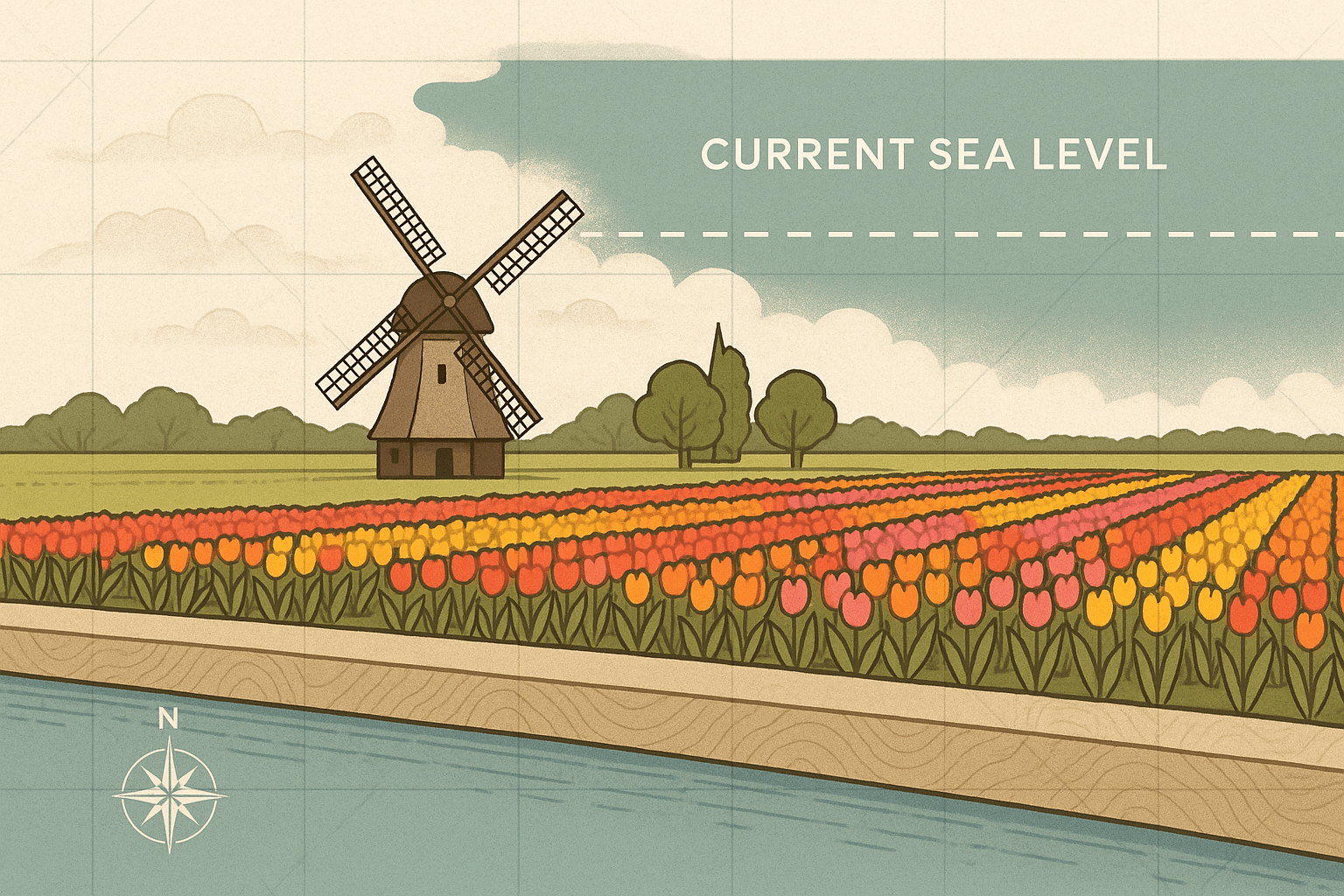

There’s an old saying that encapsulates the spirit of the Netherlands: “God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands.” This isn’t just a boastful quip; it’s a geographical reality. Drive through large parts of this densely populated European nation, and you might notice something peculiar. The water in the canals alongside the road is often higher than the fields and towns you’re driving through. Welcome to the world of polders, a landscape born from a centuries-long battle between human ingenuity and the unforgiving North Sea.

A staggering one-third of the Netherlands lies below sea level, with the lowest point dipping to nearly seven meters (23 feet) below. This incredible feat was made possible by one of the most ambitious and sustained geographical engineering projects in human history: the creation of polders. A polder is a low-lying tract of land reclaimed from a body of water—be it a lake, a river delta, or the sea itself—and protected by embankments known as dikes.

A Nation Forged by Water

To understand why the Dutch needed to create their own land, you have to look at their physical geography. The Netherlands is essentially the sprawling, low-elevation delta of several major European rivers, including the Rhine, Meuse, and Scheldt. For centuries, this meant living on marshy, unstable ground, perpetually threatened by river floods and storm surges from the North Sea. The history of the country is punctuated by catastrophic floods that reshaped the coastline and claimed tens of thousands of lives.

The initial drive for land reclamation, beginning as early as the 11th century, wasn’t just about creating living space. It was about survival and sustenance. Early communities began by building earthen mounds, called terpen, to keep their homes and churches dry. Soon, they moved on to draining peat bogs and smaller lakes to create incredibly fertile farmland. This was the genesis of the polder.

The Engineering of a Polder: A Step-by-Step Guide

Creating a polder is a multi-stage process that has been refined over centuries, evolving from manual labor and wind power to modern, computer-controlled systems. The basic principles, however, remain the same.

- Step 1: Enclosure with Dikes. The first and most critical step is to build a strong, continuous dike around the entire body of water designated for reclamation. This ring dike serves as the primary defense, a formidable barrier separating the future land from the surrounding water.

- Step 2: Pumping the Water Out. Once the area is enclosed, the water inside needs to be removed. This is where the iconic Dutch windmill enters the story. From the 15th century onwards, windmills were harnessed to power water wheels or Archimedes’ screws, which lifted water out of the enclosed area and deposited it into a network of canals on the other side of the dike. Often, a series of windmills—a molengang—was needed, with each one lifting the water a little higher until it could be discharged into a main drainage canal.

- Step 3: Preparing the Land. The newly drained land, known as sea clay or peat, is far from ready for use. It’s a soggy, saline mess. An intricate grid of smaller ditches and canals is dug to help the soil dry out and manage the water table. Over months and years, rainwater leaches the salt from the topsoil, slowly making it suitable for agriculture.

This process highlights a crucial reality of polder life: the work is never done. Because the reclaimed peat and clay compact and sink over time (a process called subsidence), the polder surface drops further below the surrounding water level. This means the pumps—which have since evolved from windmills to steam engines and now to powerful, automated electric pumping stations—must run continuously to prevent the land from reverting to a lake. To manage this perpetual task, the Dutch developed unique, local governmental bodies called waterschappen, or water boards, some of which have been in continuous operation for over 700 years.

From a Small Lake to an Entire Province

While thousands of small polders dot the Dutch landscape, a few monumental projects stand out.

The Beemster Polder (1612)

One of the earliest major successes, the Beemster was once a large lake north of Amsterdam. Drained in the early 17th century using more than 40 windmills, it was a project funded by wealthy merchants. Its design reflects the rational mindset of the Dutch Golden Age. The land was laid out in a perfect, rigid geometric grid of squares and rectangles, a pattern still clearly visible from the air today. For its well-preserved, rational landscape, the Beemster Polder is now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Zuiderzee Works

The most audacious project of all was the taming of the Zuiderzee (“Southern Sea”), a large, shallow, and destructive inlet of the North Sea. Following a devastating flood in 1916, the Dutch parliament approved a plan to seal it off from the sea. The key elements were:

- The Afsluitdijk (1932): A colossal 32-kilometer (20-mile) dike built right across the open sea. This dam transformed the saltwater Zuiderzee into a freshwater lake, the IJsselmeer.

- The Polders: With the threat of the sea removed, vast sections of the newly formed IJsselmeer were systematically diked and drained. This created the Noordoostpolder and, most remarkably, the Flevopolder.

The Flevopolder is the largest artificial island in the world, home to the Netherlands’ 12th province, Flevoland. Cities like Lelystad and Almere were built from scratch on this seabed, designed to alleviate population pressure from the nearby Randstad metropolitan area. Flevoland is the ultimate expression of the Dutch mantra: a whole province, complete with cities, farms, and nature reserves, existing where there was once only water.

The Polder Landscape Today

Today, the polder landscape is an integral part of Dutch identity. It’s a managed, artificial environment defined by its flatness, geometric precision, and the constant presence of water in canals and ditches. But it’s also a landscape under pressure. The ongoing soil subsidence and rising global sea levels due to climate change pose an existential threat.

Yet, the Dutch are not standing still. The same spirit of innovation that created the polders is now being applied to climate adaptation. Massive projects like the Delta Works—a series of dams, sluices, and storm surge barriers in the southwest—are considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World. The Dutch continue to reinvent their relationship with water, exploring concepts like floating homes and “Room for the River” programs that strategically allow controlled flooding to reduce pressure elsewhere.

The polder is more than just reclaimed land; it’s a living monument to foresight, engineering, and the profound geographical truth that for the Dutch, the struggle with water is not a battle to be won, but a dynamic relationship to be managed for generations to come.