Ophiolites are one of plate tectonics’ most spectacular and perplexing creations. They are complete, intact sections of oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle that have been violently thrust up and stranded on top of continental land. These geological marvels are our only direct window into the processes that form two-thirds of our planet’s surface, offering a journey to the bottom of the sea without ever getting wet.

The Anatomy of an Ancient Ocean Floor

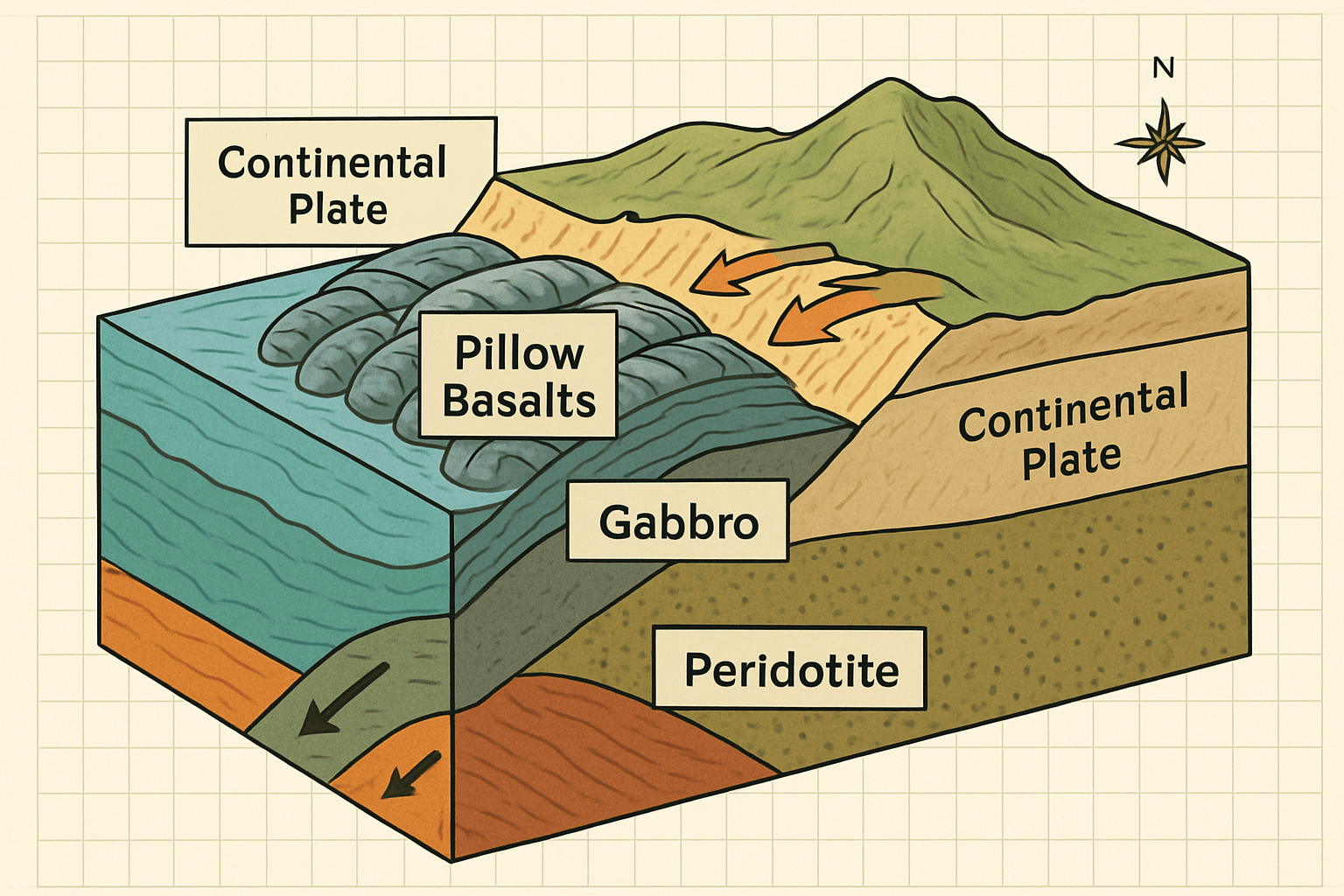

Finding a complete ophiolite is like finding a perfect fossil—it tells a complete story. Geologists have identified a distinct, layered sequence that represents a vertical slice through the oceanic lithosphere. From top to bottom, a classic ophiolite sequence includes:

- Deep-sea Sediments: The very top layer consists of fine-grained sedimentary rocks like chert and shale. These are the fossilized remains of microscopic marine organisms and fine clay that slowly settled onto the ocean floor over millions of years.

- Pillow Lavas: Below the sediments are the iconic pillow lavas. When basaltic magma erupts from volcanoes on the seafloor (at a mid-ocean ridge), the cold seawater rapidly quenches the lava’s surface, forming a glassy crust. Continued lava flow inflates this crust like a balloon, creating distinctive pillow-like shapes. Seeing these in a mountain range is definitive proof of an ancient marine environment.

- Sheeted Dikes: This is a fascinating and chaotic-looking layer. It’s a series of parallel, vertical intrusions of rock (dikes) that essentially fed the lava flows above. They represent the plumbing system of the mid-ocean ridge, where magma cracked its way to the surface.

- Gabbro: Further down, the magma that didn’t reach the surface cooled much more slowly, forming a coarse-grained crystalline rock called gabbro. This represents the “magma chamber” that fueled the entire system of crust formation.

- Peridotite: At the very bottom is peridotite, a dark, dense rock that is the primary component of the Earth’s upper mantle. This is the deepest material we can typically see on the surface, the rock upon which the oceanic crust was originally built.

How Do You Get an Ocean on a Mountain?

So, how does a massive, dense slab of oceanic crust end up on top of lighter continental crust? The usual story at a convergent plate boundary is subduction, where the denser oceanic plate dives beneath the continental plate and is recycled into the mantle. But sometimes, things go haywire.

The process that creates ophiolites is called obduction—a geological term for “shoved over the top.” While the exact mechanics are still debated, the general theory involves the closing of an ocean basin. As two continents approach each other, the oceanic crust caught between them gets squeezed. Instead of subducting cleanly, a slice of the oceanic plate is scraped off, buckled, and thrust—or obducted—up and onto the edge of the approaching continent. The collision is so immense that it preserves the entire crustal sequence, hoisting it miles into the air as mountain ranges form.

A Geologist’s Grand Tour: Where to Find Ophiolites

While fragments of ophiolites are found globally, a few locations stand out for their sheer scale, completeness, and importance to our understanding of the planet. These are bucket-list destinations for any earth science enthusiast.

The Semail Ophiolite, Oman and the UAE

This is the undisputed king of ophiolites. Spanning over 30,000 square miles across the mountains of Oman and the United Arab Emirates, the Semail Ophiolite is the largest, best-exposed, and most-studied ophiolite on Earth. Formed about 95 million years ago in the Tethys Ocean, it was thrust onto the Arabian continental plate. Driving through the Al Hajar Mountains, you are surrounded by its dark, imposing rocks, a stark contrast to the pale limestone it rests upon. The ophiolite isn’t just a scientific treasure; it’s a cornerstone of Oman’s economy, hosting rich deposits of chromite (a source of chromium) and copper.

The Troodos Ophiolite, Cyprus

The island of Cyprus owes its very existence—and its name—to an ophiolite. The Troodos Mountains in the center of the island are a beautifully preserved, uplifted section of ancient seafloor. This ophiolite is so integral to the island’s history that it’s believed the name “Cyprus” is derived from the classical Greek word for copper, Kypros, a metal that has been mined here for thousands of years from deposits within the ophiolite’s pillow lavas. Hiking through the Troodos Geopark, you can walk through the entire ophiolite sequence, from the mantle rocks on Mount Olympus to the pillow lavas in the surrounding valleys.

The Bay of Islands Ophiolite, Newfoundland, Canada

A designated UNESCO World Heritage Site, the landscape of Gros Morne National Park is dominated by this spectacular ophiolite complex. The most famous part is the “Tablelands”, a flat-topped, rust-colored mountain of peridotite from the Earth’s mantle. Because mantle rock is rich in heavy metals and lacks the usual nutrients for plant growth, the Tablelands are an eerie, barren landscape resembling a Martian desert. It provides one of the most accessible places on the planet where you can walk directly on the Earth’s mantle.

Why Ophiolites Matter

Ophiolites are far more than just geological curiosities. They are invaluable for several reasons:

- A Window into the Earth: We cannot drill deep enough to study a mid-ocean ridge’s structure directly. Ophiolites are our natural laboratories, allowing us to walk across and sample a complete cross-section of the oceanic crust and mantle.

- Economic Resources: The processes that form oceanic crust also concentrate valuable minerals. Ophiolites are major global sources of chromium, copper, nickel, platinum, and cobalt.

- Evidence for Plate Tectonics: The discovery and study of ophiolites in the 1960s was a critical piece of evidence that cemented the theory of plate tectonics. Their existence could only be explained by seafloor spreading and the dramatic collision of continents.

The next time you see a picture of a rugged, dark mountain range in a place like Oman or Cyprus, remember that you might be looking at an ancient ocean. Ophiolites are a profound reminder of the immense and relentless power of our planet—a power that can close oceans, build mountains, and place the bottom of the sea on the highest peaks.