In the aftermath of World War II, a quiet explosion began to ripple across the developed world. It wasn’t a weapon, but a sound: the cry of a newborn. And then another, and another, and millions more. This was the Baby Boom, a demographic shockwave so powerful it didn’t just swell populations; it fundamentally redrew the maps of our nations, creating new landscapes, economies, and social challenges that we are still navigating today.

From Foxholes to Front Yards: The Great Suburban Migration

At its core, the post-war baby boom (roughly 1946-1964) was a response to a period of unprecedented global upheaval. Soldiers returned home, couples reunited, and a sense of optimism, combined with economic prosperity, created the perfect conditions for starting families. In the United States alone, 76 million babies were born during this period. But where would they all live?

The cities of the early 20th century, crowded and dominated by aging tenement housing, were not the dream. The dream was space, a patch of green, and a home of one’s own. This collective aspiration, fueled by government-backed mortgages like the G.I. Bill, gave birth to a defining geographical phenomenon of the 20th century: the suburb.

The most iconic example is Levittown, New York. Developer William Levitt applied assembly-line techniques to home construction, erecting thousands of nearly identical, affordable single-family houses on former potato fields. This model was replicated across the continent. Vast tracts of farmland and wilderness on the peripheries of major cities were rapidly transformed into sprawling networks of cul-de-sacs, manicured lawns, and single-family homes. This mass exodus from the urban core led to what geographers call “hollowing out”, as cities lost tax base and population, while the suburbs swelled.

The car was the lifeblood of this new geography. The single-family home was inextricably linked to the two-car garage. Interstate highways, like the US Interstate Highway System initiated in 1956, became the arteries connecting these residential pods to urban job centers, cementing a car-dependent culture that dictates urban planning to this day.

Mapping New Markets: The Birth of Consumer Landscapes

This new suburban geography required a new economic geography to support it. The traditional downtown shopping district, with its department stores and small shops, was no longer convenient for the suburbanite. The solution was a revolutionary concept: the shopping mall.

Architect Victor Gruen’s Southdale Center in Minnesota, which opened in 1956, is often cited as the first fully enclosed, climate-controlled shopping mall. It was designed as a new “downtown” for the suburbs—a one-stop destination for shopping, dining, and socializing, all surrounded by a sea of parking. Malls sprung up across America, Australia, and Canada, becoming the commercial and social hearts of these new communities. This radically altered retail geography, pulling economic gravity away from city centers and towards the suburban fringe.

The boom also created massive new consumer markets targeted directly at these new families. The demand for baby products, from diapers to Dr. Spock’s parenting books, skyrocketed. As these children grew, so did the markets for toys (think Mattel and Hasbro), televisions (bringing shared culture into individual homes), and station wagons to haul the family and its goods.

A Global Phenomenon with Local Flavor

While the American experience is the most famous, the baby boom was not a purely US phenomenon. Many Allied nations experienced a similar demographic surge, though the timing and geographical expression varied.

- Canada and Australia: As nations of immigrants with vast open spaces, their booms were amplified by high birth rates and pro-immigration policies. This fueled the expansion of suburbs around cities like Toronto, Vancouver, and Sydney, mirroring the American model.

- Western Europe: In countries like the United Kingdom and France, the boom was also pronounced. France refers to the era as the Trente Glorieuses (“Thirty Glorious Years”) of economic prosperity and high fertility. However, with less available land and different planning traditions, suburban development often took the form of denser satellite towns or large apartment blocks on the urban periphery rather than the sprawling single-home model.

- Delayed and Muted Booms: The story was different in the defeated Axis powers. West Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder (“economic miracle”) led to a “delayed” boom that peaked in the mid-1960s. Japan experienced a very short, sharp boom from 1947-1949 before its birth rate declined rapidly.

The Long Echo: The Boomers’ Final Geographical Reshaping

Today, the Baby Boomers are entering their senior years, and their generation’s immense size is once again exerting a powerful gravitational pull on our geography, particularly in three key areas.

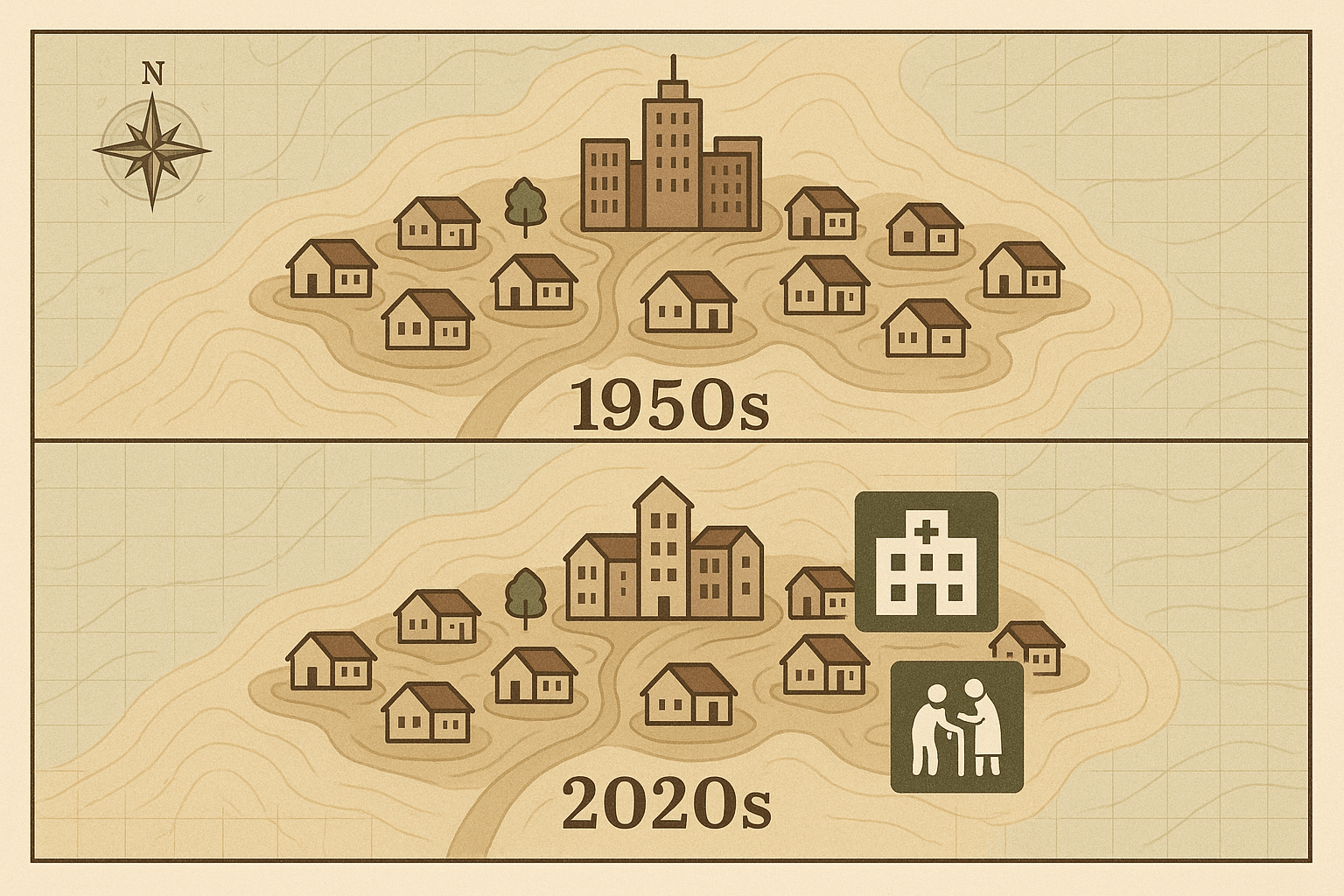

1. The Graying of the Suburbs

The very suburbs built for young families are now becoming vast, naturally occurring retirement communities. Many Boomers are “aging in place” in homes designed for a different stage of life. This creates a significant geographical challenge. These car-dependent landscapes are often ill-suited for seniors with declining mobility, located far from the concentrated medical services typically found in denser urban areas.

2. The Strain on Healthcare Geography

An aging population of this magnitude places an unprecedented strain on healthcare systems. The demand for hospitals, specialized clinics, and long-term care facilities is surging. The geographical question is critical: is the healthcare infrastructure located where the aging population lives? In many cases, there is a mismatch between the sprawling, low-density suburbs where Boomers reside and the centralized location of healthcare infrastructure, creating critical gaps in access.

3. The Great Retirement Migration

Not all Boomers are aging in place. Many are undertaking one last great migration. In the US, this has fueled the explosive growth of the “Sun Belt.” States like Florida, Arizona, North Carolina, and Texas have seen their populations swell with retirees seeking warmer climates and lower costs of living. This has transformed the demographic and political maps of these states, creating new retirement-focused cities and placing immense pressure on local water, infrastructure, and healthcare resources.

The story of the post-war baby boom is a lesson in how demography is destiny, written directly onto the physical landscape. It was a force that leveled fields to build subdivisions, created the shopping mall, and stretched our cities into vast metropolises. Now, as the generation that defined the 20th century enters its twilight, its legacy continues to shape our world, presenting a new set of geographical puzzles for the 21st century to solve.