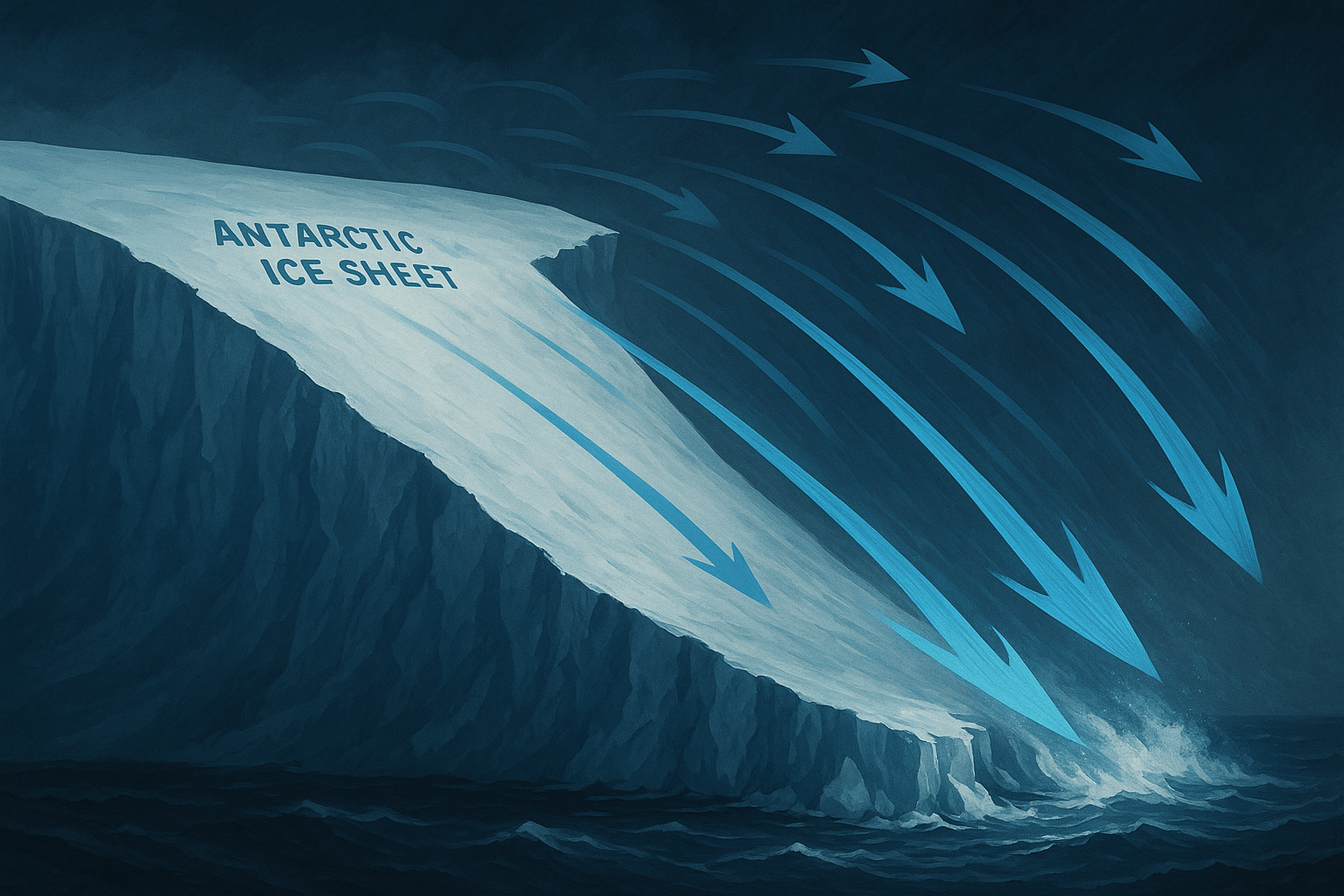

The undisputed king of katabatic winds reigns over the Antarctic continent. The vast, high-altitude East Antarctic Ice Sheet acts as the ultimate wind generator. The extreme cold of the polar night super-chills the air over this massive dome of ice, creating a permanent reservoir of incredibly dense air. This air constantly cascades off the plateau toward the coast.

These are not just breezes; they are the most powerful and persistent winds on Earth. Speeds regularly exceed 160 km/h (100 mph) and can gust over 300 km/h (190 mph). Locations like Cape Denison in Commonwealth Bay are famously cited as the windiest places on Earth at sea level, precisely because they lie at the bottom of a steep, icy slope that funnels these gravitational winds. For the scientists and staff living in research stations like McMurdo or Dumont d’Urville, these winds are a constant, dangerous reality that dictates all outdoor activity.

Greenland’s Piteraqs

The Greenland Ice Sheet, a smaller cousin to Antarctica’s, produces its own version of violent katabatic winds, known by the local Greenlandic name: Piteraq (meaning “that which ambushes you”). These sudden, hurricane-force winds typically plague the eastern coast of the island. Cold air builds up on the immense ice cap and then spills over the coastal mountains, accelerating dramatically as it plummets towards the sea. The town of Tasiilaq has historically suffered immense damage from Piteraqs, which can appear with little warning and flatten buildings not designed to withstand them.

Europe’s Mountain Winds: The Mistral and the Bora

Europe’s mountain ranges create several famous katabatic-type winds that have shaped regional culture and geography.

- The Mistral: In France, cold air pools over the snow-covered Massif Central and Alps. This dense air then surges south, funneling through the Rhône Valley between the two mountain ranges. The resulting cold, strong wind is known as the Mistral. It blasts through cities like Avignon and Marseille, often for days at a time, bringing clear skies but biting cold. Its influence is etched into the landscape of Provence, where rows of cypress trees are planted as windbreaks to protect crops.

- The Bora: On the other side of the Adriatic Sea, the Bora pours down from the Dinaric Alps of Croatia and Slovenia. It is a cold, notoriously gusty wind that slams into coastal cities like Trieste, Italy, and Split, Croatia. The Bora can be so strong that it closes bridges, halts ferry services, and sends sea spray far inland, coating everything in a layer of salt.

From California to the Columbia Gorge

North America has its own distinct and impactful katabatic winds, including one that is famously hot, not cold.

- The Santa Ana Winds: Southern California’s infamous Santa Ana winds are a special type of katabatic wind. The process begins with high-pressure air building over the high-altitude Great Basin deserts of Nevada and Utah. This cool, dense air begins to flow downslope towards the lower pressure of the Pacific coast. As it descends thousands of feet through mountain passes like the Cajon Pass, the air is dramatically compressed, causing it to heat up significantly (a process known as adiabatic heating) and its humidity to plummet. The result is a hot, desiccating, and powerful wind. This creates extreme fire danger, fanning small sparks into devastating infernos that threaten communities from Los Angeles to San Diego.

- Columbia Gorge Winds: Further north, a classic cold katabatic wind forms when frigid air from the high desert plateau east of the Cascade Mountains spills through the only sea-level break in the range: the Columbia River Gorge. The pressure differential between the cold interior and the milder coast drives a constant, powerful wind through this natural wind tunnel. This has had a profound human geography impact, transforming towns like Hood River, Oregon, into world-renowned capitals of windsurfing and kiteboarding.

Living with Gravity’s Breath

Katabatic winds are a powerful reminder of how physical geography dictates the terms of life. They present a dual nature: a source of peril and a source of opportunity.

On one hand, they pose significant risks. The Piteraqs of Greenland and the Bora of the Adriatic can cause widespread destruction. The Santa Anas are inextricably linked to California’s wildfire crises. In polar regions, they create some of the most inhospitable conditions on Earth. On the other hand, humanity has learned to adapt and even harness their power. The reliable winds of the Columbia Gorge have built a recreational economy, while the predictable Mistral has influenced centuries of agriculture and architecture. Increasingly, these steady wind corridors are being eyed for wind turbine farms, turning a force of nature into a source of renewable energy.

An Invisible Force Shaping Our World

From the world’s coldest continent to its most populated coastlines, katabatic winds are a fundamental force of nature. Driven by the simple trio of cooling, density, and gravity, they are an invisible river of air that flows across our planet. They chill cities, stoke fires, power sports, and define the very character of a place. The next time you feel a cold wind pouring out of a canyon on a clear night, you may be feeling the gentle sigh of a katabatic wind—gravity’s own icy breath, shaping the world in its path.