In a world where gold, diamonds, and oil have long dominated the narrative of natural resources, there lies a small, landlocked nation in Southern Africa whose most valuable export is entirely different. It’s clear, life-sustaining, and increasingly precious: fresh water. This is Lesotho, the “Kingdom in the Sky,” and its story is a fascinating case study in how geography can dictate a nation’s destiny. Lesotho’s mountains don’t just touch the clouds; they capture them, turning the country into a vast natural water tower for its parched, powerful neighbor, South Africa.

The Tale of Two Geographies

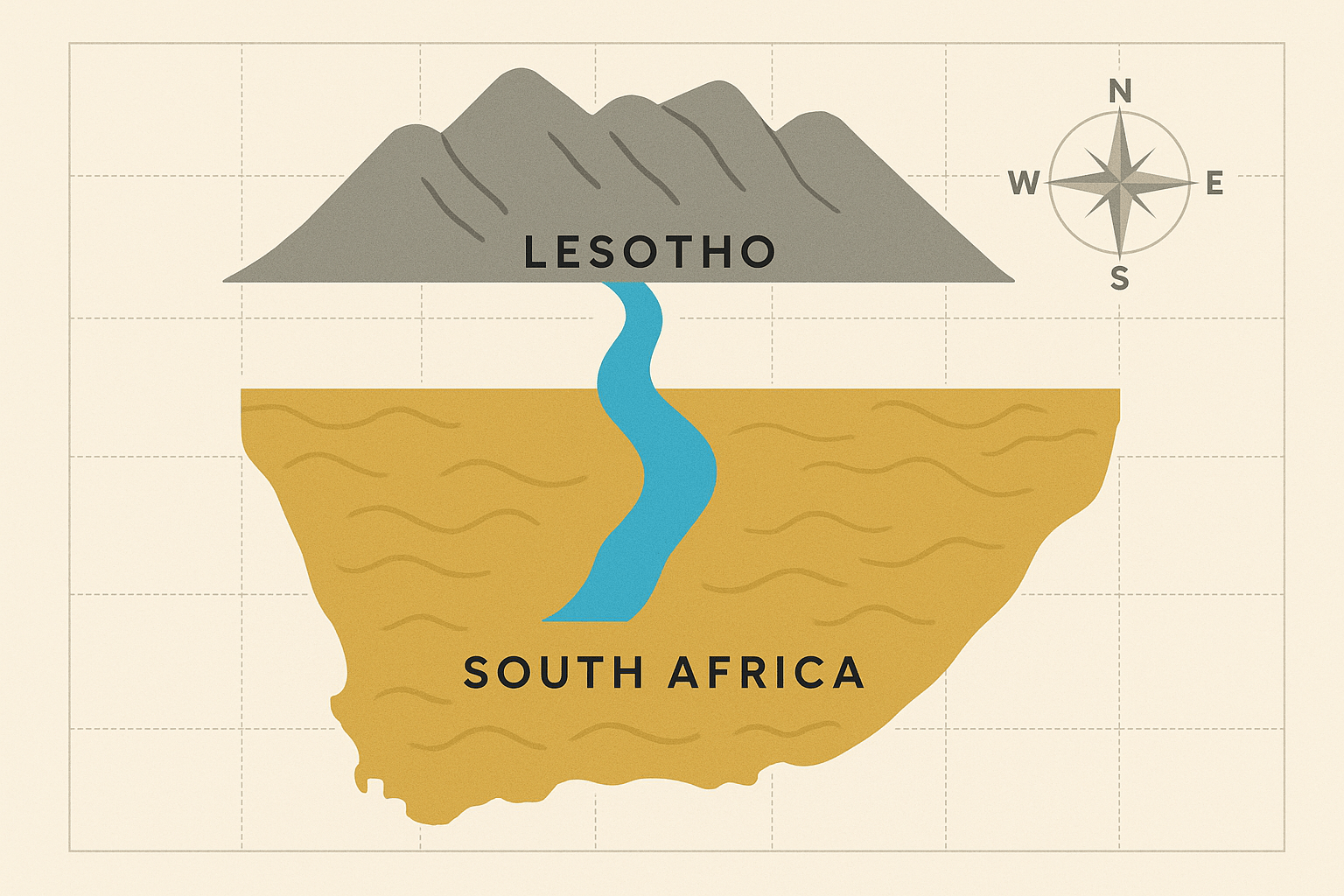

To understand this unique relationship, you must first appreciate the stark geographical contrast between these two countries. Lesotho is a geological anomaly. It is the only independent state in the world that lies entirely above 1,000 meters (3,281 ft) in elevation. Its rugged landscape is dominated by the soaring peaks of the Maloti and Drakensberg mountain ranges. This high altitude acts as a formidable barrier to moisture-laden air, forcing it to rise, cool, and release its contents as rain and snow. The result is a country with abundant water resources, channeled into a network of pristine rivers like the Senqu (which becomes the Orange River in South Africa), carving deep valleys perfect for storing this liquid bounty.

Now, cast your eyes just across the border to South Africa’s Gauteng province. This is the nation’s economic heartland, a sprawling urban conglomeration that includes Johannesburg and Pretoria. It generates over a third of South Africa’s GDP and is home to more than 15 million people. But geographically, it has a problem. Gauteng is located on a high, relatively dry plateau, far from major natural water sources. Its massive population, thirsty industries, and historic gold mines demand far more water than the local Vaal River system can reliably provide. It is a powerhouse running on an empty tank.

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project: Engineering on a Grand Scale

This geographical imbalance set the stage for one of the most ambitious engineering feats in African history: the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP). Conceived over decades and formalized by a treaty in 1986, the LHWP is a multi-phase, multi-billion-dollar megaproject designed to solve South Africa’s problem by harnessing Lesotho’s advantage.

The project is a marvel of human ingenuity. It involves:

- Massive Dams: Towering concrete structures like the Katse Dam (one of the highest in Africa) and the Mohale Dam have created vast, deep reservoirs in the heart of the Maloti mountains, fundamentally reshaping the landscape.

- Interconnecting Tunnels: A network of tunnels, some over 80 kilometers long, has been bored directly through the mountains. These subterranean aqueducts act as arteries, gravity-feeding water from the full reservoirs in Lesotho northwards to South Africa.

- Hydropower Generation: A secondary, but crucial, benefit for Lesotho is the ‘Muela Hydropower Station, which uses the transferred water to generate electricity for the nation, reducing its near-total dependence on South Africa for power.

The completed Phase I of the project now delivers approximately 780 million cubic meters of water to South Africa annually. Phase II, currently underway with the construction of the Polihali Dam, will increase this capacity even further, underscoring the long-term nature of this hydro-dependency.

“White Gold” and the Politics of Hydro-Hegemony

This immense transfer of a vital resource is often called a story of “white gold.” For Lesotho, the royalties from water sales are a cornerstone of the national economy, constituting a significant portion of government revenue. The LHWP brought roads, power lines, and jobs to remote mountain communities. Yet, this golden opportunity is not without its tarnish.

The relationship between Lesotho and South Africa is a textbook example of hydro-hegemony. This is a geopolitical term describing a power imbalance where a dominant, downstream country (the hegemon) exerts significant control over water resources shared with a less powerful, upstream neighbor. South Africa, with its vastly larger economy and military, is the undisputed regional hegemon. While Lesotho holds the geographical upper hand—the “water tap”, so to speak—its economic and political reliance on South Africa creates a complex and unequal partnership.

The costs for Lesotho have been significant.

- Displacement and Social Disruption: The creation of the reservoirs flooded thousands of hectares of fertile valley-bottom land, the most productive agricultural areas in the mountains. Thousands of Basotho villagers were displaced from their homes and ancestral lands, their pastoral way of life irrevocably altered.

- Environmental Impacts: Damming the rivers has changed downstream ecosystems, affecting biodiversity and traditional river use. The promise of compensation and development for affected communities has been a fraught process, with many feeling they were left behind by the wave of progress.

- Questions of Sovereignty: The 1986 treaty, signed during South Africa’s apartheid era, has been a source of ongoing debate. Critics argue that the terms disproportionately favor the water-scarce giant, leaving Lesotho in a vulnerable position. Can a nation be truly sovereign when its most critical natural resource is contractually bound to the needs of its neighbor?

A Symbiotic, if Uneasy, Future

Every day, water from the Lesotho highlands flows through mountain tunnels and into the Vaal Dam, quenching the thirst of Johannesburg’s industries and sustaining South Africa’s economic lifeblood. This flow represents a complex symbiosis born of geographical necessity. Lesotho receives vital revenue and electricity; South Africa receives the water it cannot survive without.

But it is a precarious balance. As climate change threatens more erratic rainfall patterns and an increasingly water-stressed future for Southern Africa, the value of Lesotho’s “white gold” will only rise. This will undoubtedly intensify the political, economic, and environmental pressures on the Kingdom in the Sky. The story of Lesotho’s water is more than just geography and engineering; it is a profound lesson in power, dependency, and the price of a planet’s most essential resource.