These trails are a showcase of Aotearoa New Zealand’s dramatic physical geography, but they are equally a testament to its human geography. They are a curated experience, designed from the ground up to be the perfect intersection of adventure, accessibility, conservation, and tourism.

The Geographical Canvas: A Land Forged by Fire and Ice

To understand the Great Walks, one must first appreciate the stage on which they are set. New Zealand’s geography is a story of violent creation. Straddling the boundary of the Pacific and Australian tectonic plates, the islands are in a constant state of geological flux, resulting in a landscape of dramatic extremes.

South Island: The Realm of the Southern Alps

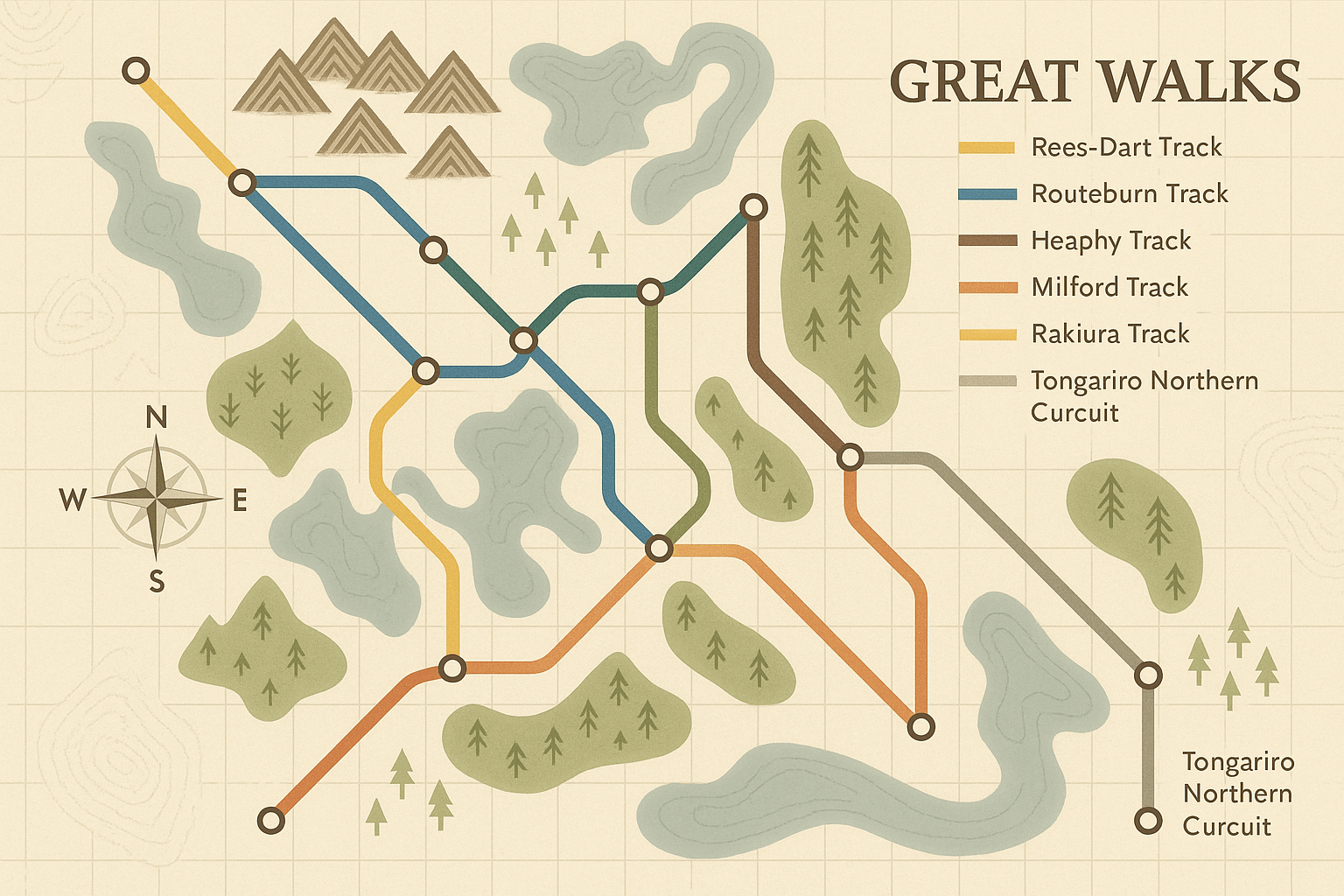

The South Island (Te Waipounamu) is dominated by the Southern Alps, a colossal mountain range pushed up by tectonic collision. During successive ice ages, massive glaciers scoured this landscape, carving deep U-shaped valleys and dramatic fiords. This is the heartland of the most famous Great Walks:

- The Milford, Routeburn, and Kepler Tracks: These three trails form a trifecta within Fiordland National Park. Hikers traverse high alpine passes, wander through lush temperate rainforests dripping with moss, and gaze upon waterfalls cascading down granite walls. The very existence of a walkable path here is an engineering marvel, as the terrain is naturally near-impassable.

- The Abel Tasman Coast Track: In contrast to Fiordland’s raw alpine drama, the Abel Tasman offers a gentler geography. Located at the top of the South Island, it follows a coastline of golden beaches, sculpted granite headlands, and turquoise waters. Its gentle gradients make it one of the most accessible Great Walks, a deliberate choice in curating a range of experiences.

North Island: Volcanoes and Ancient Rivers

The North Island (Te Ika-a-Māui) tells a different geological story, one dominated by the fire of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

- The Tongariro Alpine Crossing: This is arguably the most otherworldly Great Walk. It traverses a stark, active volcanic plateau in Tongariro National Park, a dual World Heritage site. The trail passes steaming vents, solidified lava flows, and the stunning, mineral-rich Emerald Lakes. Its geography feels Martian, a direct result of volcanic chemistry and power.

- The Whanganui Journey: Uniquely, this “Great Walk” is not a walk at all, but a canoe or kayak trip down the Whanganui River. The river has carved a deep path through the soft sedimentary rock of the central North Island, creating a landscape of forest-clad cliffs and tranquil waters. Its inclusion highlights a broader definition of “journeying” through a significant geographical and cultural landscape.

The Human Hand: Sculpting the Wilderness

A sublime landscape is only a canvas. The Great Walks as we know them are the result of decades of human intervention, transforming treacherous terrain into navigable, safe, and sustainable trails.

From Māori Pounamu Trails to Tourist Tracks

Many of these routes are not new. Long before European settlers arrived, Māori were traversing these formidable landscapes. The Routeburn Track, for instance, follows a traditional route used to trade pounamu (greenstone), a precious stone found on the South Island’s West Coast. The Whanganui River has profound spiritual significance for local iwi (tribes), who view it as an ancestor. Recognizing this human history is crucial; the “engineering” of the Great Walks built upon a foundation of ancient knowledge and use.

The Department of Conservation (DOC): The Grand Architects

The modern Great Walks system is the brainchild of New Zealand’s Department of Conservation (DOC). Faced with a dual mandate—to promote recreation and conserve natural heritage—DOC devised a system to manage the country’s most popular trails. This is where the engineering becomes most apparent.

Consider the infrastructure:

- Trail Construction: These are not simple dirt paths. Sections of track are meticulously built up with gravel to prevent erosion. Extensive boardwalks are constructed over fragile alpine wetlands and boggy forests. Sturdy swing bridges, capable of holding dozens of hikers, span rivers that would otherwise be dangerous, season-ending torrents. On the Milford Track, sections of the path were literally dynamited out of sheer rock faces in the early 20th century.

- The Hut System: The iconic backcountry hut is the cornerstone of the Great Walks experience. Strategically placed a day’s walk apart, these huts provide bunks, cooking facilities, heating, and toilets. This removes the need for hikers to carry tents and heavy cooking gear, dramatically increasing accessibility for those with less experience or physical capacity. It also concentrates human impact into small, manageable footprints.

- Intensive Management: DOC’s work is perpetual. Rangers maintain the huts, clear fallen trees, and repair track washouts. They manage complex booking systems that limit the number of hikers on a trail each day, preventing overcrowding and reducing environmental strain. An extensive network of traps for pests like stoats and possums protects the native birdlife that is so integral to the “Kiwi” wilderness experience. In avalanche-prone areas like the Routeburn and Milford, DOC staff actively monitor conditions and advise or even stop hikers from proceeding, adding a critical layer of safety.

A Curated Experience: The Perfectly Wild Product

The result of this intensive management is a highly curated, almost productized, version of wilderness. The Great Walks are a global tourism product, engineered for a consistent, high-quality experience.

This approach has clear benefits. It allows hundreds of thousands of people each year to safely access otherwise remote and dangerous environments. The fees generated from international visitors directly fund the conservation work that protects these special places. By funneling people onto hardened, well-maintained superhighways of the wilderness, DOC protects vast surrounding areas from uncontrolled human traffic.

However, this perfectly manicured wilderness isn’t without its critics. Some argue it dilutes the sense of true adventure and solitude. The competitive online booking system, which can sell out for a whole season in minutes, and differential pricing for international visitors, can feel exclusive. The very popularity it creates can lead to “Instagram queues” at photo spots, a far cry from the lonesome wild.

Ultimately, New Zealand’s Great Walks represent a brilliant, pragmatic compromise. They are an acknowledgment that in a world of growing tourism pressures, true wilderness cannot always be left to fend for itself. They are an engineered gateway, a carefully maintained window into the sublime power of New Zealand’s geography, offering a breathtaking wild experience, with a human-designed safety net conveniently attached.