Forget what you know about the humble potato. Move beyond the familiar russet, the golden Yukon, or the red-skinned varieties lining your supermarket aisle. To truly understand the potato, you must travel to its birthplace, a landscape of breathtaking altitude and ancestral wisdom: the Peruvian Andes. Here, nestled in the Sacred Valley near Cusco, lies a “living library” of potatoes, a vibrant, open-air archive that holds a genetic key to the future of global food security.

This isn’t a library of books and shelves, but of soil, sun, and stewardship. Known as the Parque de la Papa, or Potato Park, it is a biocultural sanctuary managed by the very people whose ancestors first domesticated this remarkable tuber over 7,000 years ago. It is a story of geography at its most dynamic, where physical landscapes and human culture have intertwined to create a bastion against climate change and blight.

The Cradle of the Potato: A Geographical Nexus

The story of the potato is inseparable from the geography of the Andes. This formidable mountain range, stretching along the western coast of South America, is not a uniform monolith. It is a complex tapestry of peaks, valleys, and high-altitude plateaus (the Altiplano) that create an astonishing diversity of microclimates. It is this geographical variety that served as the engine of potato evolution.

In the region surrounding the Potato Park, altitudes can soar from 3,400 to 4,900 meters (11,150 to 16,000 feet) above sea level. Within a single mountainside, you can experience a dramatic shift in environmental conditions:

- Temperature: Intense solar radiation during the day gives way to frigid, freezing nights.

- Soil: The soil composition changes with elevation and slope, from rich valley floors to thin, rocky soils higher up.

- Precipitation: Rainfall patterns can vary significantly over just a few kilometers.

For millennia, indigenous farmers have utilized this vertical landscape. By planting different potato varieties at different elevations, they harnessed these microclimates, allowing natural selection and careful human cultivation to coax out an incredible spectrum of traits. This is evolution in action, a geographical phenomenon that resulted in potatoes adapted to resist frost, drought, pests, and poor soil—a genetic treasure chest forged in the thin Andean air.

Inside the Parque de la Papa: A Living Collection

The Potato Park itself is a community-managed territory spanning over 9,000 hectares and governed by six indigenous Quechua communities. For them, the potato is not merely a crop; it is a cultural cornerstone, deeply woven into their cosmology, their ceremonies, and their connection to Pachamama (Mother Earth). These communities are the librarians, the curators, and the guardians of this priceless collection.

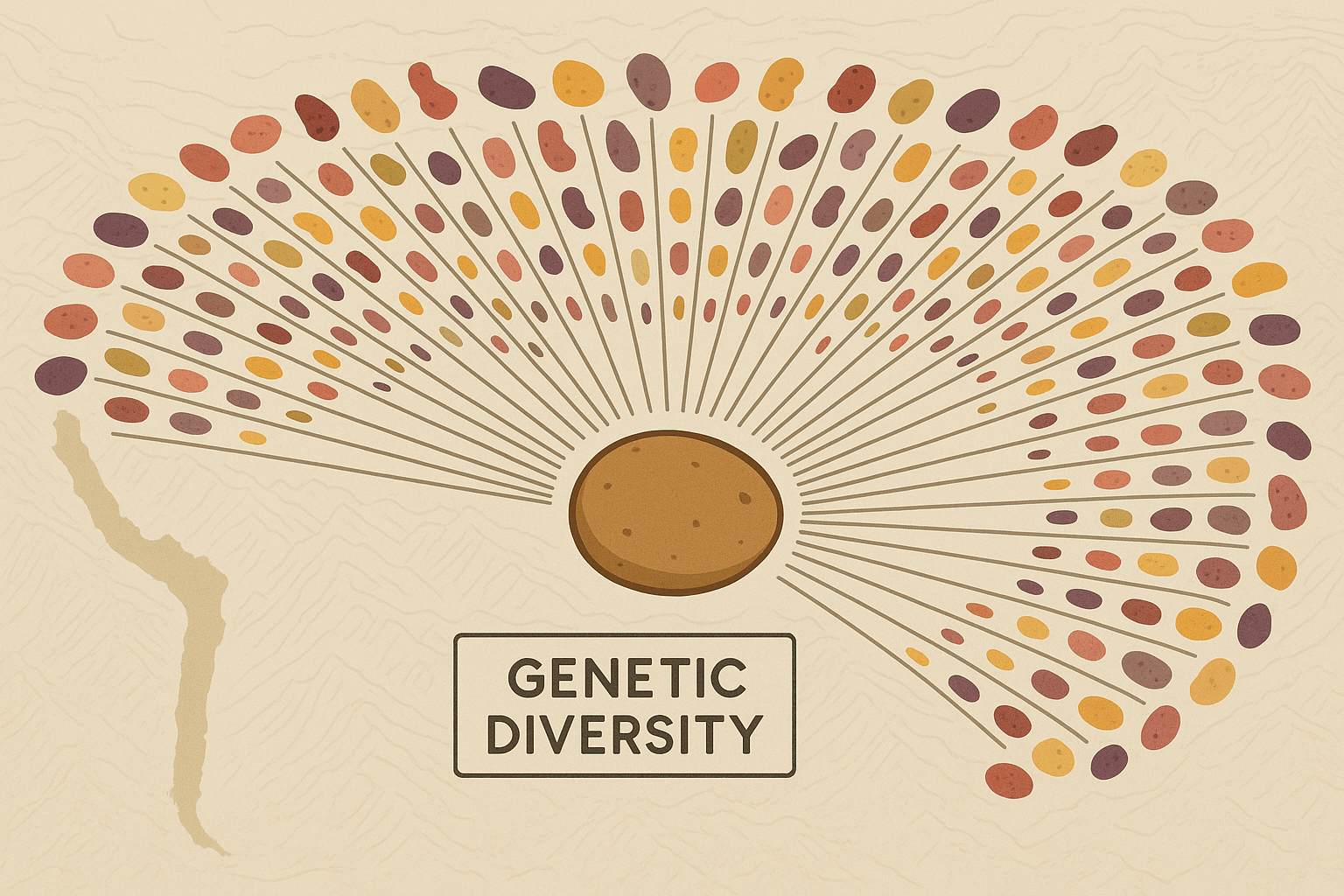

And what a collection it is. While the world’s commercial agriculture relies on a handful of potato types, the farmers of the Potato Park cultivate over 1,300 native varieties. They come in a riot of colors—deep purples, vibrant reds, mottled blues, and sunny yellows. Their shapes are just as varied, from smooth and round to gnarled, twisted, and finger-like. Each potato has a name, a story, and a purpose. Some are ideal for creating chuño, a naturally freeze-dried potato that can be stored for years, a crucial food source developed to survive the harsh Andean climate. Others are prized for their floury texture in soups, their waxy consistency for roasting, or even their use in natural dyes and medicines.

This immense diversity, scattered across countless small, terraced plots, is a direct expression of human geography. It showcases a system of knowledge passed down through generations—a system that understands the intimate relationship between a specific seed, a patch of soil, and a place on the mountain.

A Library Against Global Threats

The work happening in the Potato Park is more than just cultural preservation; it is a critical strategy for global resilience. In our modern world, we face two immense threats to our food supply: climate change and the danger of monoculture.

First, climate change is making its presence felt acutely in the Andes. Glaciers are receding, temperatures are rising, and weather patterns are becoming unpredictable. Pests and diseases that were once confined to lower, warmer elevations are now climbing higher, threatening potato plots that were previously safe. The Potato Park acts as a real-time laboratory for adaptation. As one variety struggles with new conditions, the farmers know that another, planted just up the slope, might possess the genetic resilience to thrive. The park’s diversity is its insurance policy.

Second, the Potato Park is the ultimate antidote to the peril of monoculture. The Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s serves as a stark geographical lesson: Ireland’s near-total reliance on a single potato variety, the “Lumper”, led to catastrophic crop failure and starvation when a blight swept through. Today, much of the world’s industrial agriculture still relies on a dangerously narrow genetic base. The Potato Park, along with the International Potato Center’s (CIP) gene bank in Lima which holds over 4,600 unique potato accessions, provides a global safety net. Scientists and breeders can turn to this genetic library to find traits—like drought resistance or immunity to new diseases—that can be bred into varieties grown in Africa, Asia, and beyond, securing food for millions.

A Model for a Sustainable Future

Perhaps the most profound lesson from Peru’s Potato Library is the power of biocultural conservation. It recognizes that biodiversity cannot be saved in a vacuum. It is inextricably linked to the people, the culture, and the knowledge systems that have nurtured it for centuries.

In a landmark agreement, the CIP repatriated hundreds of native potato varieties from its gene bank in Lima back to the communities of the Potato Park. The communities, in turn, act as custodians, planting and protecting these varieties in-situ—in their original geographical context. This partnership honors indigenous rights and ensures that the benefits of this genetic wealth, whether through ecotourism or the development of new products, flow back to the guardians themselves.

The next time you eat a potato, think of its journey. Its story begins not in a factory farm, but here, on a steep mountainside in Peru, where the geography of the high Andes and the wisdom of its people have created a living library—a vibrant, resilient, and essential resource for us all.