Imagine setting out on a journey from the icy shores of Greenland to the frozen expanse of Antarctica, a round trip of over 70,000 kilometres, and navigating it with unerring precision. Now imagine you are an Arctic Tern, weighing barely more than a smartphone. Or picture yourself as a newly hatched Loggerhead turtle, plunging into the vast Atlantic off the coast of Florida and spending years navigating the massive North Atlantic Gyre before returning to the very region you were born. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the daily reality for millions of creatures, and their secret lies in an incredible sixth sense: magnetoreception.

The Earth’s Invisible Atlas

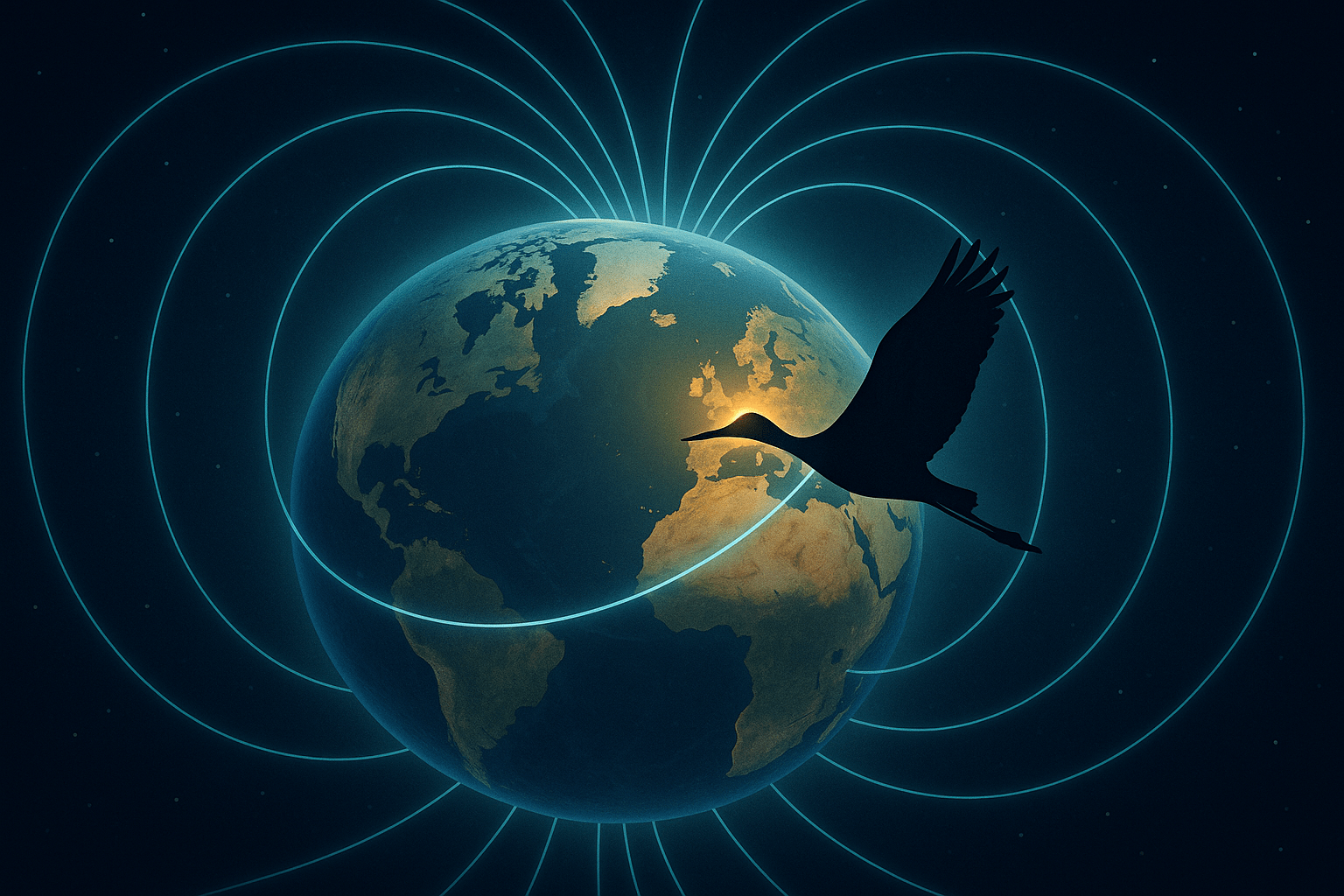

To understand this biological superpower, we must first look at the geography of our planet on a scale we cannot see. The Earth isn’t just a sphere of rock and water; it’s a giant magnet. Deep within its core, the churning of molten iron generates a powerful magnetic field that envelops the globe, stretching from the magnetic North Pole to the South Pole. This field is our planet’s invisible shield, protecting us from solar radiation, but for many animals, it’s also an intricate, reliable map.

This “magnetic atlas” has features just like a physical one:

- Direction (Polarity): Just like a handheld compass needle, the field lines provide a clear north-south axis.

- Inclination Angle: The angle at which the magnetic field lines intersect the Earth’s surface changes with latitude. The lines are parallel to the ground at the magnetic equator and point straight down at the magnetic poles. This provides a reliable indicator of how far north or south you are.

- Intensity: The strength of the magnetic field also varies predictably across the globe, generally being strongest at the poles and weakest at the equator. This adds another layer of locational data.

For an animal that can perceive these three elements, the world is overlaid with a geographical grid that provides both a compass for direction and a map for pinpointing its specific location.

Masters of Migration: The Global Trekkers

The ability to read this magnetic map is found across the animal kingdom, enabling some of the most spectacular journeys in the natural world. Each species uses it in a way perfectly suited to its own unique geography.

The Arctic Tern: A Pole-to-Pole Odyssey

The Arctic Tern holds the record for the longest migration. These birds breed in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of North America, Europe, and Asia during the northern summer. When winter approaches, they don’t just fly south; they embark on a staggering journey to the Weddell Sea on the coast of Antarctica. By following the magnetic field, they navigate over open oceans and across continents, a feat of endurance and navigation that is almost impossible to comprehend.

The Loggerhead Turtle: Riding the Ocean’s Magnetic Highways

Sea turtles are born with a magnetic “imprint” of their home beach. When Loggerhead hatchlings scurry from their nests in Florida into the Atlantic, they immediately use their magnetic sense to find the North Atlantic Gyre. This enormous, circulating ocean current acts as a conveyor belt, rich in food. For years, the turtles use the magnetic field’s varying intensity and inclination to stay within the gyre’s safe, productive waters, effectively navigating a moving, continent-sized habitat. When it’s time to breed, they use that same magnetic signature to navigate back across thousands of kilometres of open ocean to the very region where their journey began.

The Salmon’s Uncanny Homecoming

The story of the salmon is one of incredible fidelity. After years in the open ocean, a Chinook salmon can navigate back not just to the correct continent, not just to the correct coastline, but to the specific river system—like the Fraser River in Canada or the Columbia River in the United States—where it hatched. While the final leg of the journey is guided by an acute sense of smell, scientists believe that magnetoreception is what gets them into the right coastal area from the vast Pacific, using the Earth’s field as a large-scale map to find the starting point of their olfactory trail.

How Do They Read the Map?

The question of how animals see this invisible world is a frontier of scientific research. While we don’t have all the answers, two leading theories have emerged.

The first, known as the Radical-Pair Mechanism, is thought to be used by birds. It proposes that a protein called cryptochrome in the bird’s retina reacts to light in a way that is sensitive to the magnetic field. This could create a visual pattern that is superimposed over the bird’s normal vision—a kind of biological “heads-up display” that makes the magnetic field visible, allowing the bird to literally see the direction to fly.

The second theory involves tiny, biological particles of a magnetic mineral called magnetite. Found in the cells of animals like sea turtles and salmon, these particles act like microscopic compass needles. As the animal moves, these magnetite crystals twist and pull on receptors connected to the nervous system, providing real-time information about the direction, angle, and strength of the local magnetic field.

A Shifting World: Navigation in the Anthropocene

This ancient navigational system is now facing modern challenges. The spread of human technology has created a form of “electromagnetic smog.” Power lines, cell towers, and radio signals create their own magnetic fields. Studies have shown that some birds become disoriented when flying over urban centres, suggesting our digital world may be interfering with their natural GPS.

Furthermore, the Earth’s geography itself is not static. The magnetic North Pole is on the move. For centuries, it was located in northern Canada, but it is now drifting rapidly across the Arctic Ocean towards Siberia. For animals that have relied on a stable magnetic map for millennia, this is a significant geographical shift. Will their internal maps recalibrate? Will ancient migratory routes be redrawn? These are urgent questions for conservationists as our planet continues to change.

An Unseen World of Information

Magnetoreception reminds us that our human-centric view of the world, with its cities, borders, and roads, is just one interpretation of the planet. For countless animals, the Earth is a landscape of invisible forces and pathways. It’s a world where a mountain range might be less of a barrier than a change in magnetic intensity, and a home beach is not a point on a map, but a unique magnetic address. This incredible sense reveals a layer of geography that is profound, elegant, and woven into the very fabric of life itself.