The Slow, Steady Hand of Time: Understanding Uniformitarianism

To appreciate the revolution of neocatastrophism, we first have to understand the dogma it challenged. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, geologists like James Hutton and Charles Lyell championed the principle of uniformitarianism. Summarized by the famous phrase, “the present is the key to the past”, this theory states that the same gradual geological processes—erosion, sedimentation, volcanic activity—that we observe today have been operating at roughly the same rate throughout Earth’s history.

This was a radical idea. It replaced older, often religious, theories of catastrophism that invoked supernatural events (like a global flood) to explain Earth’s features. Uniformitarianism introduced the concept of “deep time”, the immense, almost unimaginable timescale necessary for a river to carve a Grand Canyon or for sediment to build a mountain range. For over a century, this slow-and-steady model was the bedrock of geology. Evidence that didn’t fit was often dismissed as heresy.

When the Earth Shakes: The Rise of Neocatastrophism

By the mid-20th century, however, a growing body of evidence simply couldn’t be explained by gradual processes alone. Geologists began to uncover landscapes that seemed to have been shaped by forces of unimaginable power and speed. Neocatastrophism was born not to replace uniformitarianism, but to amend it.

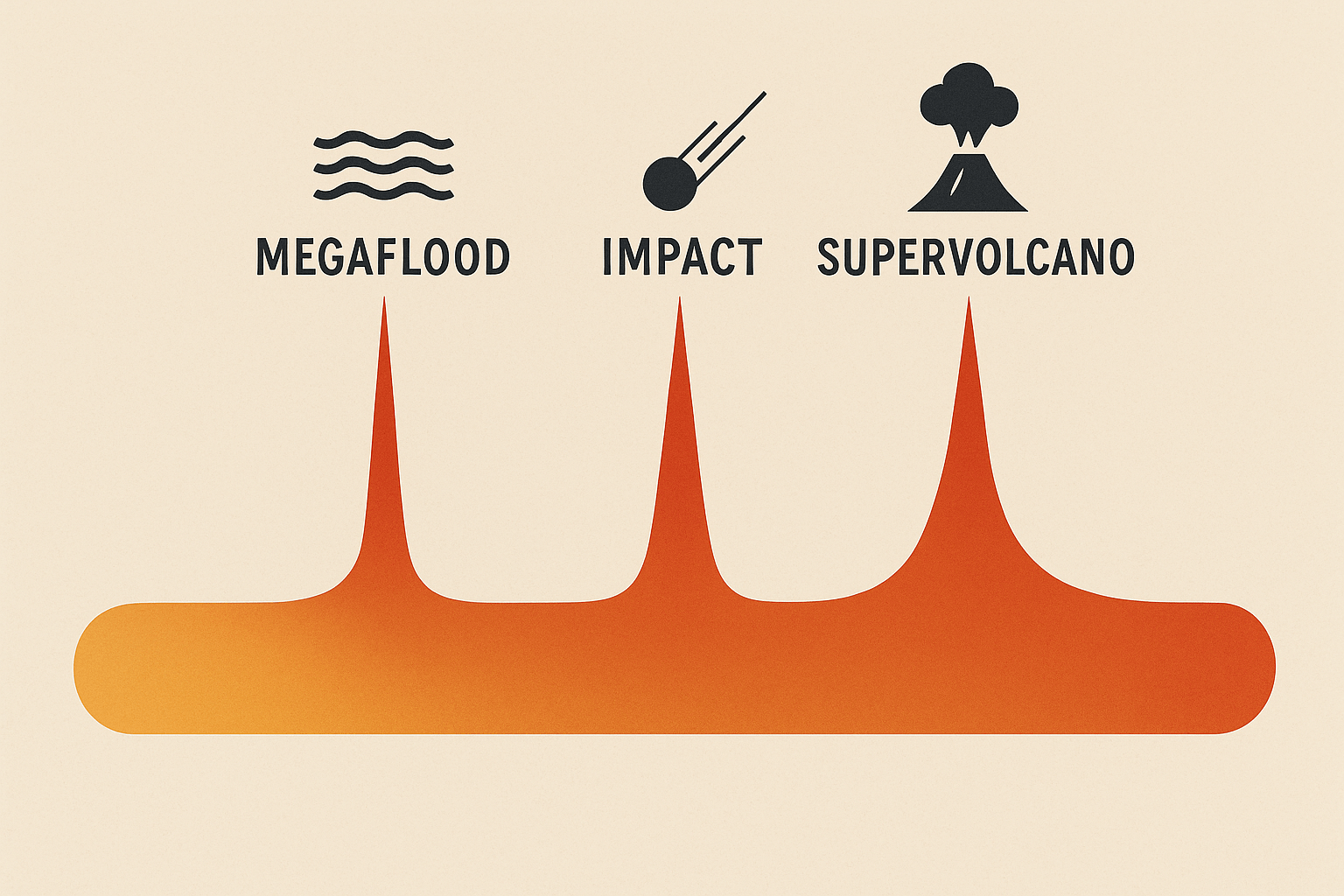

The modern theory accepts that gradual processes are the norm, shaping our world day in and day out. However, it also acknowledges that rare, high-magnitude, and short-duration events have a profound and sometimes dominant role in shaping the geologic record. The history of Earth, it argues, is one of long periods of calm punctuated by brief moments of geologic terror. Two types of events, in particular, provided the undeniable proof: megafloods and extraterrestrial impacts.

Case Study: The Channeled Scablands and a Geologic Heresy

Perhaps the most famous story of neocatastrophism is that of the Channeled Scablands in eastern Washington, USA. In the 1920s, geologist J Harlen Bretz surveyed this bizarre landscape. Instead of typical V-shaped river valleys, he found a chaotic network of immense, dry canyons (called coulees), giant potholes, 400-foot-high dry waterfalls, and gravel bars the size of hills. Most strikingly, he documented colossal ripple marks, up to 30 feet high, etched into the solid basalt bedrock.

Bretz proposed a hypothesis so outrageous it was met with ridicule: this entire landscape, covering thousands of square miles, was carved in a very short time by a single, colossal flood. His contemporaries, steeped in the doctrine of uniformitarianism, scoffed. There was no river in the world today that could create such features, and the idea smacked of the old biblical catastrophism they had worked so hard to discard.

For decades, Bretz was a geological outcast. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 60s, with the benefit of aerial photography and further research, that the source of his flood was found. Geologists discovered evidence of Glacial Lake Missoula, a massive prehistoric lake that formed in Montana behind a 2,000-foot-high ice dam. This dam failed repeatedly, unleashing cataclysmic floods with more than ten times the combined flow of all the rivers in the world today. These Missoula Floods roared across the landscape, ripping away soil and carving the Scablands into bare rock in a matter of days. Bretz was finally vindicated, and the Channeled Scablands became the poster child for neocatastrophism.

Looking to the Skies: Impact Craters as Landscape Architects

While megafloods reshaped regions, another type of catastrophe had a global reach: asteroid and comet impacts. For a long time, craters on Earth were often mistaken for ancient volcanoes. But the landmark discovery of the Chicxulub crater changed everything.

Buried beneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, the Chicxulub crater is a 110-mile-wide scar left by the impact of a six-mile-wide asteroid 66 million years ago. This wasn’t just a local event; it was a global catastrophe. The impact triggered mega-tsunamis, blasted superheated rock into the atmosphere causing worldwide wildfires, and kicked up so much dust and soot that it blocked out the sun, plunging the planet into a prolonged “impact winter.” This event is widely accepted as the cause of the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction, which wiped out about 75% of all species, including the non-avian dinosaurs.

On a smaller, more visible scale, there’s the Barringer Crater (or Meteor Crater) in Arizona. Formed just 50,000 years ago, this nearly mile-wide, 560-foot-deep bowl was created in seconds by the impact of an iron meteorite. It is a stunning visual reminder that landscapes can be created in an instant, not just worn down over eons.

A Balanced View: Gradualism and Catastrophe in Harmony

So, is the Earth’s story one of slow, patient change or violent, sudden upheaval? The answer, thanks to neocatastrophism, is both. The two concepts are not mutually exclusive; they are partners in shaping our world.

Think of it like this: the day-to-day life of a city is uniformitarianism—traffic flows, buildings age, parks are maintained. A major earthquake is a catastrophic event—in minutes, it can level buildings and reroute rivers, fundamentally altering the city’s landscape for centuries to come. Afterward, the slow, daily processes of rebuilding and erosion resume, but they are now operating on a completely new template.

The Colorado River continues its slow work of deepening the Grand Canyon. Wind and rain are gradually softening the sharp edges of the Barringer Crater. But the foundational architecture of these and many other landscapes was dictated by events that defy our everyday sense of time and scale.

Reading the Landscape Anew

Neocatastrophism has given us a more complete and dynamic story of our planet. It encourages us to look at a landscape and see not just the patient work of millennia, but also the potential ghosts of ancient deluges and cosmic collisions. It reminds us that our planet is not a static museum piece, but a geologically active body where the unimaginable can, and does, happen. The ground we stand on is a testament to both the patient artist and the violent sculptor, a story written in slow prose and punctuated with explosive exclamation points.