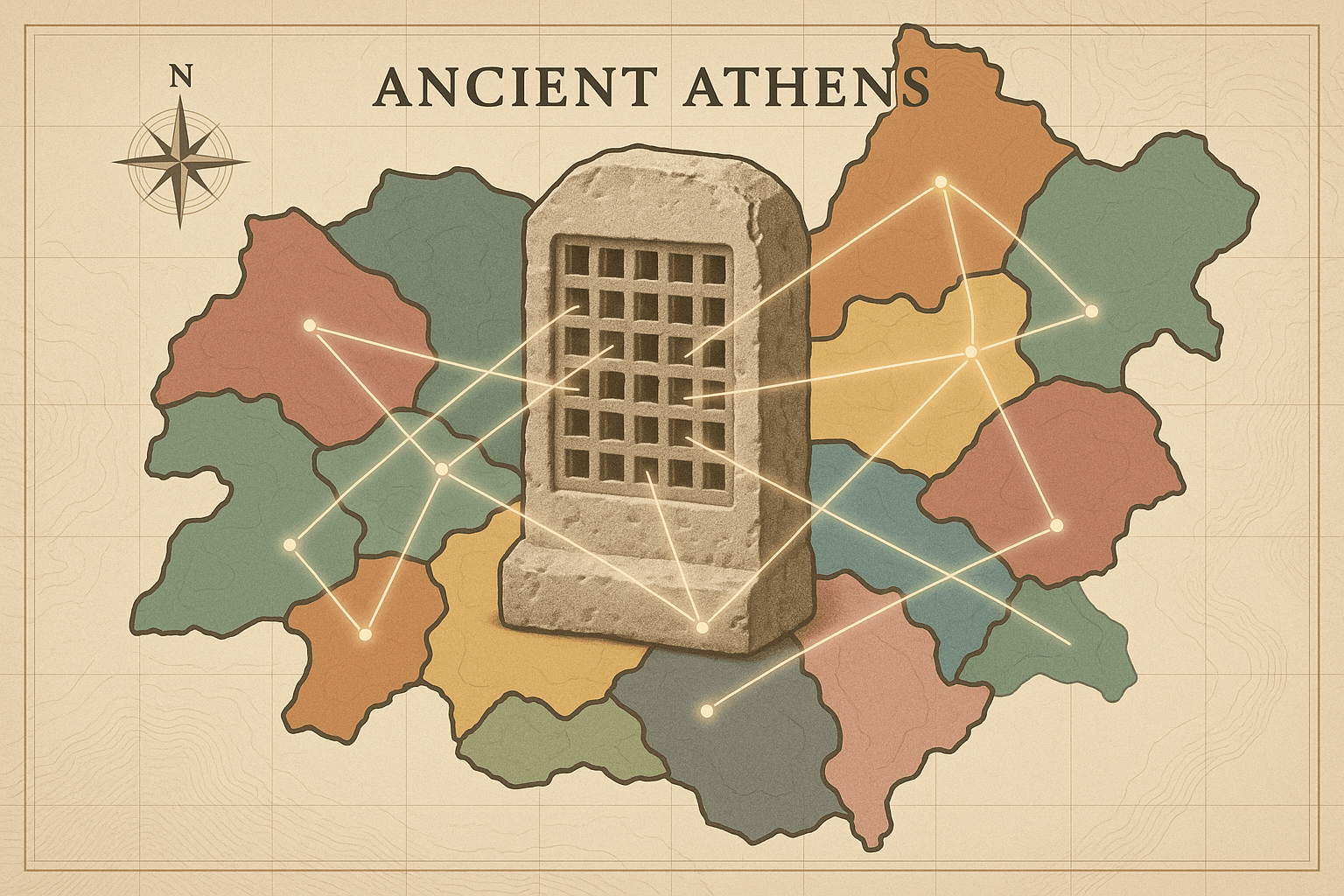

Imagine standing in the bustling heart of ancient Athens, the Agora. It’s a chaotic symphony of merchants hawking their wares, philosophers debating in shaded colonnades, and citizens hurrying to the business of the state. It was here, in the cradle of democracy, that power was distributed not by wealth, lineage, or even popular vote, but by the cold, impartial logic of a stone slab and a handful of dice. This device was the kleroterion, and its purpose was to randomize political selection. But this wasn’t just a lottery; it was a sophisticated tool of geographical engineering, designed to answer a fundamental question: in a sprawling city-state like Attica, how do you ensure a farmer from an inland village has the same shot at power as a wealthy merchant from the city center?

The kleroterion was the answer. It wasn’t just a machine for choosing people; it was a machine for mapping political opportunity, ensuring that the geography of power reflected the geography of the people themselves.

A Stone Machine for an Ironclad Democracy

At first glance, a kleroterion looks like a bizarre, misplaced game board. It’s a rectangular slab of stone, carved with neat rows of slots. Found in the Athenian Agora, these relics are the physical embodiment of Athens’ radical trust in its citizenry. The process was a masterpiece of anti-corruption design.

Here’s how it worked:

- The Citizen’s ID: Each citizen who wished to be considered for a public office (like serving on the city council or as a juror) possessed a small bronze or wooden ticket called a pinakion. It was inscribed with his name, his father’s name, and his home district, or deme. It was his official, state-issued ID card.

- Filling the Slots: On the day of selection, eligible candidates would arrive and insert their pinakia into the slots (kleroi) on the kleroterion. Each column of slots was assigned to one of Athens’ ten tribes.

- The Randomizer: A hollow tube was fixed to the side of the stone. An official would pour a mix of black and white dice (or marbles) into a funnel at the top. The dice would stack randomly inside the tube.

- The Moment of Truth: A crank at the bottom of the tube would release one die at a time. If a white die emerged, the entire corresponding horizontal row of citizens—one from each tribe—was selected for office. If a black die emerged, the entire row was dismissed. This continued until all the required positions were filled.

The beauty of this system was its incorruptibility. You couldn’t bribe a random die. You couldn’t influence a stone slab. It was a purely mechanical process that removed human bias, wealth, and influence from the equation. But its true genius lay in how it interacted with the very map of Attica.

The Geographic Architecture of Athens

To understand the kleroterion’s spatial magic, we must first understand the political geography of Athens, brilliantly re-engineered by the reformer Cleisthenes in 508/507 BCE. Before Cleisthenes, Athenian politics were dominated by powerful aristocratic clans who controlled specific territories. To break their power, he didn’t just rewrite laws; he redrew the map.

Cleisthenes divided the citizenry based on three distinct geographical regions:

- The City (Asty): The urban core of Athens and its immediate surroundings.

- The Coast (Paralia): The coastal areas, including the vital port of Piraeus.

- The Inland (Mesogeia): The agricultural plains and rural heartland of Attica.

He then broke down the population into new administrative units:

- Demes: The smallest unit, a local village or city neighborhood. This became a citizen’s core identity. Socrates, for example, was from the deme of Alopece.

- Trittyes: Cleisthenes grouped the demes into 30 “thirds”, or trittyes. Crucially, there were 10 trittyes for each of the three geographical regions (10 city, 10 coastal, 10 inland).

- Phylai (Tribes): Finally, he created 10 new tribes, the fundamental units for organizing the military and the government. And here is the masterstroke: each tribe was a composite, made up of three trittyes, one from the city, one from the coast, and one from the inland region.

Think of each tribe as a perfect geographical cross-section of Attica. It wasn’t a contiguous territory but a political collage, intentionally stitching together the interests of urbanites, sailors, and farmers. This structure made it impossible for any single region to dominate a tribe’s politics.

Where Machine Meets Map: Enacting Spatial Fairness

Now, let’s bring the kleroterion back into the picture. The device didn’t operate on a city-wide free-for-all. It worked in concert with Cleisthenes’ geographic system.

The best example is the selection of the Boule, or Council of 500, which set the daily agenda for Athens. The Council was composed of 50 citizens from each of the 10 tribes. The number of council seats assigned to each deme was proportional to its population. So, a large deme might put forward eight candidates, while a tiny one might put forward only one.

On selection day, all the candidates from the demes belonging to a single tribe would present themselves. Let’s say the “Erechtheis” tribe needed to select its 50 councilors. The candidates from its city trittys, its coastal trittys, and its inland trittys would all place their pinakia into the slots of the kleroterion. The machine would then be cranked, and the white and black dice would fall.

The randomness of the kleroterion ensured that within that pool of tribally-approved candidates, the selection was utterly impartial. But the structure of the tribe itself guaranteed geographic diversity. Because the tribe was a forced coalition of city, coast, and country, the random selection was drawing from a pool that was *already* geographically balanced. The kleroterion wasn’t creating fairness from scratch; it was ratifying and enacting the spatial fairness already hardwired into the political map.

A Map of Distributed Opportunity

This system created a political landscape fundamentally different from our own. Where modern democracies often struggle with gerrymandering—the drawing of electoral maps to favor one group—Athens used geography to enforce impartiality. The kleroterion was the final, crucial step in a process designed to:

- Shatter Regional Factions: A politician on the Council couldn’t just serve the interests of his fellow farmers, because his tribal colleagues were fishermen and city merchants. To get anything done, they had to find common ground.

- Forge a Unified Identity: By forcing citizens from different landscapes and livelihoods to work together, the system fostered a broader Athenian identity. It transformed parochial concerns into shared civic responsibility.

- Guarantee Spatial Equity: It ensured that a citizen’s home address wasn’t a barrier to political participation. The stone slab in the Agora projected a map of opportunity that reached into the furthest mountain villages and coastal fishing ports of Attica.

The logic of the kleroterion was therefore a geographical one. It was an elegant solution to the perennial problem of central versus peripheral power. It tells a story not just of a belief in the wisdom of ordinary citizens, but of a profound understanding that a democracy’s health depends on its ability to connect every corner of its territory to the heart of its government. That strange, slotted stone was more than a lottery machine; it was the guardian of a truly representative map.