Look at a world map. The land is a vibrant tapestry of borders, cities, and countries. The oceans, however, are often just a vast, uniform blue. But this apparent emptiness is a geographic illusion. Beneath the waves lies a complex, invisible patchwork of boundaries, rights, and rules that govern over 70% of our planet. This intricate system is the work of one of the most significant yet under-appreciated international agreements in history: The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Often called the “constitution for the oceans”, UNCLOS, finalized in 1982, is a monumental achievement in human geography. It replaced a chaotic “might makes right” approach with a comprehensive framework for how nations can use the seas and their resources. It carves the ocean into distinct zones, each with its own set of rules, creating a legal geography that is every bit as real and consequential as the borders on land.

The Zones: How the Ocean is Divided

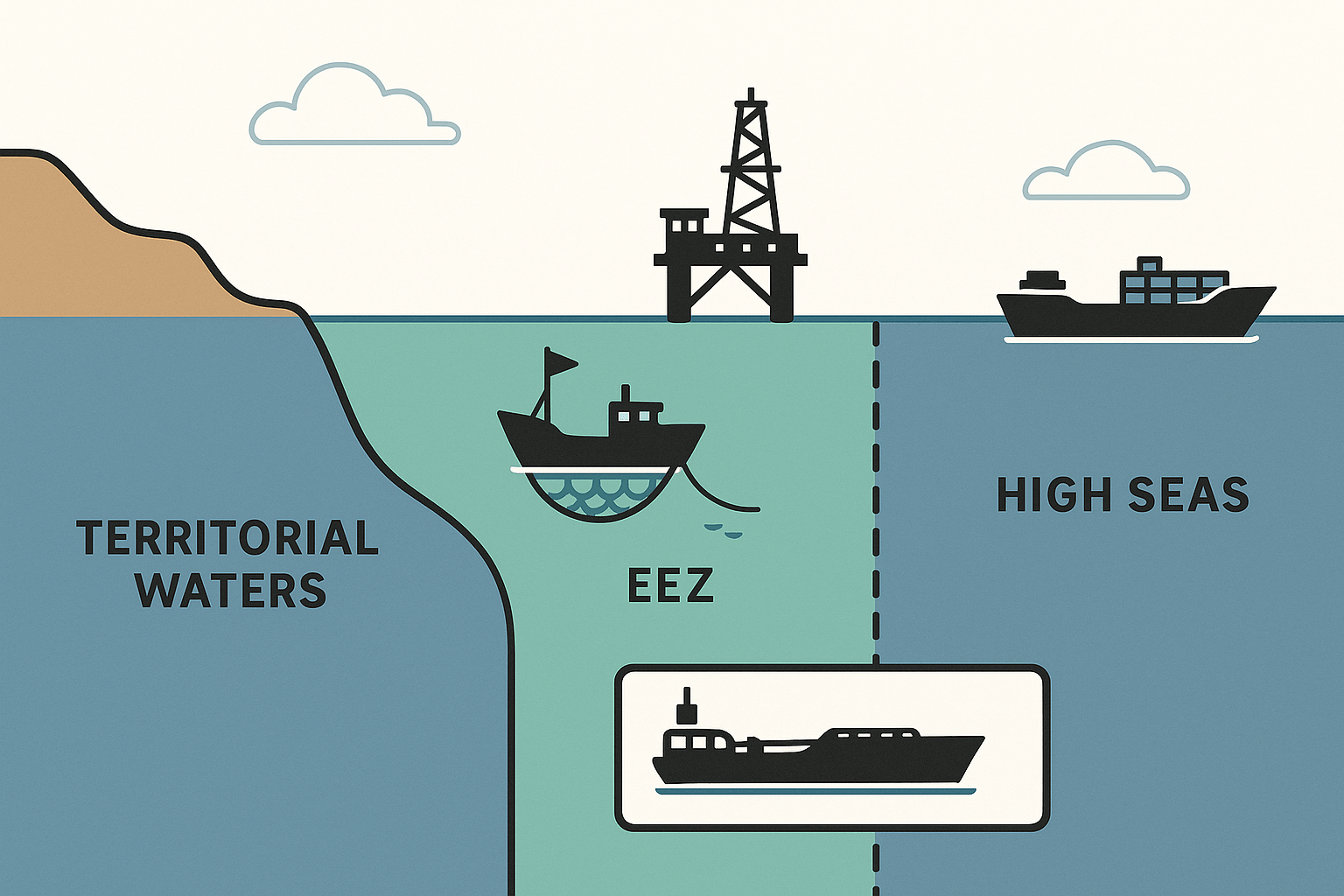

UNCLOS draws its lines starting from a country’s baseline, which is typically the low-water line along its coast. For archipelagic nations like Indonesia or the Philippines, straight baselines can be drawn to connect the outermost points of their outermost islands. From this baseline, the maritime zones extend outward like concentric rings.

Territorial Sea: An Extension of Sovereignty

Extending 12 nautical miles (about 22 km) from the baseline, the Territorial Sea is the zone where a coastal state’s sovereignty is strongest. The laws of the country apply fully here, just as they do on land. Foreign vessels, however, are granted the right of “innocent passage”, meaning they can transit through these waters as long as their activity is not prejudicial to the “peace, good order or security of the coastal State.” What constitutes “innocent” can be a point of contention, especially when warships navigate sensitive chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz.

Contiguous Zone: The Buffer Zone

Stretching from 12 to 24 nautical miles (44 km) from the baseline, the Contiguous Zone acts as a buffer. Here, a state doesn’t have full sovereignty, but it can enforce its laws in four specific areas: customs, taxation, immigration, and pollution. Think of it as a nation’s front yard—they can act to prevent or punish infringement of their laws that occurs within their territory or territorial sea.

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ): The Resource Jackpot

This is where the geography of the ocean gets truly interesting and contentious. The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends up to 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the baseline. Within its EEZ, a coastal state has sovereign rights (a crucial distinction from sovereignty) for the purpose of exploring, exploiting, conserving, and managing all natural resources. This includes:

- Living resources: Fish stocks, which form the backbone of many national economies.

- Non-living resources: Vast reserves of oil and natural gas on and under the seabed.

- Energy production: The potential for harnessing wind, wave, and current power.

The concept of the EEZ dramatically reshaped the world map. Suddenly, tiny islands in the middle of nowhere became incredibly valuable, granting the nations that own them control over immense swathes of ocean. This is why France, thanks to its scattered overseas territories like French Polynesia and New Caledonia, has the largest EEZ in the world, followed closely by the United States.

Where the Lines Blur: Geopolitical Hotspots

While UNCLOS provides a framework, it doesn’t automatically solve disputes, especially when geography is complex and historical claims clash. The invisible lines of the EEZ are the front lines of modern geopolitical rivalry.

The South China Sea: A Tangle of Claims

Perhaps no place on Earth better illustrates the tensions of maritime law than the South China Sea. Here, China’s expansive “nine-dash line” claim overlaps with the internationally recognized EEZs of Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia. The conflict centers on control of vital shipping lanes and potential resource wealth. The geography itself is a point of contention: Are the Spratly and Paracel features islands capable of generating their own EEZs, or are they mere rocks or low-tide elevations with no such rights? A 2016 international tribunal ruled against many of China’s claims, a landmark decision based on UNCLOS principles, but one that Beijing has rejected, leading to a tense and militarized status quo.

The Arctic Ocean: A New Frontier Unfrozen

As climate change melts the polar ice cap, the physical geography of the Arctic is transforming, opening up a new arena for maritime claims. For centuries, the Arctic Ocean was an impassable frozen wasteland. Now, new shipping routes like the Northwest Passage (through the Canadian archipelago) and the Northern Sea Route (along Russia’s coast) are becoming viable. More importantly, vast, untapped oil, gas, and mineral resources are thought to lie beneath the Arctic seabed. Coastal states—Russia, Canada, the USA (via Alaska), Denmark (via Greenland), and Norway—are scrambling to map their continental shelves to submit claims under UNCLOS for seabed rights extending far beyond their 200-nautical-mile EEZs. The Lomonosov Ridge, a massive underwater mountain range stretching across the pole, is at the center of overlapping claims by Russia, Canada, and Denmark, each arguing it is a natural extension of their continental landmass.

The Eastern Mediterranean: Islands and Energy

The discovery of significant natural gas fields has turned the waters between Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, and Egypt into another hotspot. The dispute here is complicated by geography and politics. Greece argues that its thousands of islands, even small ones like Kastellorizo just off the Turkish coast, should generate their own full EEZs, effectively boxing in Turkey’s maritime access. Turkey, which is not a signatory to UNCLOS, disputes this interpretation and has pursued its own drilling activities based on a rival maritime deal with Libya. The result is a complex web of competing claims that threatens regional stability.

The Future of Ocean Governance

The Law of the Sea is not a static document. It’s a living framework that continues to shape our world. As technology allows for deep-sea mining and sea levels rise, threatening to submerge the very baselines from which zones are measured, UNCLOS faces new tests. A new, legally binding treaty under UNCLOS was recently agreed upon to protect biodiversity in the High Seas—the vast areas beyond any national jurisdiction that are considered the “common heritage of all mankind.”

The lines drawn by UNCLOS may be invisible, but their impact on global trade, resource management, and international security is profound. They remind us that the world’s oceans are not a featureless void, but a critical geopolitical space, governed by rules that are constantly being tested, interpreted, and fought over on our ever-changing planet.