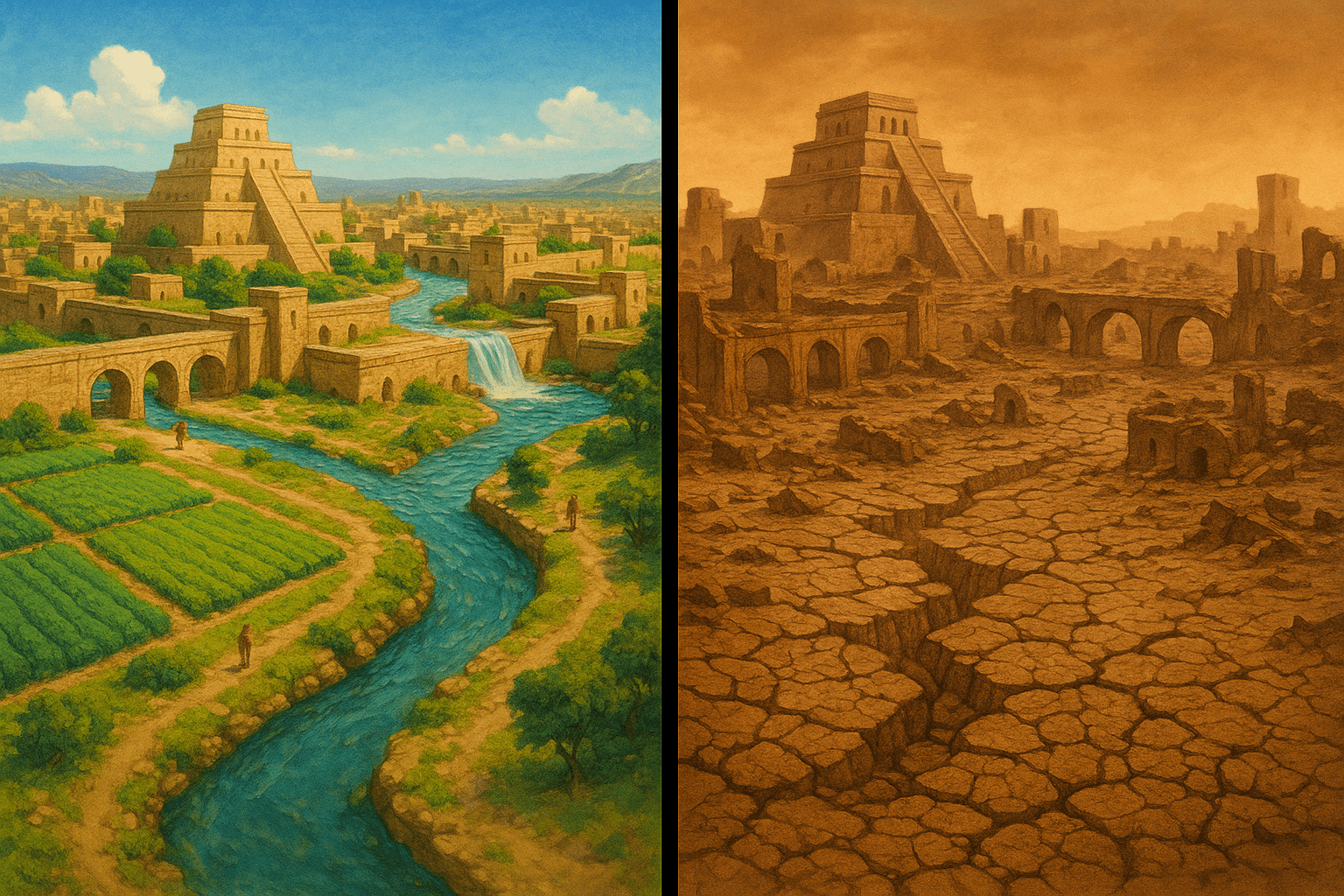

Wander through the silent, sun-baked ruins of a place like Mesa Verde in Colorado or the jungle-choked plazas of Tikal in Guatemala, and an unavoidable question hangs in the air: Why? Why would a thriving, sophisticated society abandon the magnificent cities they spent centuries building? While historians point to complex factors like warfare, disease, and political strife, geographers and paleoclimatologists are uncovering a powerful, often-overlooked catalyst: climate change, specifically in the form of the “megadrought.”

These weren’t your typical dry spells. A megadrought is a drought of exceptional severity and duration, lasting for multiple decades, sometimes even centuries. They are climatic monsters, capable of fundamentally reshaping landscapes and breaking the back of even the most resilient civilizations. To understand their impact, we must become climate detectives, following clues hidden in tree rings, lakebeds, and caves.

Whispers from the Past: The Science of Paleoclimatology

How can we possibly know what the rainfall was like 1,000 or 4,000 years ago? The answer lies in the field of paleoclimatology—the study of past climates. Scientists use natural archives, or “proxies”, to reconstruct ancient weather patterns with astonishing detail.

- Tree Rings (Dendrochronology): In dry regions, the width of a tree’s annual growth ring is a direct indicator of that year’s precipitation. A long sequence of narrow rings points to a prolonged drought.

- Lake and Ocean Sediments: Each year, layers of sediment settle at the bottom of lakes and oceans. By drilling cores, scientists can analyze the chemical composition of these layers. For example, the types of pollen reveal the dominant plant life, while the amount of gypsum or the saltiness of fossilized shells can indicate how much a lake evaporated.

- Cave Formations (Speleothems): The chemical makeup of stalagmites and stalactites changes based on the amount of rainwater seeping into the cave. Analyzing these layers provides a high-resolution record of rainfall.

These proxies are our time machines. They allow us to pinpoint periods of extreme climate stress and overlay them onto the timeline of human history, revealing a startling correlation between megadroughts and societal collapse.

The Akkadian Empire: Collapse in the Fertile Crescent

Our first stop is Mesopotamia, the “land between the rivers”, specifically the area of modern-day Iraq and Syria. Here, around 2334 BCE, the Akkadian Empire rose to become arguably the world’s first empire. Its power was built on the agricultural bounty of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Yet, just over a century later, this mighty empire crumbled into dust.

For decades, the cause was a mystery. But paleoclimatological evidence points to a prime suspect: the 4.2 kiloyear aridification event. Sediment cores drilled from the Gulf of Oman show a dramatic and sudden spike in wind-blown dust originating from Mesopotamia right around 2200 BCE. This indicates a catastrophic shift in climate—a megadrought that lasted for up to 300 years.

The geographic implications were devastating. The reliable rains that fed northern Akkadian agriculture failed. The flow of the great rivers likely diminished. The once “Fertile Crescent” was choked by dust storms and crop failure. The result? Widespread famine, mass migration of desperate people towards the south, and the breakdown of the central authority that held the empire together. The world’s first empire may have been one of climate’s first major casualties.

The Classic Maya: A Thirst in the Rainforest

Moving forward in time and across the globe, we arrive in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico and Central America. Between 250 and 900 CE, the Classic Maya civilization flourished, building spectacular city-states like Tikal, Calakmul, and Copán. They were master astronomers, mathematicians, and engineers, developing sophisticated water management systems—including vast reservoirs and reliance on natural sinkholes called cenotes—to survive the seasonal tropical dry periods.

But their ingenuity couldn’t save them from the Terminal Classic Collapse. Beginning around 800 CE, one by one, the great southern cities were abandoned. The monuments fell silent, and the jungle began its slow reclamation.

Again, climate records tell the story. Sediment cores from Lake Chichancanab in the Yucatán and speleothem data from regional caves reveal that this period was marked by a series of intense, multi-decade droughts. Analysis suggests that annual rainfall may have decreased by as much as 40-70% during the peak drought periods. For a civilization whose entire agricultural and social calendar revolved around the maize crop and predictable rainfall, this was apocalyptic. The reservoirs ran dry, crops failed repeatedly, and the delicate balance of power shattered as city-states likely went to war over ever-dwindling resources, leading to a cascade of societal failure.

The Ancestral Puebloans: An Exodus from the Cliffs

Our final case study takes us to the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. Here, the Ancestral Puebloan people built breathtaking cliff dwellings like those at Mesa Verde and massive “great houses” in Chaco Canyon. From roughly 900 to 1250 CE, they developed a complex society based on dryland farming of maize, beans, and squash in a challenging semi-arid environment.

Then, in the late 13th century, they left. They systematically emptied their cliff palaces and migrated south and east towards more reliable water sources like the Rio Grande. The reason is etched into the very wood they used to build their homes.

The tree-ring record from this region is one of the most complete in the world, and it speaks clearly of a devastating megadrought. Known as the “Great Drought”, this period from 1276 to 1299 CE saw two decades of relentlessly brutal, below-average rainfall. For a society already living on the edge, this was the final push. The drought, likely coupled with resource depletion and social conflict, made their agricultural way of life in the high plateaus untenable. The great migration wasn’t an invasion or a single event, but a rational response to a catastrophic environmental shift.

Lessons Etched in Stone and Dust

From the plains of Syria to the cliffs of Colorado, the story repeats: climate is not merely a stage for human history, but a powerful actor. Megadroughts demonstrate how fragile even complex societies can be when the fundamental geographic and environmental pillars they are built on—reliable rainfall and fertile soil—are removed.

These stories from the past serve as a profound warning for our present. Today, the American West is in the grip of its own megadrought, the worst in over 1,200 years, exacerbated by human-caused climate change. We see the strain on our own water systems, agriculture, and cities. The Akkadians, Maya, and Ancestral Puebloans couldn’t see the climatic shifts coming. We can. The evidence of their collapse is a lesson written across the globe, urging us to build a more resilient future before our own thriving centers become the silent ruins of tomorrow.