Imagine a home that isn’t bound by a foundation, one that travels with you across vast landscapes, adapting to seasons and circumstances. This isn’t a modern fantasy from the “tiny home” movement, but an ancient reality. For millennia, nomadic peoples around the globe have perfected the art of mobile living, creating dwellings that are not just portable shelters but sophisticated pieces of engineering. Nomadic architecture is a profound expression of human geography, a testament to our ability to create homes that work in harmony with the physical geography of some of the world’s most challenging environments.

The Philosophy of a Mobile Home

Unlike sedentary architecture, which seeks to dominate and defy the environment, nomadic architecture is built on principles of cooperation and response. The core tenets are brilliant in their simplicity: lightness, durability, ease of assembly, and the use of locally-sourced, renewable materials. These homes are designed for a life dictated by the rhythm of the Earth—the seasonal search for pasture, the migration of animal herds, or the flow of trade routes. They are a direct answer to the questions posed by the land itself. This philosophy results in structures that are not only practical but also possess a deep, inherent sustainability that modern design is only now beginning to rediscover.

The Ger: Master of the Mongolian Steppe

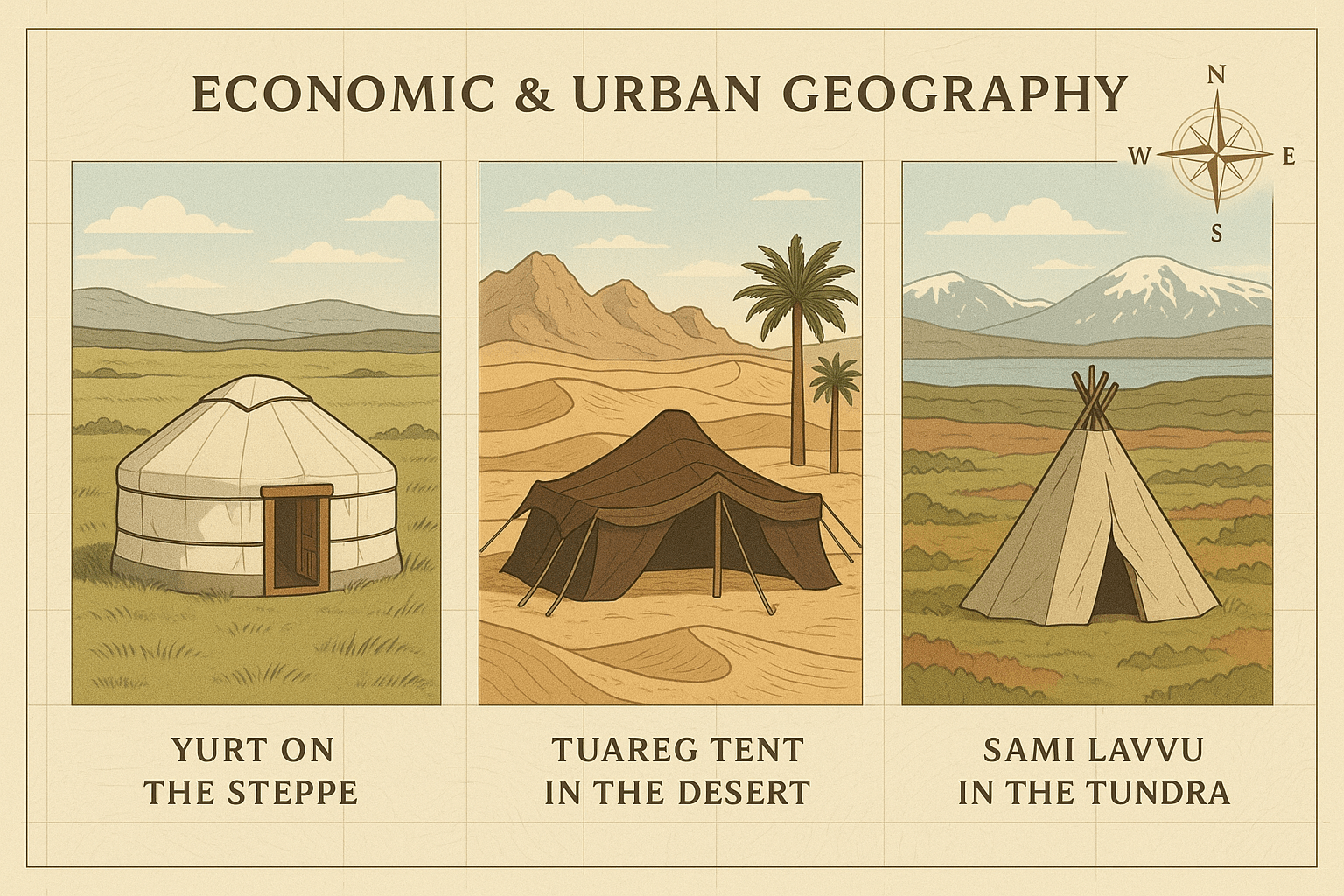

Nowhere is the genius of nomadic design more apparent than on the vast, windswept grasslands of the Mongolian-Manchurian steppe. Here, the physical geography presents a formidable challenge: scorching summers, brutally cold winters with temperatures dropping to -40°C, and relentless, gale-force winds. The answer to this environment is the Ger (known in Turkic languages as a Yurt).

The Ger is a marvel of aerodynamic and thermodynamic efficiency. Its key features include:

- Circular Shape: With no corners to catch the wind, the round form allows air to flow smoothly around it, making it incredibly stable in a landscape devoid of natural windbreaks.

- Lattice Framework: The collapsible wooden lattice wall (khana) provides structural integrity but can be folded down to a fraction of its size for transport. This is connected by roof poles (uni) to a central compression ring (toono). This design is strong enough to withstand heavy snow loads yet flexible enough to be packed onto a couple of camels or a small truck.

- Felt Insulation: The entire structure is wrapped in layers of felt (deever) made from the wool of the nomads’ own sheep. Felt is a phenomenal insulator, trapping warm air in the winter and keeping the interior cool in the summer. The number of felt layers can be adjusted based on the season, making the Ger a truly climate-responsive home.

- The Toono: The central ring at the apex of the roof is more than just a structural hub. It’s a skylight, a sundial for telling time, and a chimney, allowing smoke from the central stove to escape.

The human geography of the Mongols is imprinted on the Ger’s interior. The door always faces south, away from the harsh northern winter winds. The space is symbolically divided: the back is the most honored place, reserved for elders and altars; the west is the men’s domain, for storing hunting gear; and the east is the women’s, for cooking and utensils. The Ger is not just a shelter; it’s a microcosm of the Mongolian cosmos, moving with them across the steppe.

The Bayt al-Sha’ar: Shelter in the Shifting Sands

Travel from the cold steppe to the scorching heat of the Arabian and Saharan deserts, and you’ll find an equally ingenious solution: the Bedouin tent, or Bayt al-Sha’ar (“house of hair”). The geography here is defined by intense solar radiation, dramatic daily temperature swings, and the ever-present threat of sandstorms.

The Bedouin tent’s design is a masterclass in passive cooling and material science. It is traditionally woven from black goat hair, a choice that seems counterintuitive in a hot climate. Yet, the genius is in the weave.

- Breathable Weave: The dark, loosely woven fabric absorbs heat and creates temperature differences that generate convection currents. As hot air rises, it pulls cooler breezes through the open weave, creating ventilation. The dark color also provides excellent shade and cuts down on the blinding desert glare.

- Waterproof Transformation: During a rare desert downpour, the magic happens. The goat hair fibers swell with moisture, tightening the weave and making the fabric waterproof, shedding water away from the interior.

- Adaptable Structure: The tent is a long, rectangular structure with a low profile, held up by a series of poles and secured by long ropes. This design is incredibly adaptable. The walls are separate curtains that can be rolled up or down to control airflow, catch a breeze, or block wind-blown sand, depending on the conditions of the day.

Like the Ger, the tent reflects the human geography of its inhabitants. It is typically divided by a decorative curtain (qata) into a public section for men to receive guests—a cornerstone of Bedouin hospitality—and a private family section. Its portability is paramount for the pastoralist lifestyle, allowing families to follow scarce water and grazing resources across the desert.

Beyond the Steppe and Desert

Nomadic architecture is a global phenomenon. On the Great Plains of North America, the Tipi of the Indigenous peoples was a conical marvel. Its shape was perfect for shedding rain and snow, and a sophisticated system of adjustable smoke flaps at the top created a chimney effect, allowing for a central fire while keeping the interior smoke-free. Its design was intrinsically linked to the nomadic, bison-hunting culture of the Plains tribes.

In the wetlands of southern Iraq, the Marsh Arabs (Maʻdān) constructed their magnificent arched homes (Rifa or Mudhif) entirely from reeds harvested from their unique environment. While semi-nomadic, their architecture demonstrates the same principle: building with what the immediate geography provides, creating a structure perfectly suited to its place.

Lessons for a Modern World

In an era of climate change and resource scarcity, the ancient wisdom of nomadic architecture is more relevant than ever. These structures are models of sustainability, using local, biodegradable materials with a minimal carbon footprint. They are paragons of efficiency and minimalism, proving that a home needs to be smart, not necessarily large.

From disaster-relief shelters to the minimalist tiny-house movement and pre-fabricated modular homes, modern innovators are borrowing principles that nomads perfected centuries ago. These homes on the move teach us a powerful lesson: that the most enduring architecture is not that which stands in defiance of geography, but that which moves in dialogue with it, embodying a lighter, more intelligent, and more respectful way of living on our planet.