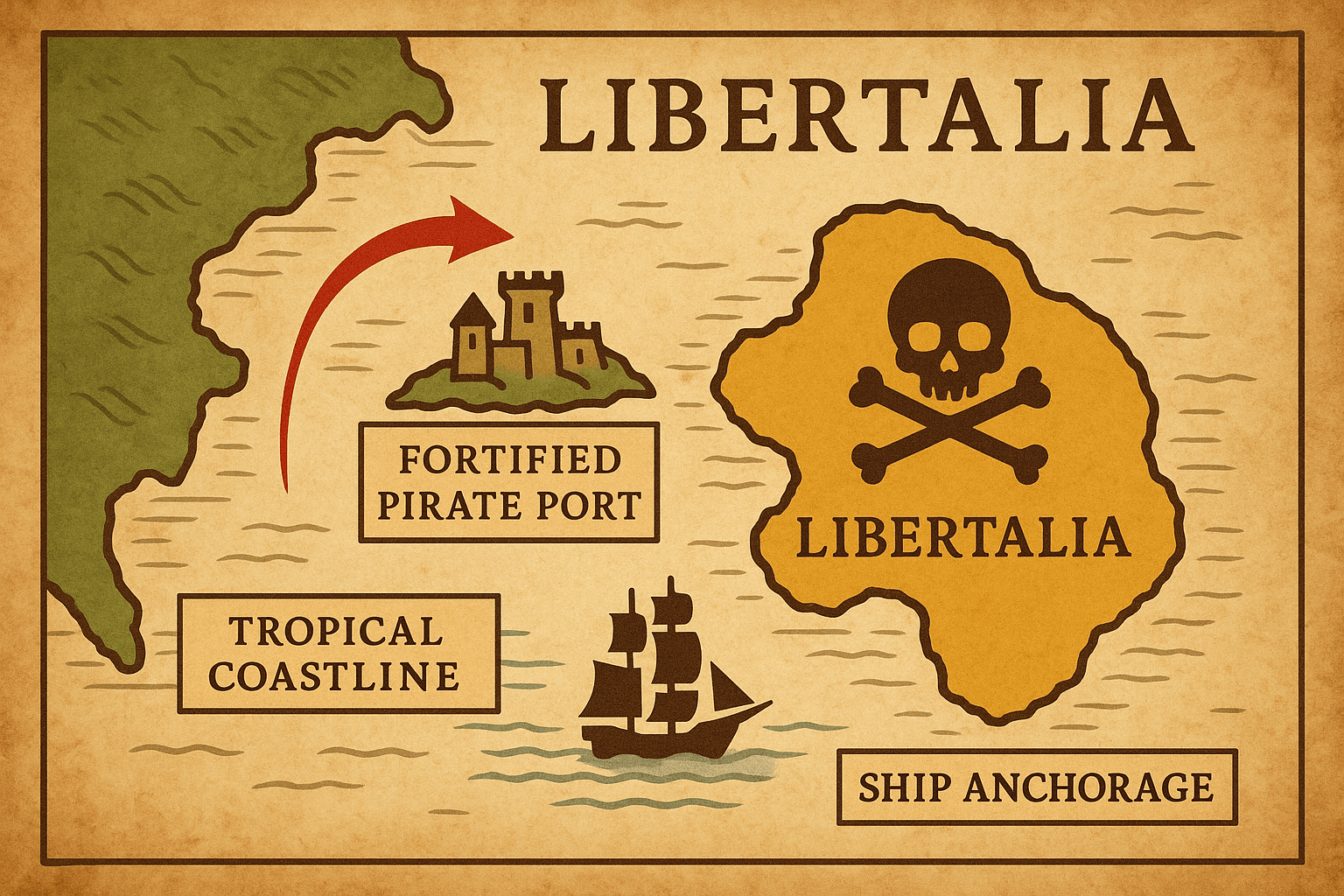

Forget treasure maps marked with a simple ‘X’. The real story of the Golden Age of Piracy is written not just in plunder and naval battles, but in the very geography of the world they navigated. For a brief, dazzling period at the turn of the 18th century, pirates didn’t just roam the seas; they built their own worlds. They created temporary autonomous zones—havens of liberty and lawlessness—on the fringes of empire. And no place better illustrates this phenomenon than the semi-mythical republic of Libertalia, supposedly founded on the shores of Madagascar.

While Libertalia itself may be a legend, a tantalizing tale from Captain Charles Johnson’s 1724 book, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, the geography that made such a dream possible was very real. Madagascar was, for a time, the world’s pirate capital. To understand why, we need to look at its unique position on the map and the very shape of its land.

The Geographic Canvas: Why Madagascar?

Location is everything, and for a pirate, Madagascar’s was perfect. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the island sat astride one of the most lucrative maritime highways on the planet. European powers like Britain, France, and the Netherlands had established fabulously wealthy trade routes through the Indian Ocean. Ships laden with silk, spices, porcelain, and jewels from India and the East Indies had to sail past Madagascar to get back to Europe. For pirates like Henry Avery, Thomas Tew, and William Kidd, this wasn’t an island; it was a strategically placed fortress from which to launch devastatingly effective raids.

But its strategic location was only part of the story. The physical geography of Madagascar itself made it an ideal sanctuary.

- A Pirate-Friendly Coastline: Madagascar’s coast is not a smooth, simple line. It is a jagged, indented landscape of deep bays, hidden coves, and barrier islands. The massive Bay of Antongil on the northeast coast, for instance, was large enough to shelter an entire fleet, protected from both violent weather and prying naval patrols.

- Natural Shipyards: Islands like Île Sainte-Marie (St. Mary’s Island) off the northeast coast became legendary pirate bases. Its sheltered harbors were perfect for careening—the essential process of beaching a ship to scrape barnacles and seaweed from its hull. Without careening, a ship’s speed would drop dramatically, making it useless for both pursuit and escape. Île Sainte-Marie offered the perfect secluded beaches for this vital maintenance.

- Abundant Resources: The island’s interior, with its dense rainforests and freshwater rivers, was a treasure chest of another kind. Pirates could easily restock on fresh water, hunt for food, and, most importantly, find timber to repair their battered ships. This self-sufficiency was crucial for operating thousands of miles from any friendly port.

–

–

The Human Geography of a Pirate State

If physical geography provided the stage, human geography wrote the script. During the Golden Age of Piracy, Madagascar was what geographers might call a liminal space—a threshold world, existing at the edge of established empires. While European powers had mapped its coast, they had no real administrative control over the island. It was a blank spot on the political map, a vacuum of state power that pirates were more than happy to fill.

Critically, Madagascar was not a unified nation. It was a complex patchwork of competing Malagasy kingdoms and clans. This political fragmentation was an opportunity. Cunning pirate captains could play one chief against another, forming alliances, trading stolen goods and firearms for fresh food and cattle, and even marrying into local communities. This created a unique hybrid society, a fusion of pirate and Malagasy cultures, that flourished for several decades. These weren’t just pirate outposts; they were integrated, if volatile, communities.

It was in this unique socio-geographic context that the idea of Libertalia could be born.

Libertalia: A Republic of the Map’s Edge

According to the legend, Libertalia was founded by Captain James Misson, a revolutionary French pirate. It was to be a new kind of society, a true pirate utopia. Its laws, known as Articles, supposedly abolished slavery (despite many real pirates being active slave traders), established universal male suffrage, and placed all treasure into a common fund. They even created their own international language, a mix of French, English, Dutch, and Malagasy.

Libertalia was, in essence, an attempt to create new spatial rules. In the world of empires, space was defined by kings, borders, and national laws. In Libertalia, space was to be defined by a pirate code of radical equality and shared ownership. It was a rejection of the world map and an attempt to draw a new one, however small, based on different principles.

Whether a single Libertalia ever existed is doubtful. It may have been a propagandistic fiction designed to romanticize piracy or a political satire. But what is certain is that the *phenomenon* it represented was real. For nearly 30 years, pirates established settlements on Île Sainte-Marie and along the coast, creating their own small-scale societies that operated on their own terms. Today, a pirate cemetery on Île Sainte-Marie serves as a haunting physical reminder of this strange chapter in history, its weathered, skull-and-crossbones-carved headstones marking the graves of men who lived and died in this pirate space.

The End of an Era

Why did this pirate world fade away? The geography that nurtured it eventually contributed to its demise. The European powers, tired of the constant disruption to their trade, began sending powerful Royal Navy squadrons to hunt the pirates down. The very coves that had offered sanctuary now became potential traps.

Simultaneously, the internal human geography of Madagascar shifted. A powerful Betsimisaraka leader, Ratsimilaho—who was, according to some legends, the son of an English pirate and a Malagasy princess—began unifying the coastal tribes. This new, centralized power was far less tolerant of the disruptive pirate presence, closing the political vacuum they had once exploited.

The pirate havens of Madagascar were ultimately temporary. But their story is a powerful lesson in geography. It shows how physical landscapes and human political structures can intersect to create unique, fleeting worlds. Libertalia may be a myth, but the geographic reality of Madagascar allowed thousands of outlaws to build something astonishing: a functioning, autonomous pirate society at the known world’s edge.