Monuments of Stone, Landscapes of Meaning

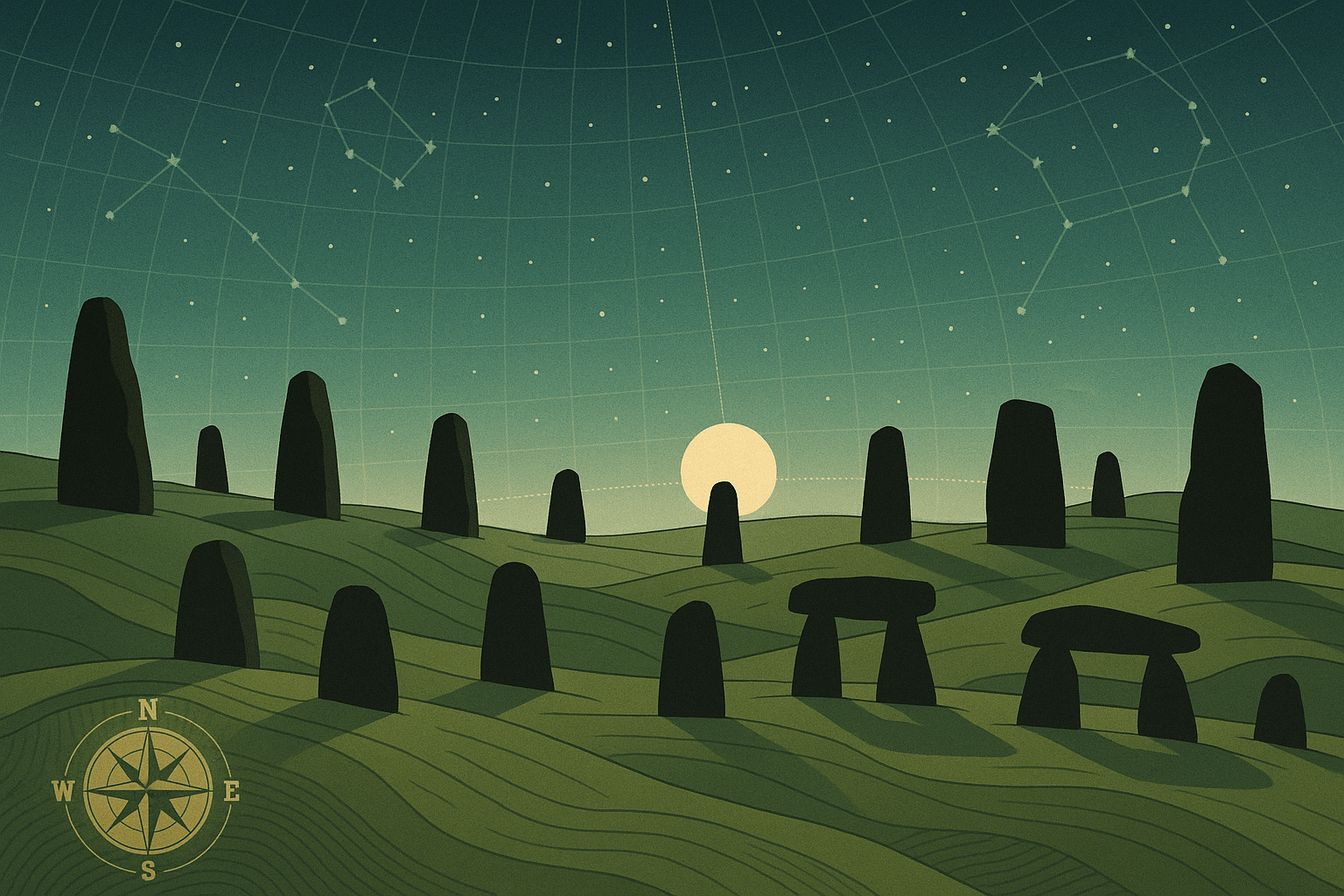

The term “megalith” comes from the Greek mégas (great) and líthos (stone). These structures are defined by their use of massive, often unhewn or roughly dressed stones, and they appear in several distinct forms:

- Menhirs: Single upright standing stones, sometimes found alone, sometimes in groups.

- Dolmens (or Portal Tombs): Three or more upright stones supporting a large flat capstone, creating a chamber often used for burials.

- Alignments: Multiple rows of menhirs stretching for considerable distances.

- Stone Circles: Stones arranged in a circular or elliptical pattern.

Crucially, these stones were rarely placed in isolation. They were integrated into the topography, often positioned on ridges, in valleys, or near water sources. They transformed a natural space into a human-centric place. This wasn’t just construction; it was an act of large-scale geographical design, a dialogue between people and their environment.

Mapping the Megaliths: A Coastal Phenomenon

The distribution of megalithic sites is one of their most fascinating geographical features. The vast majority are found along the Atlantic fringe of Europe—a sweeping arc from Portugal and Spain, up through Brittany in France, across the British Isles, and into southern Scandinavia. This distinct coastal pattern strongly suggests that the ideas, and perhaps the people, behind megalithic construction traveled along ancient sea routes. The ocean, far from being a barrier, was a highway for cultural exchange.

Nowhere is the sheer scale of this phenomenon more apparent than at the Carnac alignments in Brittany, France. Here, over 3,000 prehistoric standing stones are arranged in long, parallel rows that stretch for more than four kilometers across the landscape. The three major groups of alignments—Le Ménec, Kermario, and Kerlescan—form a monumental complex that would have required immense social organization and a shared, multi-generational purpose to complete. The builders of Carnac didn’t just place stones; they sculpted the geography of the entire region, creating a ritual pathway of a size and scope that is hard to comprehend even today.

Reading the Sky: Alignments of Sun and Moon

If the spatial distribution of megaliths tells a story of human geography and movement, their specific orientations reveal a deep connection to the cosmos. Many of these sites are sophisticated astronomical observatories, precisely aligned to mark significant celestial events. This field of study, known as archaeoastronomy, has shown that these early societies possessed a profound knowledge of the sun’s and moon’s cycles.

The most famous example, of course, is Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in England. Its layout is a masterclass in celestial alignment. On the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, the rising sun appears directly over the outlying Heel Stone when viewed from the center of the circle. Conversely, on the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, the setting sun aligns perfectly with the principal axis of the monument, framed by the great trilithon. These alignments were not accidental; they marked the crucial turning points of the agricultural year, providing a reliable calendar for planting and harvesting.

The geography of Stonehenge’s construction is equally staggering. The larger sarsen stones, weighing up to 30 tons, were quarried from the Marlborough Downs about 32 kilometers (20 miles) away. Even more remarkably, the smaller “bluestones” have been geologically traced to the Preseli Hills in Wales—a journey of over 240 kilometers (150 miles)! Hauling these multi-ton stones over land and possibly water represents an incredible investment of labor and resources, underscoring the immense importance of the site.

Why Did They Do It? Theories of Purpose

So, why did these ancient cultures pour such immense effort into arranging stones? There is likely no single answer, but rather a combination of powerful motivations that blend the practical with the spiritual.

- A Sacred Calendar: The astronomical alignments clearly indicate a need to track time and seasons. In an agricultural society, knowing when to sow and when to reap was a matter of life and death. The monuments were a reliable, permanent clock, hardwired into the landscape and the heavens.

- A Ritual Landscape: These were not merely scientific instruments. The sheer scale and processional nature of sites like Carnac and Stonehenge suggest they were vast outdoor temples. They were places for ceremonies, gatherings, and seasonal festivals that reinforced community bonds and a shared cosmology. The landscape itself became the sacred text.

- A Statement of Power and Permanence: Erecting a megalith is a profound statement. It claims a piece of land, demonstrating a community’s ability to marshal resources, organize labor, and alter their physical world. In a non-literate society, these monuments were a way of cementing identity, territory, and ancestral lineage onto the earth itself, creating a legacy for generations to come.

- A Connection to the Dead: Many megalithic sites are intrinsically linked to burial and ancestor veneration. The dolmens were tombs, and even Stonehenge is surrounded by hundreds of burial mounds. The stones may have acted as intermediaries between the world of the living and the realm of the ancestors, grounding a community’s place in the world through its connection to those who came before.

The megalithic landscapes of Europe are far more than a prehistoric mystery. They are the earliest surviving evidence of humanity’s drive to impose order on the world, to map their place within the cosmos, and to create meaning through the monumental transformation of their geography. They stand today as a testament to a time when the earth, the stones, and the sky were woven together into a single, sacred whole.