Imagine a geologist, centuries from now, drilling deep into the sediment of a dried-out river delta. As they pull the core sample to the surface, they see the expected layers of silt, sand, and clay, a timeline of floods and droughts written in earth. But then, they hit something different. A distinct, thin stratum, glinting with microscopic, unnaturally colorful fragments. It’s not a volcanic ash layer or the fossilized remnants of ancient life. It is the unmistakable signature of our time: a layer of plastic.

This is no longer a futuristic scenario. It’s a present-day reality. All over the world, microplastic pollution has become so pervasive and persistent that it is now forming a distinct, measurable, and tragically permanent marker in the Earth’s stratigraphy. We are creating a new geological layer, a tombstone for the throwaway culture of the Anthropocene.

The Earth’s Time Capsule: A Primer on Stratigraphy

To grasp the gravity of this, we first need to understand stratigraphy. This branch of geology is, in essence, Earth’s history book. It studies rock layers (strata) and the process of sedimentation to piece together the planet’s past. Geologists look for clear, globally identifiable markers within these layers to define geological epochs and boundaries.

Perhaps the most famous example is the K-Pg boundary, a thin band of clay rich in iridium found all over the world. This layer marks the mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, caused by a colossal asteroid impact. The iridium, rare on Earth but abundant in asteroids, became the indelible signature of that cataclysmic moment. These markers, known as Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Points (GSSPs) or “golden spikes”, are the definitive bookends of geological time.

Scientists today are arguing that humanity has created its own “golden spike”, and plastic is one of its primary components.

From Convenience to Contamination: The Genesis of a Plastic Layer

The story of our plastic layer begins not in the ground, but in our homes, cars, and closets. Microplastics are tiny plastic particles less than 5 millimeters in size. They enter the environment in two main ways:

- Primary microplastics: These are intentionally manufactured to be small, like the plastic pellets (nurdles) used as raw material for plastic products, or the now-banned microbeads once common in face scrubs and toothpaste.

- Secondary microplastics: These are the result of larger plastic items breaking down. The plastic bag caught in a tree, the bottle cap on the beach, the synthetic fibers shed from our polyester fleece jackets in the wash, and the particles worn from car tires on asphalt all fragment under the forces of sun, wind, and water, creating a constant shower of microscopic plastic.

This shower began in earnest after World War II, a period known as the “Great Acceleration”, when mass production of plastics exploded. From a mere 2 million tonnes in 1950, global plastic production has skyrocketed to nearly 400 million tonnes per year. Much of this has been designed for single use, creating an unprecedented waste problem.

Drilling into the Anthropocene: Evidence from the Sedimentary Record

This is where physical and human geography collide. The plastic we discard on land is relentlessly transported by the planet’s natural systems. Rain washes microplastics from city streets into storm drains, which flow into rivers. Rivers, the great arteries of our continents, act as conveyor belts, carrying this plastic sediment downstream.

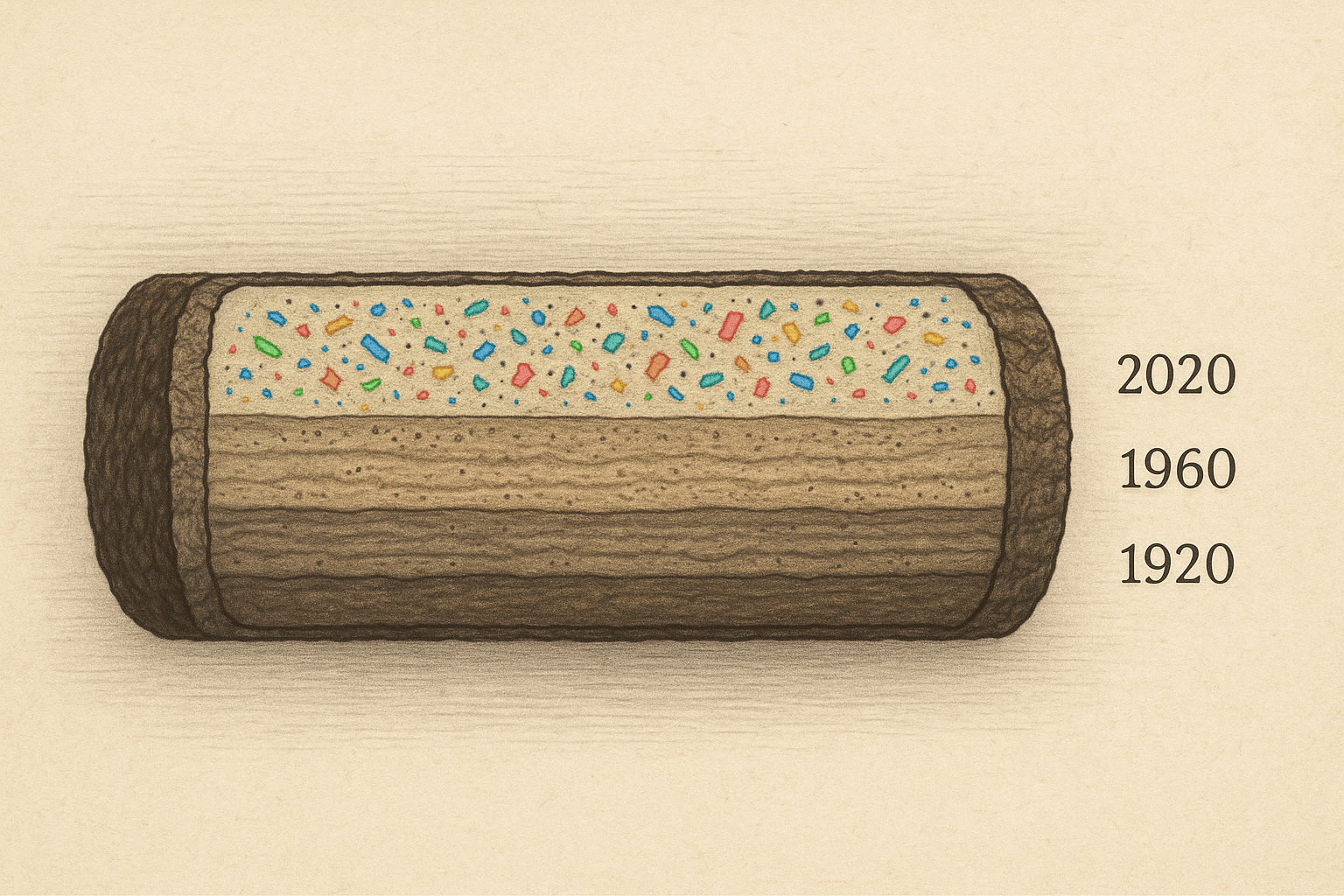

When the river’s current slows—in a lake, a delta, or upon reaching the ocean—the suspended particles, including microplastics, settle to the bottom. Year after year, new layers of sediment bury the old, locking our plastic waste into the geological record. Scientists are now drilling into this record and reading it like a book.

The findings are stark and globally consistent:

- California Coast, USA: In a landmark study of sediment cores from the Santa Barbara Basin, researchers found that the number of plastic particles began to increase exponentially from 1945 onwards. The layers perfectly mirrored the historical rise in global plastic production, doubling roughly every 15 years. The deepest, oldest layers were pristine; the newest are saturated with plastic.

- Crawford Lake, Canada: This small, deep lake near Toronto has been proposed as the “golden spike” location for the Anthropocene. Its sediments show a sharp, clear increase in microplastics and plutonium isotopes (from nuclear testing) beginning around 1950, creating a crystal-clear boundary line between the Holocene and our human-dominated epoch.

- The Baltic Sea, Europe: Sediment cores taken from the Baltic Sea show a clear timeline. The concentration of microplastics is negligible in layers deposited before 1950, but it skyrockets in the decades following, with polyester fibers from textiles and polyethylene fragments from packaging being the most common culprits.

- Deep-Sea Trenches: Even the most remote places on Earth are not safe. Microplastics have been found in the sediments of the Mariana Trench, nearly 11,000 meters below the surface. They are carried there by ocean currents and sinking organic matter, demonstrating the terrifyingly global reach of our pollution.

A Tragic Legacy: The Permanence of Plastic Fossils

Unlike organic matter, plastic does not biodegrade. It photodegrades, breaking into ever smaller pieces over hundreds or thousands of years. These particles are becoming what scientists call “technofossils”—human-made objects preserved in the rock record, as durable as the fossils of trilobites.

Future civilizations, or perhaps another species altogether, will find these technofossils compressed into new forms of rock. Scientists have already identified a new type of stone on Hawaiian beaches called “plastiglomerate”, a horrifying amalgam of melted plastic, volcanic rock, sand, and shells, fused together by beach campfires. It is, quite literally, a new rock of the Anthropocene.

This plastic layer is a global phenomenon. It is being laid down in the mud of the River Thames in London, the floor of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, the deltas of the Yangtze in China, and on the abyssal plains of every ocean. It is a unifying, democratic pollutant; it respects no borders.

What Our Geological Signature Says About Us

Geological layers tell a story. A layer of ash tells of a volcano. A layer of iridium tells of an asteroid. Our emerging plastic layer tells a story of a society so captivated by convenience that it contaminated its entire planet in the span of a single human lifetime.

It is a physical manifestation of a global economy built on disposability. It is a record of our consumption patterns, our technological choices, and our profound failure to manage our own creations. For future geologists studying the strata of the Earth, the Anthropocene will not be an abstract concept. It will be a visible, tangible, and colorful layer of plastic—an indelible scar marking the brief moment when a single species changed the very geology of its home.